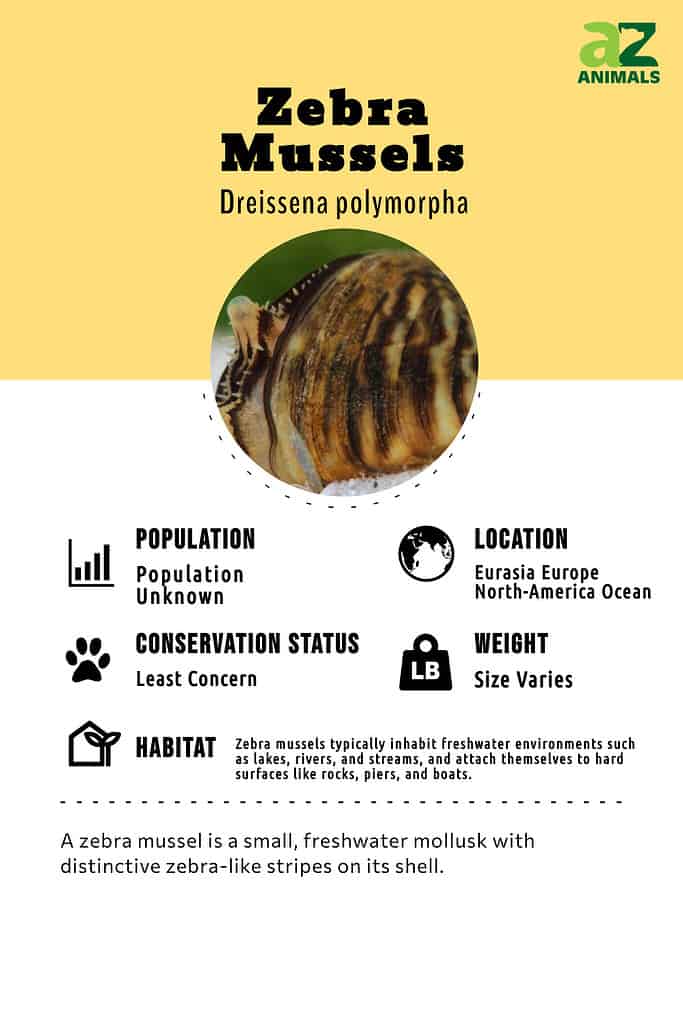

Zebra Mussels

Dreissena polymorpha

A female zebra mussel can deposit 30,000 to 1,000,000 eggs each year!

Advertisement

Zebra Mussels Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Mollusca

- Class

- Bivalvia

- Order

- Myida

- Family

- Dreissenidae

- Genus

- Dreissena

- Scientific Name

- Dreissena polymorpha

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Zebra Mussels Conservation Status

Zebra Mussels Facts

- Prey

- Plankton, waste and debris from water

- Group Behavior

- Beds (like reefs)

- Fun Fact

- A female zebra mussel can deposit 30,000 to 1,000,000 eggs each year!

- Estimated Population Size

- unknown

- Most Distinctive Feature

- Alternating dark and light stripes on outer shells

- Other Name(s)

- Dreissena polymorpha

- Gestation Period

- two days

- Habitat

- freshwater rivers, lakes and streams

- Predators

- Ducks, fish, crabs

- Diet

- Herbivore

- Type

- mollusk

- Common Name

- Zebra mussel

- Number Of Species

- 1

View all of the Zebra Mussels images!

Zebra mussels are small freshwater mollusks that look like tiny clams.

They usually measure only the size of a fingernail, up to one inch long. Their outer shell physical characteristics consist of bands of dark and light stripes, earning their name from the zebra.

Zebra mussels are the only freshwater mollusk species able to attach to hard surfaces. They originated in Eastern Europe’s Caspian Sea. Being an invasive species, they traveled in the tanked ballast water of ships and other marine vessels into waters throughout the world.

The mollusks invaded North America by way of the Great Lakes in Wisconsin in 1988. Since that time, they have been accidentally transported to bodies of water throughout 23 states of the United States, most likely on the hulls and equipment of watercraft like barges and by means of the Mississippi River.

Because a female zebra mussel can lay up to 1 million eggs per year, the species easily thrives where it gains entry. Their ability to attach to hard surfaces creates problems for urban infrastructure, such as water pipes and underwater electrical utilities. Wisconsin’s electrical utility has spent well over $1 million per year trying to keep its systems safe from the mussels.

