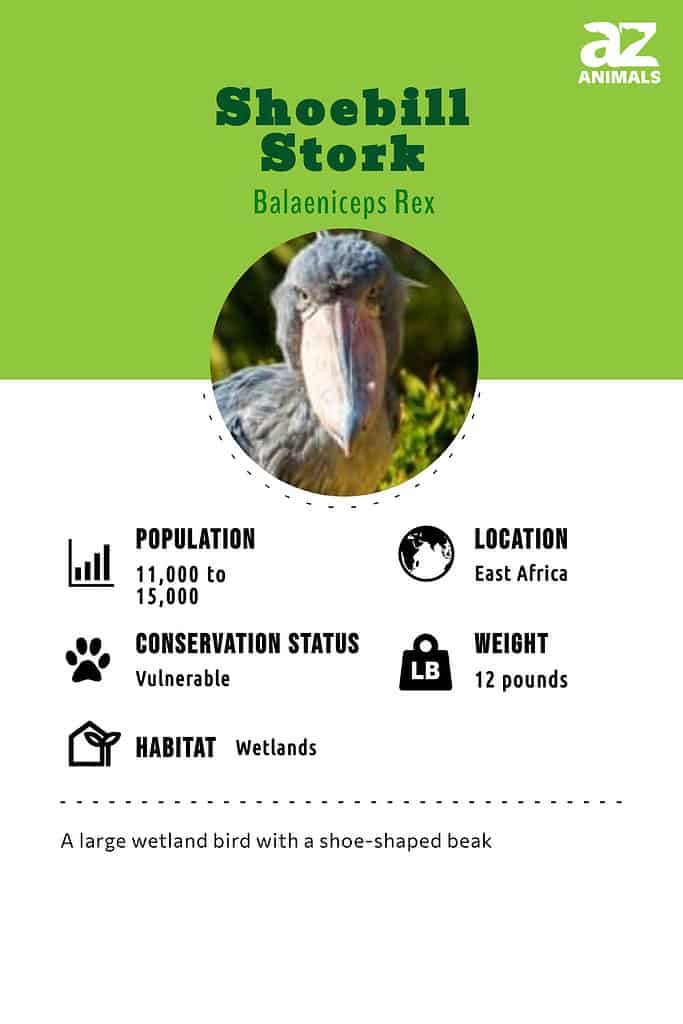

Shoebill Stork

Balaeniceps rex

Adults greet each other by clattering their bills together.

Advertisement

Shoebill Stork Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Aves

- Order

- Pelecaniformes

- Family

- Balaenicipitidae

- Genus

- Balaeniceps

- Scientific Name

- Balaeniceps rex

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Shoebill Stork Conservation Status

Shoebill Stork Facts

- Prey

- Fish, snakes, frogs, turtles, lizards, and more

- Fun Fact

- Adults greet each other by clattering their bills together.

- Estimated Population Size

- 11,000 - 15,000

- Biggest Threat

- Habitat destruction

- Most Distinctive Feature

- Shoe-shaped bill

- Other Name(s)

- Whaleheaded stork

- Wingspan

- 8ft

- Incubation Period

- 30 days

- Habitat

- Wetlands

- Predators

- Humans and crocodiles

- Diet

- Carnivore

- Type

- Bird

- Common Name

- Shoebill stork

- Number Of Species

- 1

- Location

- East Africa

- Nesting Location

- Small islands or floating vegetation

- Age of Molting

- 3-4 months

View all of the Shoebill Stork images!

Standing tall on its long, stilt-like legs, the shoebill stork cuts an imposing figure as it stalks slowly through the dense wetlands for its prey without making a sound.

Although it was once classified as a stork, it’s actually more closely related to the herons, hamerkop, and pelicans within the completely separate order of Pelecaniformes. The shoebill is the only living member of its family.

4 Amazing Shoebill Stork Facts

- Like many birds, the shoebill uses a technique called gular fluttering to stay cool. This is the act of opening its mouth and fluttering its throat muscles to release excess heat. The shoebill will also urinate on its own leg, which will then have a cooling effect after evaporating.

- While in flight, the shoebill retracts its neck against its body.

- Shoebills will fiercely guard a territory stretching more than a square mile.

- The bird’s territorial range coincides very strongly with the occurrence of the papyrus plant.

Do you want to learn more about Shoebill Stork? Read “10 Incredible Shoebill Stork Facts”.

