Elasmotherium

†Elasmotherium sibiricum

Elasmotherium might have had a monstrous horn, giving it the name "The Siberian Unicorn."

Advertisement

Elasmotherium Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Mammalia

- Order

- Perissodactyla

- Family

- Rhinocerotidae

- Genus

- †Elasmotherium

- Scientific Name

- †Elasmotherium sibiricum

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Elasmotherium Conservation Status

Elasmotherium Facts

- Group Behavior

- Crash

- Fun Fact

- Elasmotherium might have had a monstrous horn, giving it the name "The Siberian Unicorn."

- Biggest Threat

- Climate Change, Humans

- Most Distinctive Feature

- Large Horn

- Distinctive Feature

- Upper Body Fur

- Other Name(s)

- Siberian Unicorn

- Habitat

- Mammoth Steppe

- Predators

- Giant Short Faced Bear, Sabertooth Tiger, Wolves, Lions, Hyenas

- Diet

- Omnivore

View all of the Elasmotherium images!

Description & Size

Elasmotherium sibiricum was a large relative of the rhinoceros. It is an extinct species that certainly crossed paths with humans and may have lived up to 30,000 years ago. Its existence lasted from the Late Miocene Era to only a few thousand years before the end of the Pleistocene, which ended 11,700 years ago.

There’s speculation about the nature of its skin and coat. Based on its environment and similarities to other woolly animals (Woolly Mammoth & Wooly Rhino), Elasmotherium may have had a furry coat.

Some researchers describe this animal as having smooth, hairless skin much as modern rhinoceroses do.

Elasmotherium was an ungulate, which places it in the clade of hooved mammals like giraffes, cows, pigs, deer, and myriad other species. Much like other ungulates, Elasmotherium had 3 functional toes with a vestigial digit that remained unnecessarily through the course of evolution. A key point of interest with Elasmotherium is the purported size of its horn.

The animal is famous for its monstrous, 3-meter horn. That’s roughly 10 feet long, and around three feet longer than the longest horn of a modern rhino. For this reason, many people know this animal as the “Siberian Unicorn” or the “Mudhorn.”

Estimates on the size of the horn come from skeletal remains that show a large dome on the forehead as well as a spinal structure designed to support a large mass near the head. The size of the dome indicates the breadth of the horn’s foundation, whereas the spine suggests how much that horn could have weighed.

Unfortunately, these horns, just like the hairs on your head, were composed of keratin. Keratin doesn’t fossilize in the same way that bones do, so there likely aren’t any Elasmotherium horns perfectly preserved in the soil of the earth.

The size, posture, and gait of Elasmotherium are a point of debate as well. The generally agreed-upon size is over 2 meters tall and 4.5 meters long. This would make Elasmotherium around 6 feet tall, just under the average size of a Woolly Mammoth. Further, it would have weighed roughly 4 tons.

Some paleontologists suggest that Elasmotherium was a semi-aquatic animal, similar in stature to the hippo. Others depict it with a horse-like gait and the ability to gallop. The most likely option is that Elasmotherium shared movement style with the modern white rhinoceros.

These rhinos lift their head slightly and run with pacing similar to that of a horse. In this case, though, the rhino and Elasmotherium’s legs are much shorter and more stout. White rhinos can run almost 30 miles per hour at full speed, though, while Elasmotherium weighed a great deal more and likely topped out at around 15-25 miles per hour.

In any case, we know that there are myriad similarities between modern rhinos and Elasmotherium because of their taxonomical relationship.

Elasmotherium was the last member of the subfamily Elasmotheriinae, which split from modern rhinoceroses 35 million years ago and is one of the closest known subfamilies. While this doesn’t account for all physical appearance and behavior, it gives paleontologists a rough idea of the look and attitude of this Siberian Unicorn.

- Existed through Late Miocene Era, and died out roughly 30,000 years ago

- They May have had a furry upper back, similar to bison

- Ungulate (in the clade of hooved mammals)

- Possible 3-meter horn

- 2 meters tall, 4.5 meters long

- 4 tons in weight

- Running speed of 15-25 miles per hour

©Catmando/Shutterstock.com

Diet – What Did Elasmotherium Eat?

It’s believed that Elasmotherium chewed on rough, even abrasive grasses and plants based on its hypsodont teeth. These are teeth with enamel beneath the gumline to account for gradual wearing down over time.