5 Incredible Zebra Mussel Facts!

The zebra mussel was brought to the United States on ships and continues to colonize new areas.

©iStock.com/VitalisG

- Up to 700,000 zebra mussels have been found living in one square meter

- The mussel’s changes to the food web are as destructive to their habitats as toxins, nutrient pollution, and acid rain

- Zebra mussels cause millions of dollars of damage each year by attaching to drinking water intake pipes, power plant equipment, and other man-made structures

- The mollusks are moved from one water body to another by hitchhiking on barges, boats, boat trailers, seaplanes, and other watercraft

- The mussels first entered the United States through Lake Michigan in 1988, then were discovered in the Mississippi River by 1991

Evolution and Origins

The zebra mussel originally comes from Eastern Europe and Western Russia. It was brought into the Great Lakes of the United States by accident, as a result of contaminated ballast water being discharged from cargo ships.

Zebra mussels were first brought into North America’s Great Lakes in 1986 due to the release of polluted ballast water from cargo ships. Following their initial introduction in the Great Lakes, human activity has enabled zebra mussels to spread into other water bodies in eastern Canada and the USA.

Furthermore, during the Paleozoic era, over 245 million years ago, mussels are believed to have evolved from a marine bivalve ancestor. Evidence from fossil shells suggests that mussels lived alongside dinosaurs during the Mesozoic era, also known as the Age of Dinosaurs, which spanned from 65-245 million years ago.

Classification and Scientific Name

Peter Simon Pallas, a zoologist from Prussia, gave the scientific name Dreissena polymorpha to the zebra mussel in 1771.

©iStock.com/scubaluna

The zebra mussel, Dreissena polymorpha, was given its scientific name by Prussian zoologist Peter Simon Pallas in 1771. The freshwater marine creature belongs to the order Myida, superfamily Dreissenoidea, and family Dreissenidae. Dreissenidae is a family of small aquatic bivalve mollusks that attach themselves to hard surfaces.

Dreissena polymorpha is partly derived from the Greek word polymorphos, meaning “of many forms.” The genus Dreissena for which the zebra mussel is named is one of great debate between Russian and Western scientists.

The scientists differ greatly in their styles of species identification and categorization. But 7 species are typically listed as part of Dreissena worldwide, including the zebra mussel. Besides Dreissena polymorpha, only one other species commonly called the quagga mussel lives in the United States.

Appearance

Zebra mussels are tiny mollusks that share physical characteristics with clams. They are named for their bands of dark and light stripes on their shells, much like the pattern of a zebra. The interior of their shell is solid white. Most of these mollusks are less than 1 inch in length but specimens as large as 2 inches are frequently found.

Zebra mussels are a freshwater species, in fact, the only freshwater type able to attach to solid surfaces underwater. They make this attachment using byssal threads, strong, glue-like fibers on their bodies. Although their dark-light alternating shell stripes usually make the mussels easy to identify, their coloration can vary.

In the absence of clear stripes, defining physical characteristics include a dark hinge between the top and bottom shells and symmetry of the top and bottom shells. Other species of dreissena, such as Dreissena rostriformis bugensis have light hinges and asymmetry of the two shells.

Wherever zebra mussels establish a habitat, they are harmful and cause damage.

©scubaluna/Shutterstock.com

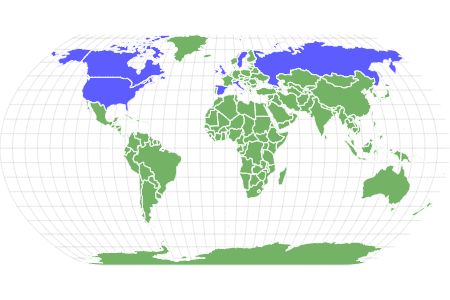

Distribution, Population, and Habitat

Zebra mussels are destructive wherever they invade and develop a habitat. In fact, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reported that these mollusks cause major changes in the hydraulic flow of rivers and lakes as observed in the Detroit River. This change in river flow happens because the zebra mussels attach to the river bottom and hard surfaces in the water, forming reefs.

