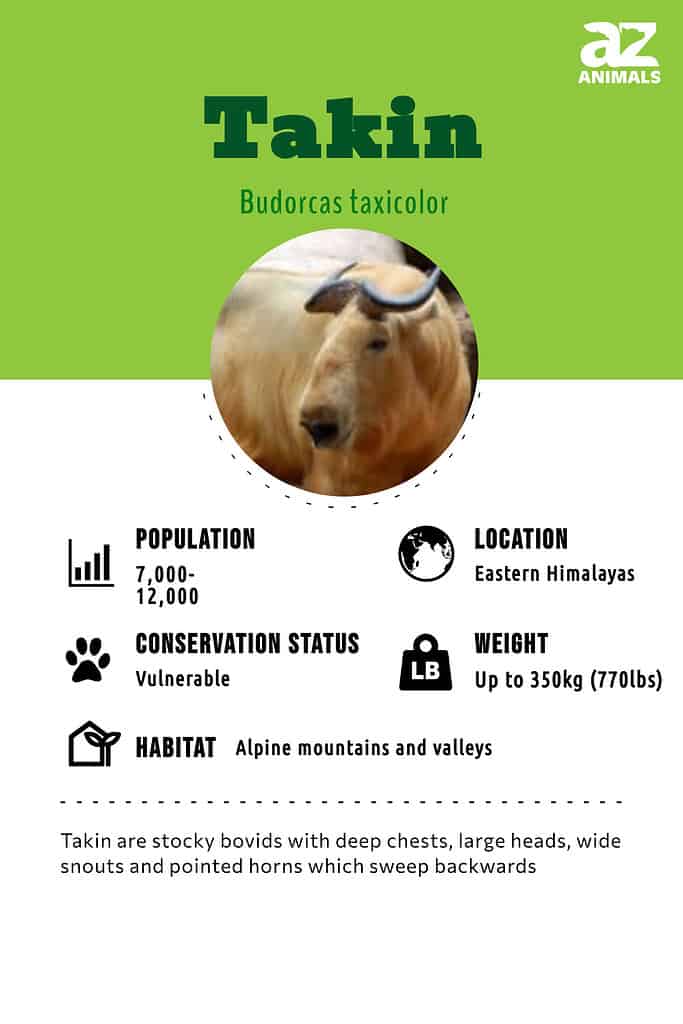

Takin

Budorcas taxicolor

The takin can leap some 6 feet through the air

Advertisement

Takin Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Mammalia

- Order

- Artiodactyla

- Family

- Bovidae

- Genus

- Budorcas

- Scientific Name

- Budorcas taxicolor

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Takin Conservation Status

Takin Facts

- Name Of Young

- Calves

- Group Behavior

- Herd

- Fun Fact

- The takin can leap some 6 feet through the air

- Estimated Population Size

- 7,000-12,000

- Biggest Threat

- Habitat loss and hunting

- Most Distinctive Feature

- The curved horns and shaggy coat

- Other Name(s)

- Cattle chamois and gnu goat

- Gestation Period

- 7–8 months

- Litter Size

- 1 (rarely 2)