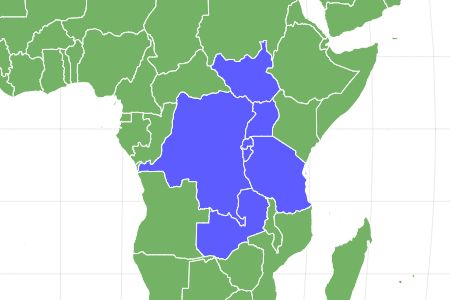

Where to Find Them

The Shoebill stork lives in Uganda’s wetlands.

©Petr Simon/Shutterstock.com

The shoebill stork is commonly found in the dense marshlands and freshwater swamps of East Africa, including the countries of Uganda, Tanzania, South Sudan, and Zambia.

Shoebill Stork Nests

The stork’s nest is usually located on an island or a mass of floating vegetation in the middle of the swamp. It is made from a collection of reeds, papyrus, and grasses.

Scientific Name

The majestic Shoebill Stork of the wetlands is an excellent fisherman.

©Petr Simon/Shutterstock.com

The scientific name of the shoebill stork is Balaeniceps rex. The genus name Balaeniceps is actually the combination of two Latin words that roughly translate into English as “whale-headed.” Rex, meanwhile, means king or ruler in Latin, which refers to the bird’s exceptionally large size.

Evolution and Origins

Shoebill storks have been on Earth for at least 30 million years.

©Marek Mihulka/Shutterstock.com

The shoebill stork (Balaeniceps rex) is a unique bird species with a fascinating evolutionary history. While the exact origins of this enigmatic bird remain unclear, scientists believe that it belongs to the Pelecaniformes order, which includes pelicans and other large waterbirds.

Fossil evidence suggests that shoebill storks have been around for at least 30 million years, with their earliest ancestors likely living in Africa during the Eocene epoch. Over time, these birds evolved to adapt to new environments and ecological niches by developing specialized physical features such as their distinctive bill shape and size.

One theory about how shoebills evolved their iconic footwear is that they developed them over time as an adaptation for catching prey in shallow waters or muddy swamps. Their bills are uniquely shaped like clogs or shoes – hence the name “shoebill” – allowing them to probe into murky waters without getting stuck in mud or debris.

Despite being ancient creatures, shoebills are still thriving today thanks to successful conservation efforts aimed at protecting their natural habitats from human encroachment. As we continue to learn more about these remarkable birds through scientific research and observation, we can gain valuable insights into our planet’s complex web of life and better understand how different species evolve over time.

Shoebill Stork

The Shoebill stork, Balaeniceps rex, also known as Whalehead or Shoe-billed Stork, is a very large Stork-like bird.

©Petr Simon/Shutterstock.com

The appearance of the shoebill stork has sometimes been likened to a dinosaur. It’s characterized by long, spindly legs, blue to grey plumage, a powdery down on the breast and stomach, and a small tuft of feathers at the back of the head that forms a crest. By far, the most prominent characteristic, though, is the massive shoe-like bill that ends in a curved hook, rightly earning this bird the nickname of whale headed. As one of the largest bills among all living birds, it’s used to catch and swallow large prey whole. Much of the bill is composed of hard keratin, the same substance as nails and horns. As you can probably imagine, this large bill also needs a strong head, neck, and body to support it. Standing between 4.5 and 5.5 feet in height (and with a weight of 12 pounds), the shoebill stork is among the largest birds in the world. Males are slightly larger in terms of body and bill size.

Behavior

The shoebill stork can perhaps be described as an anti-social bird. Any encounters with other shoebills during daytime foraging excursions are generally unwanted and undesirable. Even its mating partner will usually forage on opposite sides of the territory. That does not mean it is bereft of all social niceties, however. The shoebill will actually employ a technique called bill clattering to greet each other by pressing their bills together. Though otherwise silent, they will also make a whining or mewing sound to communicate.

Despite its enormous size, the shoebill stork has the ability to soar high above the wetlands on gusts of thermal wind. But in order to be born aloft, the bird must first make a large leap, and a few heavy wing beats to catch a ride on the thermals.

Diet

A Shoebill stork loves to eat fish, like this lungfish.

©iStock.com/Michel VIARD

The shoebill has two basic hunting strategies: “stand and wait” or “wade and walk slowly,” both of which occur right near the edge of the water. When it lunges, the bird’s entire head actually collapses into the water. The stork will probably not get a second chance because it can take a few minutes to regain its balance and try standing again. After capturing prey, this bird will swing its head back and forth to expel vegetation from its mouth and then decapitate its victim or swallow it whole. The shoebill stork prefers to nest near low-oxygen water, where fish need to surface frequently to breathe.

What does the shoebill stork eat?

The shoebill likes to eat catfish, tilapia, bichirs, lungfish, and even water snakes. If no other food is available, then it may turn to lizards, turtles, frogs, mollusks, and even young crocodiles.

