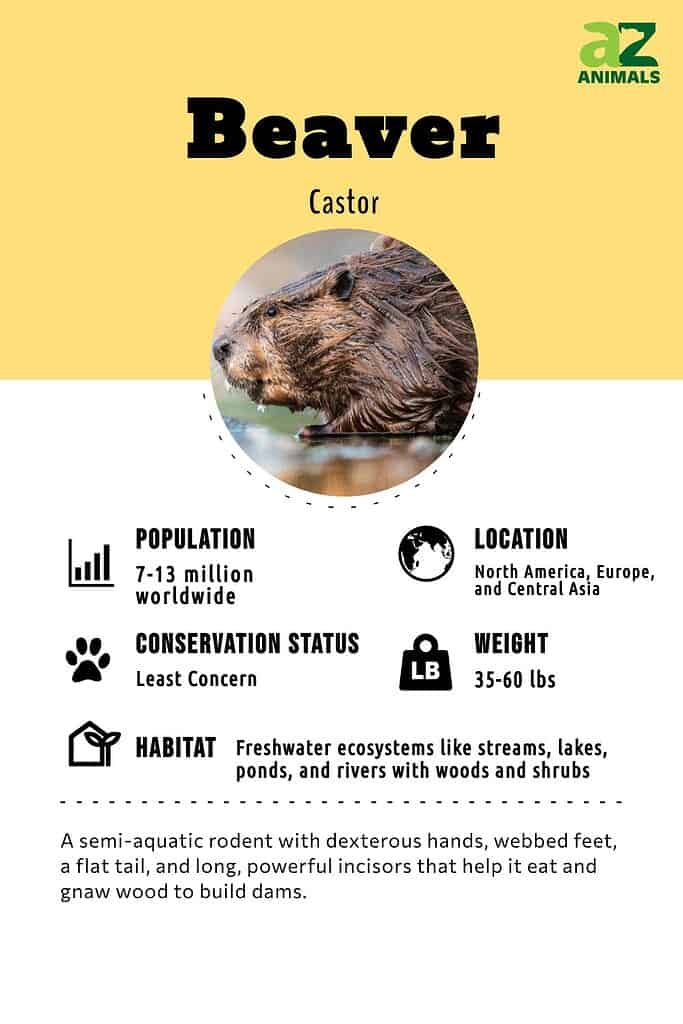

Beaver

Builds a dam from sticks and leaves!

Advertisement

Beaver Scientific Classification

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Beaver Conservation Status

Beaver Facts

- Average Litter Size

- 1-4

- Lifestyle

- Solitary

- Favorite Food

- Tree bark

- Type

- Mammal

- Slogan

- Builds a dam from sticks and leaves!

View all of the Beaver images!

The beaver dam is one of the great natural wonders of the animal kingdom.

A symbol of industry and work ethic, this semi-aquatic rodent can alter its surrounding landscape in order to shield itself from dangerous predators. Because the dam has beneficial effects on the rest of the environment, the beaver is considered to be a keystone species wherever it resides. That is why beaver populations have needed to recover after having been overhunted in previous centuries.

5 Incredible Beaver Facts!

- The name “beaver,” which entered the English language from early Germanic, can trace its roots back to a word meaning brown.

- The largest beaver dam ever found was about half a mile long in Alberta’s Wood Buffalo Park. It was thought to be a multi-generational project.

- The beaver first appears in the fossil record some 10 to 12 million years ago from Germany. It reached America from across the Bering Strait at least seven million years ago.

- The beaver is the national symbol of Canada.

- Beavers mate for life.

©Ghost Bear/Shutterstock.com

The 2 Types of Beavers

There are two main types of beavers inhabiting most parts of the Northern Hemisphere, which include:

