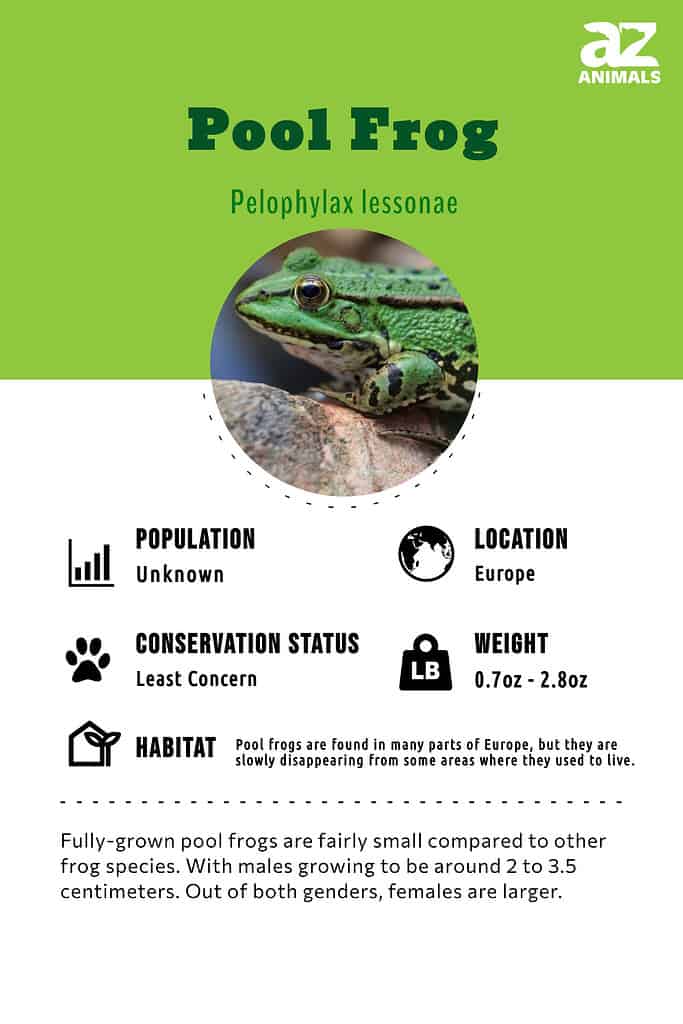

Pool Frog

Pelophylax lessonae

The rarest amphibian in the UK!

Advertisement

Pool Frog Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Amphibia

- Order

- Anura

- Family

- Ranidae

- Genus

- Pelophylax

- Scientific Name

- Pelophylax lessonae

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Pool Frog Conservation Status

Pool Frog Facts

- Lifestyle

- Solitary

- Favorite Food

- Insects

- Type

- Amphibian

- Average Clutch Size

- 1500

- Slogan

- The rarest amphibian in the UK!

View all of the Pool Frog images!

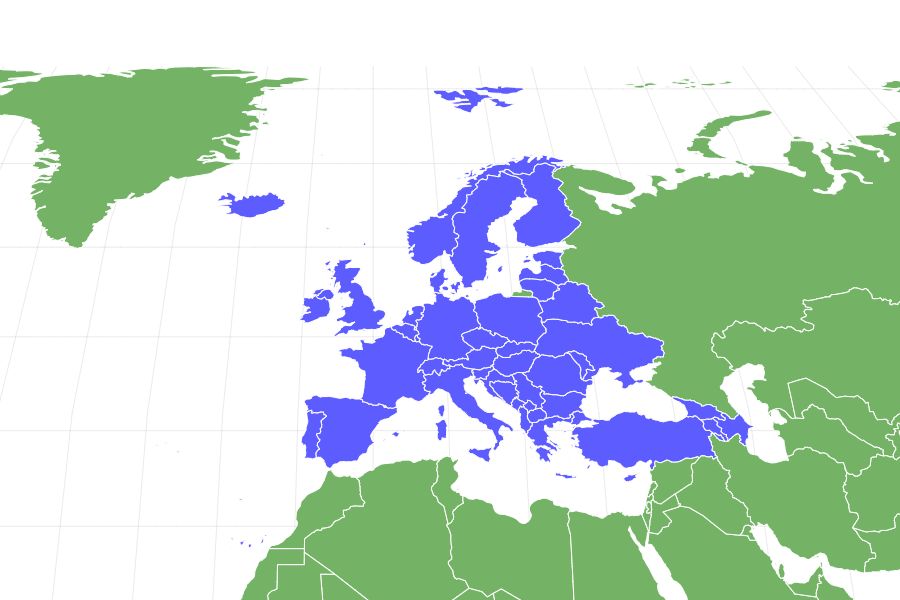

The pool frog has a wide range across much of Europe, but it appears to be in steady retreat across some parts of its former territory.