Predators and Threats

Anything that threatens the delicate balance of the wetland ecosystem also threatens the shoebill stork.

©FARUK BUDAK/Shutterstock.com

The Shoebill Stork, also known as the Whalehead or Balaeniceps rex, is a unique bird species found in the wetlands of Africa. Although it is an apex predator in its habitat, the Shoebill stork does face predators and threats that can impact its population.

One of the major predators of adult shoebills is Nile crocodiles (Crocodylus niloticus), which can easily overpower them using their powerful jaws and strong tails. Other potential predators could include large mammals such as hyenas or leopards, but these encounters are rare.

In addition to natural predators, human activities pose significant threats to shoebills. Habitat destruction due to deforestation and land development has led to a rapid decline in available wetland habitats for this species. Furthermore, hunting by humans seeking meat or feathers for trade further threatens both populations and individual birds.

Conservation efforts have been put in place across parts of Africa where shoebill populations exist to protect them from these threats. These efforts include establishing protected areas for breeding grounds, regulating hunting practices through legislation enforcement, and raising awareness about the importance of conservation measures among local communities who live near these habitats.

What eats the shoebill stork?

On account of its body size and big, sharp beak, the shoebill stork has few predators besides crocodiles and humans.

Reproduction, Babies, and Lifespan

A pair of Shoebill Storks both take part in incubating eggs and raising their young

©Ward Poppe/Shutterstock.com

The shoebill stork invests enormous resources into the care of its young. By forming long-term monogamous pairs, they can divide up many aspects of parental duty, including nest construction, incubation, feeding, and child-rearing. The stork times its mating activities to coincide with the start of the dry season so the chicks are ready to fledge when the rains begin. The parents are very fastidious about caring for the unhatched young. They will pour water over the eggs to keep them cool, cover them in wet grass, and turn them over with their feet or bill.

After about a month, the chicks will hatch with a darker shade of silvery grey down and a much smaller bill than their adult counterparts. Making a hiccup sound to communicate, they will need to be fed regurgitated food several times a day. However, if food is particularly scarce, then only one baby may survive beyond the juvenile stage. As depicted in a well-known BBC documentary, the shoebill parents will sometimes deliberately leave a chick to die. While this may seem cruel, it is a legitimate child-rearing strategy that ensures the strongest baby will survive.

Chicks will become capable of flight after about three to four months of age. At that point, the parents’ duty will be done, and the chicks will leave the nest. If they survive the juvenile stage, then the shoebill can live up to 35 years in the wild.

Population

The Shoebill stork populations are very low. There are only 10-15K of them left in the world.

©Petr Simon/Shutterstock.com

Despite the difficulty of accessing shoebill habitats, it’s been estimated that some 11,000 to 15,000 of these birds remain. The IUCN Red List currently classifies it as vulnerable to extinction. Most African countries within its range already extend protection to the shoebill, but habitat loss has continued apace for decades.

View all 306 animals that start with SShoebill Stork FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Does the shoebill stork migrate?

The shoebill does not migrate, but in certain locations, it might make seasonal voyages between nesting and feeding sites.

How many eggs does the shoebill stork lay?

The shoebill will lay up to three eggs in the breeding season.

How fast does shoebill stork fly?

This bird can fly at speeds up to 30 miles per hour.

What is the shoebill stork’s wingspan?

The shoebill has a typical wingspan of nearly 8 feet.

When do shoebill storks leave the nest?

A baby shoebill will leave its nests after about four months.

Are shoebill storks dangerous?

The shoebill actually behaves very calmly and docile around humans. It often allows people to approach relatively close. Some have said its stare can be intimidating, but this is probably just a result of its fierce-looking and implacable eyes.

How many shoebill storks are left?

No more than 15,000 shoebills are left in the wild.

Can a shoebill kill you?

While the beak is quite sharp, the shoebill has never been known to kill a person.

Where do shoebill storks live?

The shoebill lives in the swamps and wetlands of East Africa.

Are shoebill storks prehistoric?

Many people seem to think that the shoebill appears like a prehistoric dinosaur, but besides the fact that all birds descended from dinosaurs, there’s nothing particularly prehistoric about it. The shoebill is just as “modern” as any closely related bird.

What is the height of shoebill storks?

The shoebill usually grows no larger than 4.5 feet in height and 12 pounds in weight.

Who would win in a fight: Shoebill Storks vs, Crocodiles?

A crocodile would win a fight against a shoebill stork.

The size, power, and brutal ambush techniques of crocodiles give them a massive advantage against these birds.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- Animal Diversity Web / Accessed April 25, 2021

- San Diego Zoo / Accessed April 25, 2021