Their presence also leads to sharp declines in freshwater shrimp-like organisms called Diporeia. Diporeia has high fat and calorie content, making them a key part of the marine food chain in America’s lakes and rivers, as it has been since 10,000 BC.

Then, because there are fewer Diporeia to eat, the mussels also relate to declining fish health. In Lake Ontario, lake trout populations dropped by 90 percent within eight years of the zebra mussels’ invasion. Fish species are also shown to grow 24% slower because of the lost nutrients occurring from the mussels’ presence.

Where to Find Zebra Mussels and How to Catch Them

Zebra mussels are heavily concentrated throughout Europe and Asia, where they have lived for hundreds of years. In the 19th century, the mollusks made their way into the United Kingdom’s freshwater tributaries. In 1988, they reached America and have since made their way into at least 23 U.S. states and are reproducing by the millions. According to the US Geological Survey’s known facts, zebra mussels are now in every state adjacent to the Great Lakes and Mississippi Rivers.

They are also in California, Colorado, Nebraska, South Dakota, Kansas, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and Oklahoma, states with rivers that connect to the Mississippi River. Because of their rapid invasion, high numbers, survival rates, and few predators, the IUCN Red List classifies the zebra mussel population as being of least concern.

Zebra mussels prefer slightly alkaline water that ranges in temperature from 68 degrees to 77 degrees Fahrenheit at 2 meters to 12 meters deep. They do not like shallower water because the waves make it difficult for them to survive, but have been found in water as deep as 60 meters.

Although you can find zebra mussels on the bottom and hard surfaces of many bodies of water, it is not advised to catch, eat or keep them as pets. They are edible but do not taste good. The mollusks do not have enough nutrients to serve as other pets’ food, either. They also filter feed in waters with lots of pollutants, absorbing those toxins into their bodies. This means they contain a high concentration of toxins not safe for people or animals to consume.

Instead of hunting for or catching zebra mussels, the governments of most nations advise doing what they can to fight their invasion. They recommend washing your boat or other watercraft with warm, soapy water after taking it out of the water. You should also never take water in a bucket, boat well, or tank from one body of water to another. Always empty water onto land to avoid accidentally transporting larvae.

Predators and Prey

Zebra mussels live best in plankton-rich water with high levels of calcium. They need calcium to make their shells. Calcium level also relates to the presence of hard surfaces on which they can attach. Although the mussel can slowly crawl to a new location, they prefer to find one spot and attach it there for as long as possible.

Drawing their nutrition from the water, they do not need to move unless it is necessary for survival. One of the key facts of their survival is that being stationary plays a big role in how their predators find them and also how they obtain their nutrients.

What eats a zebra mussel?

Scientists are still researching the food chain related to zebra mussels. But some of the animals that eat them include crabs, drumfish, river redhorse suckerfish, river carpsuckers, and smallmouth buffalo fish. Diving ducks and other waterfowl sometimes eat them, too.

Other species may occasionally feed on them. But the mussels do not taste good and contain too few nutrients to support a healthy fish diet. Humans should not eat zebra mussels because of their bad taste and the pollutants they absorb.

What does a zebra mussel eat?

Adult zebra mussels feed on plankton, waste, and debris. They filter it from the water in which they live, processing up to a liter each day. In essence, they filter the water through their bodies, keeping the nutrients they need and disposing of the material they do not. In polluted water, the toxins are also absorbed into their bodies.

Reproduction and Lifespan

Zebra mussels live for 2 to 5 years on average. By 2 years of age, they can reproduce. To do this, the female releases eggs into the water where the male releases sperm. One female can release up to 1 million eggs per year. A male can release up to 200 million sperm. After fertilization, an average of 500,000 eggs per meter hatch release larvae called veligers.

The surviving veligers travel on water currents and swim freely. Their developing calcium shells weigh enough at about 2 weeks to 3 weeks of age to enable them to settle on a hard underwater surface. About 10,000 young settlers each day are firmly attached to their chosen spot to continue growing into an adult. During this time and for the rest of their lives, they filter water and draw nutrients into their bodies.

The attachment involves the use of thread-like strands extending from their bodies, called byssal fibers. These fibers use a sticky substance like glue to keep them in place. Although they are firmly locked down, only about 95% of the young survive into adulthood.

Fishing And Cooking

Humans do not generally eat zebra mussels. They are nutrient-poor and contain a high concentration of pollutants from the water they filter through their bodies. They also do not taste good.