The heaviest toll appears to have fallen on the native pool frog populations of Britain. The UK frogs went completely extinct in the mid-1990s and had to be reintroduced from Sweden. The culprit for this demise appears to be pollution and habitat loss to which these frogs are particularly vulnerable.

As the name suggests, this species has an affinity for small pools of water, and when the weather turns frosty, it hibernates for the winter.

3 Incredible Pool Frog Facts!

The pool frog is scientifically known as

Pelophylax lessonae.©D. and S. Langenberg/Shutterstock.com

- One of the more interesting facts is that the pool frog has the ability to interbreed with the closely related marsh frog to produce a hybridized animal called the European edible frog. These male and female edible frogs can in turn produce viable offspring with the pool and marsh frogs, but if they try to mate with each other, then only infertile offspring will tend to result. The edible frog has green and yellow colorations with black stripes and splotches over its body.

- Like most other amphibians, the pool frog has highly porous skin that can absorb oxygen and exchange gasses. In other words, it can quite literally breathe through its skin. This means it needs to be constantly moist to exchange gasses. However, the porous skin is also very susceptible to pollution.

- The pool frog’s camouflage colors allow it to blend in with the environment and evade hungry predators.

Scientific Name

Pool frogs are native to parts of Europe, including the United Kingdom, and they prefer freshwater habitats like ponds, ditches, and marshes.

The scientific name of the pool frog is Pelophylax lessonae. This species was named in honor of the 19th-century Italian zoologist Michele Lessona, who specialized in amphibians. The pool frog was formerly a member of the genus Rana (the pond frogs), which also includes the European common frog, but it was later moved to the genus Pelophylax, or the water frogs of Europe and Asia. The name Pelophylax appears to be the combination of two Greek words meaning mud (pelos) and sentinal (phulax).

There is a closely related species called the Italian pool frog, which occupies Italy, Sicily, Corsica, Sardinia, and Elba. Both of these species are a member of the same genus, Pelophylax, but they’re distinct enough from each other to warrant different species classifications.

Evolution and Origins

Pool frogs have greenish-brown skin with darker spots. This helps them blend into their watery environments.

The oldest known fossil of a “proto-frog,” Triadobatrachus, originates from the Early Triassic period in Madagascar. However, based on molecular clock dating, their origins from other amphibians may date back even further to the Permian period, which was approximately 265 million years ago.

In fact, the first larger groups of amphibians began to appear about 370 million years ago during the Devonian period. They came from fish with leg-like fins, sort of like today’s coelacanth and lungfish.

These ancient fish had fins with joints and digits that helped them crawl on the sea floor. These fish then evolved into different types of fish and frogs that we know today.

Appearance

Adult pool frogs are relatively small, with males growing to around 2 to 3.5 centimeters. Females are larger.

©PaulSat/Shutterstock.com

Like many other species of frog, the pool frog has a pointed head, long legs, webbed hind feet, and horizontal pupils, but the easiest way to identify them is their color. They have a brown or green body color with big dark blotches, a white stomach, and a light yellow or green stripe running straight along the back. The exact arrangement of colors and patterns varies between populations and even individuals.

The pool frog is a very small creature that measures not much more than 2.3 to 3 inches in size. Males are slightly smaller than females and have two big inflatable vocal sacs on the side of their heads. These sacs serve as a means to amplify the male’s mating call when it is time to breed.

Pool Frog vs. Common Frog

During the breeding season, male pool frogs emit a distinctive, resonant “purring” call to attract females.

©Aleksey Krivets/Shutterstock.com

The pool frog and common frogs are sometimes mistaken for each other due to their similar size and appearance and their overlapping range in Europe. The main differences are that the common frog has a more rounded head, shorter legs, and a more pronounced brown or even yellow coloration around the body.

Lacking the large pouches on the sides of the head, the common frog produces more of a purring sound in the breeding months of February to March. The pool frog has a later breeding season in May or June.

Behavior

Breeding typically occurs in the spring, and female pool frogs lay their eggs in shallow water.

The pool frog is a solitary animal that lives and hunts on its own. The only time it intermixes with members of its own species is in the May to June breeding season when the male frog makes a quacking-like sound at night to attract a suitable female. By passing air between the lungs and the air sac, the frog creates a vibrating sound in the throat that can carry long distances. The downside of this approach is that it can alert predators to the frog’s location. That is why it only croaks when absolutely necessary.