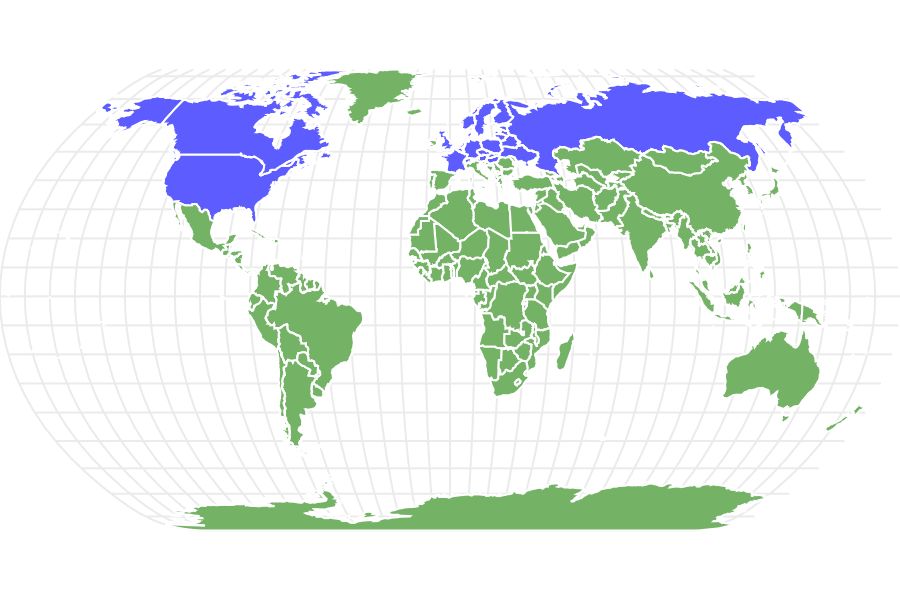

- North American Beaver – The North American beaver (Castor canadensis) is also referred to as the American beaver or Canadian beaver (of which it’s the national animal symbol). The American beaver has been introduced into Patagonia in South America and parts of Europe like Finland.

- Eurasian Beaver – The Eurasian (or European) beaver (Castor fiber) almost became extinct due to hunting for its fur and castoreum. Thanks to its being reintroduced in central Europe, Great Britain, Spain, Scandinavia, and parts of China and Mongolia, its population has bounced back.

Scientific Name

All living species of beavers belong to the genus Castor. This scientific name simply means beaver in Ancient Greek. There are two current species in the genus: the Eurasian beaver and the North American beaver, each of which can be further divided into various subspecies. Two more extinct species of this genus are known from the fossil record. One of these is Castor californicus, which lived in western North America and probably went extinct at some point in the Pleistocene (2.58 million years to 11,700 years ago). The second genus of beaver, known as the giant beaver, probably went extinct during the last Ice Age. As the name suggests, this massive creature grew up to 8 feet long and weighed 200 pounds. The beaver is the only living member of its family (scientific name Castoridae) and also belongs to the rodent order.

Evolution and History

The modern beaver is believed to have originated during the late Eocene Period in North America and crossed over the Bering Land Bridge in the early Oligocene Period, thus colonizing Eurasia. This would have happened 33 million years ago at a time when many animal species were going through changes. This time in history is referred to as the Eocene-Oligocene transition, or Grande Coupure, where mass amounts of life became extinct, mostly aquatic.

It was in the early Miocene period, approximately 24 million years ago, that castorids developed a semi-aquatic lifestyle. There were two types–giants like the Castoroidinae of North America and Trogontherium of Eurasia. From fossil evidence, researchers believe that Castoroidinae and modern beavers shared an ancestor which was a bark-eating animal. Bark-eating probably led to dam and lodge building so that these pre-historic beavers could survive winters in the subarctic.

Appearance

The beaver has a stout body, strong neck, oversized head, short and rounded ears, dexterous hands, webbed feet, and a flat tail. Its reddish dark brown waterproof fur is composed of two layers: a soft lower layer and stiffer protective upper layer. The beaver’s back foot has a specialized claw that functions as a comb for cleaning its fur.

The beaver has a unique adaptations to help it survive in its natural habitat. Its sharp incisors, which are fortified with iron and trace minerals (giving it an orange color), have a slight backward curve to aid it in cutting down trees. Its large, flat, leathery tail serves multiple purposes: it stores excess fat for the winter, provides a useful warning to others when slapped in the water, and braces the body against the ground as it chews into trees. When it’s submerged, the beaver’s ears, nose, nictitating membrane (an additional eyelid), and lips behind the teeth can all be closed off to prevent water from entering its body. Propelled by their hind feet, beavers can swim through the waters at around 5 mph.

The beaver’s sharp, orange incisors, fortified with iron and trace minerals, help it cut down trees with ease.

©U. Eisenlohr/Shutterstock.com

The beaver is the second-largest rodent in the world, the largest being the capybara. Head to rump, it can grow up to 4 feet long, with an additional 10 to 20 inches comprising the tail. The beaver is about the same size as a medium dog, weighing between 24 and 66 pounds.

The Eurasian and North American beavers are quite similar in appearance, but you can definitely notice some subtle differences between them. The North American species is slightly smaller in size. It also has a narrower head and a more oval-shaped tail. Despite people’s best efforts, the two species cannot be hybridized together, perhaps because they carry a different number of chromosomes.