- Habitat

- Alpine mountains and valleys

- Predators

- Wolves, leopards, dholes, and bears

- Diet

- Herbivore

- Favorite Food

- Leaves, grasses, herbs, and twigs

- Type

- Hoofed Mammal

- Common Name

- Takin

- Number Of Species

- 1

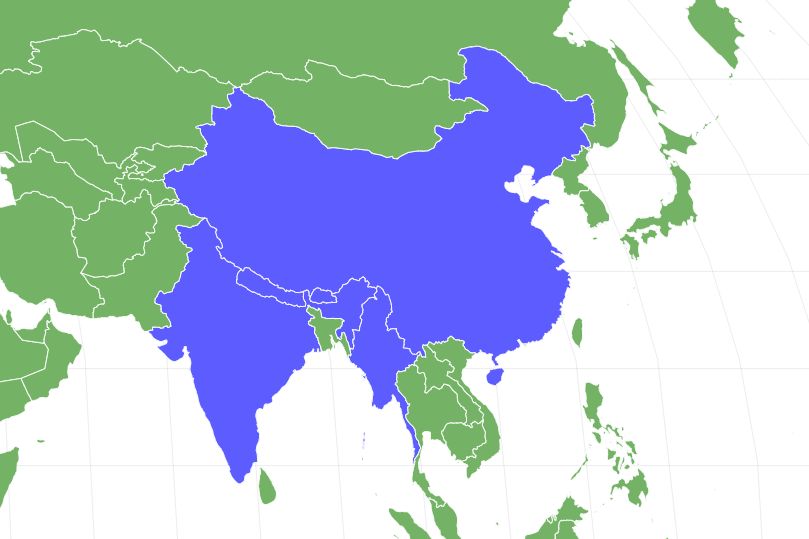

- Location

- Eastern Himalayas

Takin Physical Characteristics

- Color

- Brown

- Grey

- Yellow

- Black

- White

- Gold

- Skin Type

- Hair

- Lifespan

- Up to 20 years

- Weight

- Up to 350kg (770lbs)

- Height

- 1-1.14m (3.3-4.5ft)

- Length

- 1.5-2.2m (5-7.3ft)

- Age of Sexual Maturity

- 30 months

- Age of Weaning

- 1-2 months

The takin, also known as the cattle chamois or the gnu goat, looks like a cross between a cow, an antelope, and a goat.

But don’t be fooled by its strange appearance. This species is supremely well adapted for some of the most rugged terrains on the planet. It actually shares a close ancestry with goats and sheep, which are equally as talented at traversing difficult terrain. While numbers are currently on the decline from human activity, the takin is considered to be a national treasure in some parts of China. This article will cover many interesting facts about its appearance, behavior, and habitat.

4 Incredible Takin Facts!

- One of the most interesting facts about the takin is the way that it manages to stay warm in the frigid mountain environments. The large snout has a complex network of sinus cavities to warm up the air before it reaches the lungs. They also grow a thick secondary coat for the winter and shed it for the summer.

- Adult males are called bulls, adult females are called cows, and young baby takins are called calves.

- The oily substance secreted by their skin protects them from the rain and fog. It also allows them to mark their scent.

- It’s been theorized that the Golden Fleece sought in the Greek myth of Jason and the Argonauts was inspired by the golden takin.

Scientific Name

The scientific name of the takin is Budorcas taxicolor. The genus name Budorcas, of which the takin is the only living member, is actually the combination of two Greek words: bous means cattle (or head of cattle) and dorkas is a type of gazelle. This may be a reference to the animal’s unusual appearance. Taxicolor is probably a reference to the animal’s yellowish hue.

Appearance

The takin’s shaggy coat keeps it warm and snug against the cold and tends to be darker around the face in males

©Yan Simkin/Shutterstock.com

The takin almost looks like several different animals mashed together (hence nicknames like gnu goat and cattle chamois). According to the San Diego Zoo, it has the long, arched snout of a moose, the powerful body and humped shoulders of a bison, and large goat-like hooves with two toes and a spur on each. Both sexes have a set of prominent horns that emerge from the head horizontally and then curve upward toward the sky. The long shaggy coat, which provides insulation from the cold, is a light yellowish color near the front and darker (sometimes reddish brown) near the back. Males also tend to have darker fur around the face. The typical takin animal stands up to 4.5 feet tall at the shoulders and reaches up to 7.3 feet long from head to tail. Males tend to weigh up to 770 pounds, whereas females are slightly smaller and weigh up to 616 pounds. This is about the same size as a motorcycle.

Evolution

Evidence of the takin has been found dating back to the Pliocene, a period which occurred between 2.58 – 5.33 million years ago. The Budorcas teilhardi lived in China while the Budorcas churcheri lived in Ethiopia.

As members of the Caprini, or goat-antelopes, these bovids share the same stocky build and horns common to their extended family.

Their closest relatives include the North American mountain goat to which they bear a striking resemblance and the chamois.

