Mule Deer

Odocoileus hemionus

Mule deer can run up to 45 miles per hour.

Advertisement

Mule Deer Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Mammalia

- Order

- Artiodactyla

- Family

- Cervidae

- Genus

- Odocoileus

- Scientific Name

- Odocoileus hemionus

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Mule Deer Conservation Status

Mule Deer Facts

- Prey

- Vegetation

- Main Prey

- Grass, leaves, berries

- Name Of Young

- Fawn

- Group Behavior

- Solitary

- Herd

- Fun Fact

- Mule deer can run up to 45 miles per hour.

- Estimated Population Size

- 4 million

- Biggest Threat

- Habitat encroachment and degradation.

- Most Distinctive Feature

- Large ears.

- Distinctive Feature

- Males have horns.

- Other Name(s)

- California mule deer

- Gestation Period

- 190-200 days

- Temperament

- Mild-mannered, sedentary, not agressive

- Age Of Independence

- 2 years

- Litter Size

- 1-4

- Habitat

- Mountainous forests, scrublands

- Predators

- Cougar, wolf, bobcat, lynx, grizzly bear

- Diet

- Herbivore

- Average Litter Size

- 2

- Lifestyle

- Nocturnal

- Favorite Food

- Grasses, leaves, berries

- Common Name

- Mule deer

- Special Features

- Large mule-like ears

- Origin

- Descended from black-tailed deer

- Number Of Species

- 4

- Location

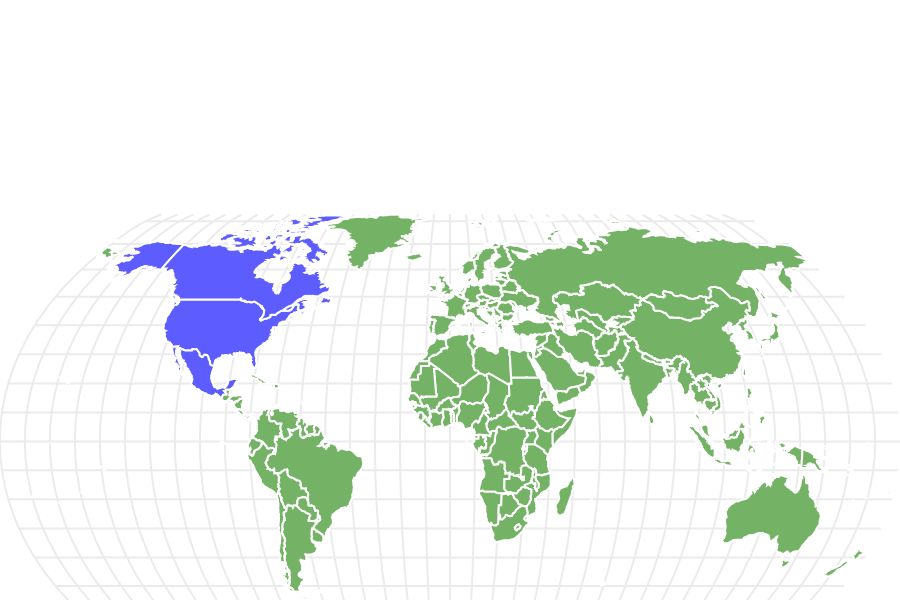

- Western North America

- Migratory

- 1

Mule Deer Physical Characteristics

- Color

- Brown

- Grey

- Skin Type

- Fur

- Top Speed

- 45 mph

- Lifespan

- 10 years

- Weight

- 200-400 pounds

- Height

- 31-42 inches.

- Length

- 3.9-6.9 feet

- Age of Sexual Maturity

- 1-2 years

- Age of Weaning

- 5-6 months

- Venomous

- No

- Aggression

- Low

View all of the Mule Deer images!

“Mule deer are one of the few deer species that can give birth to triplets or quadruplets!”

Mule Deer Summary

The mule deer is a species closely related to white-tailed and black-tailed deer. It is a successful species that is not endangered and enjoys a range in the mountains of western North America from Alaska to Mexico. Mule deer can have up to four babies at a time, a rarity for most deer species. Several species of carnivores prey on mule deer, but the biggest threat to them comes from humans through the loss and fragmentation of their habitat, disruption of their migratory patterns, and even the practice of feeding them in the winter which spreads disease and creates overpopulation.

Mule Deer Facts

- Mule deer eat over 800 varieties of vegetation.

- Like cattle and sheep, mule deer are ruminants that “chew the cud,” which means they regurgitate and chew previously-swallowed vegetation.

- They usually have two babies but can have up to four on occasion.

- Mule deer are named for their large ears, which look like those of a mule.

- They run by “stotting” or “pronking” like gazelles: jumping up and landing stiff-legged on all four hooves at once.

Mule Deer Scientific Name

The scientific name of the mule deer is Odocoileus hemionus. It belongs to the Cervidae family of the Mammalia class. They and white-tailed deer are believed to have evolved from black-tailed deer. All three species can interbreed. There are 8 subspecies of the mule deer.

Mule Deer Appearance

Mule deer bucks grow a new set of antlers each year! This male displays a rare genetic trait known as a drop tine, that is to say, a tine on its

antler

that is pointing downward.

©iStock.com/Jeff Edwards

The mule deer is a species most recognizable by its large ears, that resemble those of a mule. They have been called “The Deer of the West” and are considered an iconic example of North American wildlife.

Compared to other deer species, they are medium-sized, measuring on average 31-42 inches at the shoulder. From nose to tail they are 3.9-6.9 feet long They weigh 200-400 pounds but bucks, or adult males, have been known to get as heavy as 460 pounds. Does, or adult females, are smaller and lighter, weighing 95-198 pounds.