Behavior

Like no other animal on the planet, the beaver marshals enormous resources to construct its signature dam. This engineering project usually takes place in the summer or early fall, when the beavers cut down trees and shrubs with their teeth and then transport the material in their mouths to the site of their house. They pile up the sticks in the direction of the water flow and then stuff them with grass and mud. Whenever there’s a leak or structural problem, the beaver will strive to repair it as quickly as possible.

Beavers build dams to create a sustainable aquatic environment in which they can build a lodge.

©Chase Dekker/Shutterstock.com

The purpose of the dam is to create a sustainable aquatic environment in which they can build a lodge. These elaborate homes serve as a kind of island fortress on the water. They have a central chamber and two underwater entrances that predators cannot access. But if for whatever reason, the beaver is unable or unwilling to construct a dam on the water, it still can live in a den near the bank for protection.

One of the more remarkable facts about these lodges is the way that they alter the flow and level of the surrounding water. According to National Geographic, they can increase the amount of open water, which reduces droughts and improves the viability of wetlands by up to 600%. Unfortunately, the beaver can become a nuisance by accidentally damming up human-made streams, which can cause unwanted flooding.

The life of the beaver revolves around small family groups of about eight closely related individuals (called colonies) that forage, build dams, and raise the young together. These family bonds are reinforced and strengthened by grooming and play. But beavers are as equally intolerant to outsiders as they are friendly toward family members. These territorial animals will aggressively defend their land from outside intruders. They mark their territories by creating conspicuous mud piles laced with secretions. Once a threat approaches, the beavers will slap their tails on the water, which serves as a warning to interlopers and a signal to family members nearby. If they are in particular danger, then the beavers will escape into the water and hide in their lodges.

Scent is an integral part of the beaver’s communication skills. They produce urine-based castoreum oil from their anal gland (which some say smells like musky vanilla) for the purpose of marking territory and identifying other beavers. They also mix this oil with their fur to make it waterproof. Verbal calls are not a huge part of their communicative repertoire, but they do make low groaning noises.

Beavers are rarely seen during the day except around the dusk hours. They accomplish almost everything at night when predators are less likely to spot them. Unlike many other mammals, beavers do not hibernate for the winter but instead prepare meticulously for the sparse winter months by building up fat stores and food caches.

Rather than hibernate, beavers prepare meticulously for the sparse winter months by building up fat stores and food caches.

©SERGEI BRIK/Shutterstock.com

Habitat

As the name suggests, the North American beaver has a massive range that extends through most of Canada, the United States, and parts of Mexico (it was also later introduced into Finland), while the range of the Eurasian beaver extends through parts of Europe (including the UK) and into Central Asia. They are found exclusively in freshwater ecosystems such as streams, lakes, ponds, and rivers with heavy woods and shrubs.

Diet

Beavers are herbivorous foragers that have specialized microorganisms in their gut to break down very tough cellulose from plant matter. To cope with the coldest parts of the year, the beaver may store their food below their lodge to last through the winter. Even if the water is frozen over, the beaver can still access the food stores without any problems.

What does the beaver eat?

The beaver’s diet varies by season. In the spring and summer months, the beaver feeds on leaves, grasses, sedges, roots, and herbs. During the fall and winter months, they switch primarily to bark and wooded plants. The North American beaver seems to favor poplar, beech, alder, maple, and aspen trees. This clever creature can create a canal leading from the food source back to the dam.

Predators and Threats

The beaver has been historically threatened by habitat loss and trapping. For many centuries they were hunted on an enormous scale for their fur, meat, and oil. After numbers declined in Europe, the beaver fur trade became an integral part of the colonial economy in the Americas and reached its height at some point in the 19th century, when more than 150,000 pelts were hunted a year. Since then, the decline of the fur trade has removed an enormous source of population pressure from the beaver, which has enabled it to recover.

What eats the beaver?

The beaver is commonly preyed upon by mountain lions, wolves, coyotes, foxes, eagles, and even sometimes bears. But the loss of some predator populations has made it easier for the beaver to survive in the wild.

Reproduction, Babies, and Lifespan

The beaver is known as a faithful partner that will form exceptionally strong long-term monogamous relationships with a single mate. If its mate dies, only then will the surviving mate seek out another partner. However, a 2009 genetic study revealed some unusual facts about the beaver’s reproductive strategy. Much like humans, they may also engage in promiscuous short-term relationships whenever the opportunity arises. Beavers mate once every year between January and March in northern climates and between November and December in warmer climates. The female will prepare to give birth by creating a soft bed in the lodge, where she uses her tail as a birthing mat.