They are also related to the Barbary sheep, the bharal, the ibex, and the tahr. It is worth noting that the very first of them appeared during the Miocene era about 5.333 – 23 million years ago. However, at the time they were somewhat smaller, since they were the size of the serow, another goat-like mammal, which they are also related to.

Types

Tibetan takin share their range with the

giant panda

along with a fondness for bamboo

©Mark_Kostich/Shutterstock.com

There are four main subspecies of takin, including:

- The golden takin (Budorcas taxicolor bedfordi): Found in the mountains of southern China, this ruminant enjoys the protection of a heavy waterproof coat which keeps it cozy and dry in winter.

- The Mishmi takin (Budorcas taxicolor taxicolor): Found in China, India, and Myanmar, this takin is fond of snacking on bamboo shoots. Like the golden takin, it also benefits from a waterproof coat which keeps it safe from the fog.

- The Tibetan takin (Budorcas taxicolor tibetana): Found in Tibet, this bovid shares its range with the giant panda. It roams about bamboo thickets with a surprising agility which belies its stocky frame.

- The Bhutan Takin (Budorcas taxicolor white): Native to Bhutan, this species can be found at elevations of 15,000 feet. Like its other close relatives, it is social; it lives in large herds in summer which break up into smaller groups in winter.

Takin Behavior

Takins have evolved to cope effortlessly with some of the most rugged terrains on the entire planet. While they’re generally incapable of moving quickly, these animals have the ability to leap some 6 feet in the air to cross dangerous gaps. Their amazing balance and deft footwork almost seem to belie their enormous size.

Every year the takin completes a short annual migration in which it gathers together in a large herd consisting of around 300 members for the summer and ascends to around 14,000 feet up the mountain. When the winter arrives, the herd will descend back down into the valleys and break up into smaller groups of around 20 members. These smaller groups are usually composed of adult females, young males, and calves. Older males tend to remain solitary in the winter and do most of the foraging by themselves.

As a member of a larger herd, the takin is a very expressive animal. It has a number of interesting ways to communicate and identify itself. One of the most important methods is vocalizations. If one member of the herd spots danger, then it will make a loud coughing sound to send the other members scurrying for safety. When directly threatened, it will open its mouth, stick out its tongue, and emit a mighty bellow or roar. When it wants something, the takin will make a deep burping sound. When a male is attempting to assert dominance or pick a fight with another male, it will make bellowing sounds while raising its neck and chin. If the calf is separated from its mother, then it makes a panicked mewing type of sound. The mother will then respond with a low guttural call. Other sounds include snorts, whistles, and bugle-like calls. Each of these sounds is accompanied by unique postures and behaviors as well.

Another important method of communication is done entirely via scent. The takin will leave behind pheromones to advertise sexual availability or mark objects. While it doesn’t have specific scent glands like some hoofed mammals, it can secrete a strong-smelling oily substance over its whole body. This substance is said to smell like horse and musk. The takin will also soak its body in urine to convey information about itself as well.

Takin Habitat

The takin is endemic to the rocky alpine forests and meadows, at elevations of around 3,000 to 14,000 feet above sea level, in the eastern Himalayan region near China, Tibet, Nepal, India, Bhutan, and Myanmar. There are four recognized subspecies: the golden takin, the Mishmi takin, the Tibetan takin, and the Bhutan takin. The golden takin, which is native to the Qin Mountains of China’s Shaanxi province, has an unusual gold-colored coat that gets lighter as they age. The Mishmi is native to India and parts of China. The Tibetan and Bhutan takins are from those regions, respectively.

Takin Predators and Threats

Dholes, highly social canids native to Asia may take on an adult talkin

©Nimit Virdi/Shutterstock.com

While the takin has historically been hunted by people for centuries, it is now under serious threat throughout most of its natural range. Besides the constant threat of predation, its numbers have been greatly winnowed by habitat destruction and too much hunting. Farming, mining, road construction, and bamboo cutting are all responsible for disrupting migratory routes and dividing up herds.

What eats the takin?

Only the most fearsome predator such as bears, wolves, leopards, and dholes would dare to take on an adult takin animal. Predators will usually try to isolate individual members of the herd, especially those that are sick, wounded, or young. When threatened, takins may seek safety in dense underbrush. They also have the ability to defend themselves against some predators.