Their coloration is reddish-brown to grey-brown. They look similar to white-tailed deer, found in the eastern United States and Canada, but unlike them, they have a black-tipped tail and antlers that fork as they grow rather than branching from a main beam as the white-tail deer does.

Bucks grow new antlers every year starting in March or April and ending in August or September. After mating season, males shed their antlers usually between January and March.

Mule Deer Behavior

Some mule deer live solitary lives while others stay in small groups of 3-7. Males may join females in common herds in the winter, but they separate in spring. They are sedentary and largely silent except during mating season or in danger when they can issue a rallying call similar to a dog’s bark. They can run, but often prefer moving by “stotting” or “pronking”—a gazelle-like behavior of jumping off the ground and landing with stiff legs on all four feet.

In the hot western summers, mule deer ascend as high as 6,500 feet up the mountains to reach cool meadows, but in autumn when bad weather starts they return to lower slopes and valleys where food sources have not yet been covered in snow. Some migrate long distances between their summer and winter ranges. The longest mule deer migration scientists have discovered was in Wyoming and was 150 miles long. They remember their migration routes and continue to follow them even when the availability of food has changed because of weather conditions or the degradation of their habitat.

Mule Deer Habitat

The mule deer is native to western North America: Canada, the United States, and Mexico. It ranges all the way from the Arctic Circle to the Baja Penninsula of Mexico. They have also been introduced into Argentina and Kauai, Hawaii but have not reached large numbers there.

Mule deer prefer woods and scrublands that provide adequate food and shelter. They can thrive in a wide range of climate zones as seen by the huge geographic extent of their habitat.

Mule Deer Diet

Mule deer eat nearly 800 species of plants. They browse on shrubs, weeds, leaves, twigs and grasses and eat beans, pods, nuts and acorns, berries and mushrooms when they can find them. Near populated areas they may wander into farmland and yards to eat crops and landscaping plantings. They are ruminants, which means they swallow vegetation and allow it to ferment, then regurgitate and chew it again.

They store fat in the fall, particularly in October, which helps them survive until spring when more food becomes available. In severe winters some people put out food for mule deer to prevent them from starving. Wildlife agencies caution against doing so. It disrupts the natural migratory patterns. It also spreads disease when the deer gather for food and can lead to overpopulation.

Mule Deer Predators, Threats, and Conservation Status

The main natural enemies of the mule deer are coyotes, wolves, and cougars. Bobcats, lynx, wolverines, American black bears, and grizzly bears also may attack them. Predators prefer to attack fawns and sick or wounded deer. The main defense they have against natural predators is by running away. They can reach speeds of up to 45 miles per hour, making them one of the fastest animals in North America.

As with many animals, human activity is their greatest long-term threat. Although the mountainous areas they frequent are thinly populated by humans, this is changing in some areas. For example, the population of Colorado has grown by over 2.2 million people since 1980! Human activities that disrupt the natural habitat include logging, mining, agriculture, livestock grazing, fencing, highways, and suburban sprawl. These can reduce the size of the habitat, frighten away the wildlife, and disrupt migratory patterns. In some areas, highway departments have constructed overpasses or underpasses covered in vegetation to allow animals to move safely across highways. Here’s a video showing what that looks like.

Harm can also come from well-meaning people who put out feed for them in the winter to prevent them from starving. As a result of this easily available food source, migrating deer may continue to stay in an area with harsh winters rather than moving on to warmer areas of their range. Deer congregating to feed come in close contact with one another and can spread disease. To the extent that feeding helps with winter survival, it can create overpopulation, leading to over-grazing, disease, and larger numbers of deer wandering into roads and neighborhoods.

Mule Deer Reproduction, Babies and Lifespan

Mating season for mule deer begins in the fall. Males compete with one another for does. Does may mate with more than one buck during the season. Gestation takes 190-200 days. Usually, the mother gives birth to twins but first-time mothers may only give birth to one fawn. On rare occasions, does may give birth to three or even four offspring. They are born in the spring. The typical survival rate for fawns is 50%. They stay with their mothers through the summer and are weaned in the fall, after 60-75 days of nursing. The typical deer lifespan is 10 years.

Mule deer are typically born in the springtime.

©iStock.com/:Akchamczuk

Mule deer do hybridize with black-tailed and white-tailed deer. Their offspring with white-tailed deer are less adapted to the western environment, having more difficulty running and fending off predators.

Mule Deer Population

The wild mule deer population is estimated at approximately 4 million. They are not endangered, and are considered an animal of “least concern” by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

Up Next

- Black-tailed deer

- White-tailed deer

- Roe deer

- Deer Season In Nebraska: Everything You Need To Know To Be Prepared

Mule Deer FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

How did the mule deer get its name?

The mule deer has long ears like those of a mule. That’s how it got its name.

Are mule deer endangered?

No. They are considered a species of “least concern.” There are over 4 million in the wilds of western North America, from the Arctic circle to northern Mexico.

Should you feed mule deer in the winter?

No. Wildlife experts caution that this disrupts the deer’s migratory patterns, causes them to spread disease as they congregate for food, and leads to overpopulation.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- Wikipedia / Published September 16, 2022 / Accessed September 16, 2022

- Britannica / Published February 18, 2020 / Accessed September 16, 2022

- Mule Deer Foundation / Published January 1, 2021 / Accessed September 16, 2022

- New York Times / Published May 31, 2021 / Accessed September 17, 2022

- North American Nature / Published January 1, 2022 / Accessed September 17, 2022