After a gestation period of around three months, the mother produces a litter of one to four kits at a time. These kits are born with a full coat of fur, open eyes, and the ability to swim. They receive thorough education (as well as protection) from both parents to prepare them for the rigors of adulthood. After about three more months, they are weaned by their mother and begin to rely fully on solid food. Most young stay with their parents for the first two years of life (to help with infant care and dam building) and then become sexually mature the year after. Beavers have a life expectancy of about 10 to 20 years in the wild.

By nature, the beaver is a faithful partner that will form a strong long-term monogamous relationship with a single mate.

©Telly/Shutterstock.com

Population

According to the IUCN Red List, both the Eurasian beaver and the North American beaver are considered to be species of least concern. It is estimated that six to 12 million beavers live in North America and another million in Europe. By the turn of the 20th century, after many years of heavy hunting, the beaver had disappeared from many parts of its former territory. Numbers have improved since hunting ceased, but they are not yet back to their former height.

Beavers in the Zoo

The beaver can be found at the Detroit Zoo, the Oregon Zoo, the Smithsonian’s National Zoo in Washington DC, the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago, the Minnesota Zoo, and elsewhere throughout the country.

View all 284 animals that start with BBeaver FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Are Beavers herbivores, carnivores, or omnivores?

Beavers are Herbivores, meaning they eat plants.

What Kingdom do Beavers belong to?

Beavers belong to the Kingdom Animalia.

What class do Beavers belong to?

Beavers belong to the class Mammalia.

What phylum to Beavers belong to?

Beavers belong to the phylum Chordata.

What family do Beavers belong to?

Beavers belong to the family Castoridae.

What order do Beavers belong to?

Beavers belong to the order Rodentia.

What type of covering do Beavers have?

Beavers are covered in fur.

What genus do Beavers belong to?

Beavers belong to the genus Castor.

In what type of habitat do Beavers live?

Beavers live in arid forests and deserts.

What is the main prey for Beavers?

Beavers eat tree bark, willow, and water lilies.

What are some predators of Beavers?

Predators of Beavers include wolves, bears, and lynx.

What are some distinguishing features of Beavers?

Beavers have transparent eyelids and a big, flat tail.

How many babies do Beavers have?

The average number of babies a Beaver has is 4.

What is an interesting fact about Beavers?

Beavers build dams from sticks and leaves!

What is the lifespan of a Beaver?

Beavers can live for 15 to 20 years.

Are beavers dangerous to humans?

No, beavers are not a direct danger to people, but their dams can cause flooding in some residential areas.

What does a beaver get eaten by?

The beaver is eaten by mountain lions, wolves, coyotes, foxes, eagles, and bears.

Can I have a pet beaver?

Because of their wild nature and very specific habitat and dietary requirements, the beaver would not adapt very well at all to a domestic human existence. However, if a beaver cannot be returned to the wild, then some wildlife experts who know how to deal with the beaver’s needs may keep one in captivity.

Where are beavers found?

Beavers are found all over North America, Europe, and even parts of Central Asia.

How big are beavers?

The beaver can grow up to 47 inches from head to rump and another 20 inches or so with the tail included. It also weighs up to 66 pounds in size.

What are the differences between beavers and woodchucks?

Beavers are a different species than woodchucks. They are also adapted for swimming, while woodchucks are adapted for digging holes in dirt.

What is the difference between a beaver and a groundhog?

The greatest differences between a beaver and a groundhog lie in their size, habitat, and diet. Beavers are larger than groundhogs by a significant amount, although groundhogs are likely the largest marmots in the world. Additionally, the habitat that the two live in is drastically different. Beavers are semi-aquatic animals that require a water source to live, while groundhogs are terrestrial animals that mostly live in underground burrows. Finally, the diets of a beaver and a groundhog are different. Beavers are famous for their woody appetites and eat the inner bark of a variety of trees. Groundhogs eat mostly grasses, flowers, shrubs, and crops.

What is the difference between a platypus and a beaver?

The greatest differences between a platypus and beaver lie in their size, morphology, and reproduction. Beavers are far larger than platypuses, weighing over 10 times as much and doubling their overall length.

What is the difference between a marmot and a beaver?

The key differences between marmots and beavers are their habitat and shelter type, level of winter activity, diet, and physical traits of size, coat, and tail. Their communication also differs, as they have different vocalizations in response to threats.

What is the difference between a gopher and a beaver?

The key differences between gophers and beavers are their size, appearance, habitat, lifespan, diet, habits, and physical features.

How to say Beaver in ...

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- National Geographic / Accessed February 6, 2021

- Animal Diversity Web / Accessed February 6, 2021

- Science Focus / Accessed February 6, 2021