View all 14 animals that start with ZZebra Mussels FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Where are zebra mussels found?

Zebra mussels originated hundreds of years ago in Eastern Europe and Asia. They have spread throughout the European and Asian countries over centuries. In the 1800s, they infiltrated freshwater bodies of the United Kingdom. Only since 1988 have they been in the United States. But during the past few decades, the mussels have invaded at least 23 states.

Why are zebra mussels so bad?

This highly invasive species damages natural habitats, fish, and the overall ecosystem in which they live. They do this by changing how water flows because of the space they occupy and changes they make by forming reefs on the bottom of rivers, lakes, and streams. Their presence leads to the death of nutrient-dense fish prey called Diporeia. Without this food source and the plankton consumed by the mollusks, fish grow more slowly and suffer poor health.

How do zebra mussels affect the ecosystem?

Zebra mussels disrupt ecosystems in a multitude of ways. They disrupt the food web, damage the current and flow of water and lead to the early death of native species. These invaders even damage human urban infrastructure like underwater pipes and utilities, causing millions of dollars of economic loss each year.

Are zebra mussels harmful to humans?

Humans should not eat zebra mussels. The mollusks do not taste good and hold onto concentrated levels of toxins filtered from the water throughout their lifespan. By eating them, people do not receive the nutrients they need from food and at the same time take the toxins into their own systems.

Does anything eat zebra mussels?

Ducks, other waterfowl, fish, and crabs sometimes feed on zebra mussels. But the mussels do not contain enough nutrients to serve as a healthy food source. The pollutants concentrated in their bodies can also harm the health of the animals that eat them.

Can you swim with zebra mussels?

Zebra mussels do not swim, except as microscopic larvae. As they grow, these mollusks attach themselves to hard surfaces underwater. They remain stationary for most of their lives, only crawling to a new location in response to extreme environmental changes.

How do I get rid of zebra mussels?

You should always clean watercraft with warm, soapy water after taking it out of the river or lake. Never transport water from one river or lake into another body of water. Otherwise, avoid the mussels as much as possible to prevent accidental relocation and invasion. If your local government has a hotline for reporting the species, do so to aid in their location.

What impacts have the rapid growth of zebra mussels had?

Zebra mussels reproduce in huge numbers and more than 700,000 of the mollusks can live in one square meter of water. This enables them to create giant reefs with their bodies by attaching them to hard surfaces. Their presence kills important creatures in the food web, starving native fish and leading to the slow growth of natural species.

How were zebra mussels introduced in the united states?

Zebra mussels came into the U.S. by way of Lake Michigan, most likely as passengers in the ballast water of a ship from Europe or Asia. They arrived this way in 1988, then moving in the current and down the Mississippi River on other vessels to locations throughout the country.

How do zebra mussels reproduce?

Zebra mussel females release eggs into the water. Males then release sperm, fertilizing the eggs. Those eggs become free-swimming larvae in just 2 to 3 days. At 2 years of age, the young adult mussel can then reproduce.

What are zebra mussels?

Zebra mussels are an invasive species of mollusk that originated in Europe and Asia, then moved into the United Kingdom, other countries, and North America.

What do zebra mussels eat?

Zebra mussels eat plankton, waste, and debris. They filter this matter from the water in which they live, taking the water into their bodies and dispelling what they do not need.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- USGS / Accessed October 8, 2021

- USDA / Accessed October 8, 2021

- Wikipedia / Accessed October 8, 2021

- Minnesota Department of Natural Resources / Accessed October 8, 2021

- Texas Invasives / Accessed October 8, 2021

- National Park Service / Accessed October 8, 2021

- Lilly Center for Lakes and Streams / Accessed October 8, 2021

- University of Minnesota / Accessed October 8, 2021

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources / Accessed October 8, 2021

- US Fish & Wildlife Service / Accessed October 8, 2021

- Great Lakes Now / Accessed October 8, 2021

- Michigan Invasive Species / Accessed October 8, 2021

- Washington Ivasive Species Council / Accessed October 8, 2021

- Iowa Aquatic Invasive Species / Accessed October 8, 2021

- Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks / Accessed October 8, 2021

- Texas Parks & Wildlife / Accessed October 8, 2021

- New York Times / Accessed October 8, 2021