As a cold-blooded amphibian, the pool frog is unable to maintain a consistent internal body temperature. Instead, the body temperature fluctuates in response to the surrounding conditions. Its behavior is oriented around the daily seasonal fluctuations in the temperature of its environment. For instance, in order to escape the extreme cold, the pool frog hibernates between the months of October and April under logs or inside tree hollows.

Habitat

The pool frog has an extensive range across much of Europe as far east as Russia. However, they appear to be declining in parts of northern Europe, including Norway and Sweden. They were once widespread across the United Kingdom as well before disappearing completely from the island in the 1990s. Based on fossil studies and genetic analysis, it is believed that these UK populations were entirely unique to Britain and dated back to Saxon times in the early Middle Ages. These UK populations were closely related to the Scandinavian pool frogs.

The pool frog lives in permanent puddles, ponds, or marshlands with plenty of dense vegetation. It sometimes likes to take up residence in places where there are streams or rivers nearby. The frog spends a great deal of its life in or around these bodies of water, especially in the summer.

Diet

Wherever it’s found, these frogs play an important role in the ecosystem by limiting the number of small pests in the environment. Their leaping ability and long tongue are the main means of capturing prey.

What does the pool frog eat?

As a young tadpole, the frog’s diet consists of algae and decaying organic material. After undergoing its metamorphosis, the juveniles graduate to flies and their larvae. An adult pool frog feeds primarily on insects, worms, and other small invertebrates.

Predators and Threats

These frogs face several threats from pollution, drainage, diseases, and habitat loss from agriculture or residential development. These factors have caused numbers to decline throughout parts of its natural range.

What eats the pool frog?

An adult frog is preyed upon by foxes, snakes, herons, otters, and other carnivorous animals. The tadpoles are preyed upon by some insects and fish.

Reproduction, Babies, and Lifespan

The frog’s breeding season begins with the onset of the warmer months in May or June. As mentioned previously, the male makes a raucous quacking sound with its big cheek pouches to attract an appropriate mate. After mating, the female will lay a cluster of 400 to 4,000 brown and yellow eggs near the surface of the water. The exact number depends upon several factors such as the temperature of the surrounding environment.

The tadpole is the first stage of the frog’s development. With its external gills and long tail, the tadpole is adapted to survive the aquatic pond or pool from which it originally spawned. Since the parents invest almost no time and effort into raising the young, the tadpoles must begin feeding immediately to survive. Many of them are eaten early by predators and don’t survive this initial stage.

Around August or September, the tadpoles undergo their remarkable transformation into full adulthood. Their gills are covered up, they lose their tails, and they become full adult frogs. However, it takes about two or three years before the frogs can begin to reproduce on their own. They have a life expectancy of about six to 12 years in the wild.

Population

According to the IUCN Red List, these frogs are considered to be a species of least concern. It is very difficult to estimate the number of pool frogs remaining in the wild. However, the facts suggest that local populations have been in decline throughout parts of Europe due to pollution and habitat loss. The United Kingdom once had its own distinctive population of pool frogs, but after a huge decline in numbers throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the pool frog finally disappeared from Britain in 1994 or 1995.

In order to revive this species in the UK, conservationists collected some Swedish pool frogs between 2005 and 2008 and introduced them to two Norfolk sites. The Forest Commission made special efforts to restore special ponds in which the frogs could thrive. Once these populations were firmly established, conservationists then introduced them to other sites in the UK so they could repopulate the country. These frogs are very well-protected under UK law, which makes it an offense to kill, injure, sell, or trade this species.

Zoos

These frogs are not exhibited at any American zoo.

View all 192 animals that start with PPool Frog FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Are Pool Frogs herbivores, carnivores, or omnivores?

Pool Frogs are Carnivores, meaning they eat other animals.

Where do pool frogs live?

The pool frog lives in permanent puddles, ponds, or marshlands across most of Europe. Its range extends between France in the west and Russia in the east and between Sweden in the north and Romania and Serbia in the south.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- Discover Wildlife, Available here: https://www.discoverwildlife.com/animal-facts/amphibians/facts-about-pool-frogs/

- Amphibian and Reptile Conservation, Available here: https://www.arc-trust.org/pool-frog

- Britannica, Available here: https://www.britannica.com/animal/marsh-frog#ref166320

- BBC News, Available here: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/england/norfolk/4143224.stm