The takin is a herbivore which has an extensive diet consisting of over 130 plat species

©Hung Chung Chih/Shutterstock.com

What does the takin eat?

The takin is an herbivorous browser that spends much of the early morning and afternoon sifting through vegetation. During the summer, the takin consumes grasses, herbs, and the deciduous leaves of shrubs and trees. During the winter, its dietary intake switches to twigs and evergreen leaves. It’s estimated that they eat around 130 different species of plants. Bamboo leaves, oak leaves, and willow and pine bark are just a few of their favorite foods. In order to reach the highest vegetation, the takin will stand on its hind legs with its front feet pressed against the tree. Sometimes its enormous size is even enough to bend the tree downward within reach of its mouth.

As a type of ruminant (like sheep and goats), the takin has a specialized multi-chamber stomach to help it digest the contents of its diet. The softest or smallest food bits are digested in the first chamber of the stomach. The toughest foods (like cellulose) will move into the second chamber, and after being digested for a bit, they will be regurgitated as cud and then chewed over again for a final time. This entire digestive process could take several hours for the toughest foods.

Takin Reproduction and Life Cycle

Takin give birth about 7 or 8 months after mating. Their young are weaned after about a month

©ziegenbock/Shutterstock.com

The takin’s natural reproductive season, which lasts between July and August of each year, is known as a rut. Males will try to compete with each other for access to females by butting heads and shoving the other animal aside. The most dominant males will have several mates per season, while some males may have none at all. Seven or eight months after mating, the mother will try to find some nearby cover and give birth to a single baby (rarely twins), weighing only 11 to 15 pounds.

While it first emerges from the womb in a vulnerable state, the calf gains the ability to walk within three days after birth so it can follow its mother and avoid danger. To camouflage itself from predators, the calf has a dark stripe along the back that slowly fades with age. They are also highly active playmates that engage in head butting and frolicking with each other. The father is thought to play no role in raising the young.

The baby takin animal will be fully weaned from the mother’s milk after about a month or two so it can begin eating solid foods. It takes about 30 months for the young to reach full sexual maturity and begin reproducing. They have a normal lifespan of around 16 to 18 years in the wild and up to 20 years in captivity.

Takin Population

The takin is currently classified by the IUCN Red List as a vulnerable species. Because of the difficulty involved in accessing the harsh terrain of their natural range, population numbers are very difficult to assess, but it’s estimated that probably no more than 12,000 remain in the wild.

View all 136 animals that start with TTakin FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Are takins carnivores, herbivores, or omnivores?

The takin has an herbivorous diet. Since it consumes mostly low-lying vegetation from trees and plants, it is considered to be a browser (as opposed to a grazer).

What kind of animal is a takin?

The takin is actually a member of the order Artiodactyla. The more common term for this order is even-toed ungulate. Even-toed obviously refers to the fact that it bears weight on two toes (for some species it’s four), whereas ungulate is derived from a Latin word for hoof. The takin shares a strong ancestry with cattle, antelopes, goats, and sheep. This is reflected in its complex multi-chambered stomach and the presence of horns.

How many takins are left?

It’s believed that somewhere between 7,000 and 12,000 individuals are left in the wild. Their numbers have declined at an alarming rate from their peak.

Why are takins going extinct?

The main reason for their decline is that parts of their low-lying range (especially in the winter) are vulnerable to habitat loss and exploitation from farming, mining, and other human activities. Hunting for their meat and horns will also cut short their natural lifespan. Conservation laws designed to protect this species are routinely flouted and ignored because they’re difficult to enforce in remote locations.

Where do takins live?

It lives in rugged mountain and valley forests and meadows around the eastern Himalayan region. It is very well-adapted to this sort of alpine lifestyle, which requires it to navigate difficult and dangerous cliffs.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance / Accessed November 13, 2021

- San Diego Zoo / Accessed November 13, 2021

- Animal Diversity Web / Accessed November 13, 2021

- San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Library / Accessed November 13, 2021