Further, similar to the modern rhino, Elasmotherium’s head and spine were situated in a way that pointed them downward. This gave them the ability to graze near the soil and eat small plants. In fact, they wouldn’t have been able to reach upward and access plants that grew much higher than the soil.

This suggests that Elasmotherium grazed habitually and likely occupied vast steppes or areas of dense vegetation near bodies of water. It’s likely that Elasmotherium and Woolly Mammoths occupied many of the same spaces.

From 100,000 years ago until the end of the late Pleistocene, then, it’s likely that Elasmotherium lived and grazed on the Mammoth Steppe. This spanned from Western Europe all the way through Eurasia and into North America. This area was dominated by herbivorous ungulates.

Habitat – When and Where It Lived

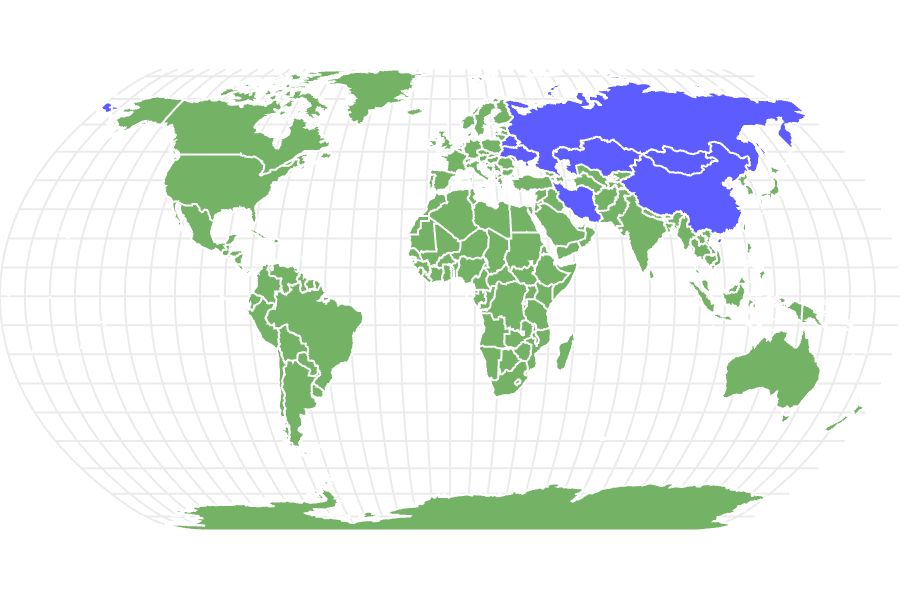

It’s likely that Elasmotherium evolved directly from Sinotherium which means “Chinese Beast.” Fossils from this genus have been found in Kazakhstan, Iran, Mongolia, and China. As a result, the earliest instances of Elasmotherium were found in China. Fossils have also been found in the Pontic-Caspian Steppe, regions of the Middle East, and Central Asia.

Elasmotherium would have occupied these territories from the Late Miocene (20 million years ago) up until at least 39,000 years ago. That’s the age of the most recent fossil, although there could be individuals that lived up through the end of the Late Pleistocene which concluded roughly 11,700 years ago.

Homo sapiens dispersed into Eurasia and occupied the same space as Elasmotherium roughly 60,000 years ago, so people almost definitely interacted with these large relatives of rhinoceroses. There is even Paleolithic cave art that depicts a creature strikingly similar to what Elasmotherium might have looked like.

Threats and Predators

Fortunately for Elasmotherium, the Mammoth Steppe and areas like it were dominated by herbivores. Many of those animals would have looked similar to if not the same, as animals we’re familiar with today.

Animals like oxen, deer, gazelle, horses, and woolly mammoths would have grazed alongside Elasmotherium. That said, massive plains filled with large, peaceful animals are perfect hunting grounds.

Some of the infamous predators of the Pleistocene would have hunted Elasmotherium. The most famous of the group was the Sabertooth Tiger. Simultaneously, they would have contended with lions, wolves, hyenas, bears, and more.

The predator most likely to give Elasmotherium a challenge would have been the Giant Short-faced Bear, also known as the Cave Bear. These monsters stood a whopping 12 feet tall on their hind legs and were larger than any bears in existence today.

Remember that Elasmotherium was a large animal as well. Further, thick skin and a massive horn were great defenses. It’s likely that adult Elasmotherium wouldn’t have been a viable prey source for most of these Pleistocene predators.

Rather, carnivorous predators might have attacked young Elasmotherium. It’s possible that a group of hyenas or a particularly hungry Giant Short-faced Bear would have hunted Elasmotherium from time to time, but it wouldn’t have been the norm.

Fossils and Discoveries

The first fossil of Elasomtherium sibiricum was interpreted in the early 1800s. Gotthelf Fischer von Waldheim, a German paleontologist, was given access to the bone by Moscow University.

Interestingly, this bone was only the lower left jaw of the creature and it had been in the possession of Ekaterina Dashkova, a Russian princess and central figure in the Russian enlightenment. It wasn’t until 1877, however, that the species was added to the Elasmotheriinae family.

There are hundreds of Elasmotherium discoveries throughout Asia and Eastern Europe. These discoveries consist mostly of teeth and skull fragments, although some nearly-complete skeletons have been discovered.

Extinction – When Did It Die Out?

It’s believed that Elasmotherium died out anywhere from 20,000 to 40,000 years ago. Their extinction is attributed to the Quaternary extinction event or “Pleistocene Extinction.”

This extinction period, which ranges from about 130,000 years ago to roughly 8,000 years ago, is marked by drastic changes in climate and the resulting extinction of thousands of species. The first migrations of human beings across the globe occurred during this time as well.

A cooling shift in the climate restructured the flora of the environment, causing most of the substantial plant life to recede and leaving room for only small plants like mosses and lichen. Large herbivores over roughly 100 pounds were unable to find enough food.

As humans expanded and hunted the land, they also disrupted ecosystems. The most recent Elasmotherium fossil remains coincide with this time period, so it’s believed that the factors above caused Elasmotherium’s extinction.

Similar Animals to Elasmotherium

Similar animals to Elasmotherium sibiricum include:

- White Rhinocerous – While Elasmotherium is close in relation to most rhinoceroses, the white rhinoceros is believed to have the most similar gait and posture.

- Woolly Mammoth – It was long believed that Elasmotherium and the Woolly Mammoth were related. While this isn’t true, the two animals would have occupied the same spaces and positions in ecosystems.

- Tapir – While it doesn’t look like it, Tapir and Rhinos share a common lineage. They are both odd-toed ungulates and exist within the order Perissodactyla.

Want to Learn More About Ancient Animals?

- When Did Neanderthals Go Extinct?

- Cretaceous Period: Major Events, Animals, and When It Lasted

- The 9 Coolest Extinct Animals to Ever Walk the Earth

- Discover the 30 Foot, Armored Sea Monster With a T-rex Bite

Elasmotherium FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

When was Elasmotherium alive?

Elasmotherium existed from the late Miocene (ending 5.3 million years ago) nearly through the end of the Late Pleistocene (ending 11,700 years ago). Researchers believe that Elasmotherium split from its previous subfamily around 35 million years ago. The most recent estimate is that the animal lived up until at least 39,000 years ago, although there’s also a less-reliable estimate of 26,000 years ago.

How big was Elasmotherium?

Elasmotherium is believed to have been roughly 2 meters (6.5 feet) tall and 4.5 (15 feet) long. That’s around the size of a Woolly Mammoth or a small modern elephant. It also weighed around 4 tons.

How big was Elasmotherium's horn?

There’s debate on the size and existence of the horn. The image of a large “Siberian Unicorn” comes readily to the imagination, but the “horn” may have been more of a resolution crest. Elasmotherium skulls have domes with 3 feet of circumference and 5 inches of depth. These, along with back support, imply a large horn that could have weighed a lot.

It’s also possible that the dome could have supported something smaller and rounder than a traditional horn. If popular depictions are true, however, the horn would’ve been 6 or 7 feet long.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- Nature.com, Evolution and extinction of the giant rhinoceros Elasmotherium sibiricum sheds light on late Quaternary megafaunal extinctions (2018) nature.com/articles/s41559-018-0722-0 / Accessed July 1, 2022

- Dinopedia, Elasmotherium / Published October 28, 2022 / Accessed July 1, 2022

- ThoughtCo., Elasmotherium / Published February 4, 2022 / Accessed July 1, 2022

- Prehistoric-wildlife.com, Elasmotherium / Published January 3, 2019 / Accessed July 1, 2022

- Bear.org, The Giant Short-Faced Bear / Accessed July 1, 2022

- Bering Land Bridge, Giant Short Faced Bear (2015) nps.gov / Accessed July 1, 2022