Brown Headed Cowbird

Molothrus ater

Males are generally monogamous during mating season and will protect the female from other males. However, females tend to venture from their partners and mate with other males.

Advertisement

Brown Headed Cowbird Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Aves

- Order

- Passeriformes

- Family

- Icteridae

- Genus

- Molothrus

- Scientific Name

- Molothrus ater

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Brown Headed Cowbird Conservation Status

Brown Headed Cowbird Facts

- Prey

- Spiders, grasshoppers, and beetles

- Name Of Young

- Chicks

- Group Behavior

- Solitary/Pairs

- Pair

- Fun Fact

- Males are generally monogamous during mating season and will protect the female from other males. However, females tend to venture from their partners and mate with other males.

- Estimated Population Size

- 56 million individuals

- Biggest Threat

- Birds of prey

- Most Distinctive Feature

- Brown head

- Wingspan

- 12.6 to 15 inches

- Incubation Period

- 10 to 12 days

- Age Of Independence

- 25 to 39 days

- Age Of Fledgling

- 10 to 11 days

- Habitat

- Grasslands with low, scattered trees, the edges of woodlands, prairies, pastures, brushy thickets, fields, orchards, and residential areas.

- Predators

- Broad-winged Hawks, Barred owls, Northern goshawks, Cooper's hawks, Sharp-shinned hawks, Northern saw-whet owls, Blue jays, and Northern flying squirrels

- Diet

- Omnivore

- Favorite Food

- Grains

- Common Name

- Brown-headed cowbird

- Origin

- Norht America

Brown Headed Cowbird Physical Characteristics

- Color

- Brown

- Black

- White

- Green

- Multi-colored

- Skin Type

- Feathers

- Lifespan

- 16 years

- Weight

- 1.3 to 1.6 ounces

- Length

- 12.6 to 15 inches

- Age of Weaning

- 25 to 39 days

- Venomous

- No

- Aggression

- Medium

View all of the Brown Headed Cowbird images!

The brown-headed cowbird is a stumpy blackbird with a peculiar way of parenting. They accept no responsibility for raising their young.

Instead of building nests, females spend all their time and energy laying eggs. They can lay up to 36 eggs over the summer period. However, they lay these eggs in other birds’ nests and fly off without a second glance. Unfortunately, this typically comes at the expense of a few of the host’s own chicks.

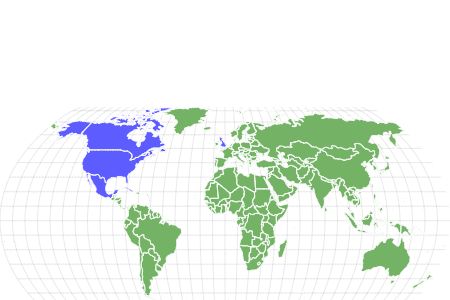

Brown-headed cowbirds originated from the open grasslands of North America but have since spread to South America and landed in places like the United Kingdom and Belize through human trade.

Three Incredible Brown-Headed Cowbird Facts!

- Brown-headed cowbird males are monogamous, but the females mate outside of their pairing

- They live up to their name because cowbirds control the insect population in the cow’s habitat

- Brown-headed cowbirds make various sounds, including clicking, whistling, and chattering. Females use their distinctive rolling chatter to attract males.

Where to Find the Brown-Headed Cowbird

Brown-headed cowbirds are native to the temperate regions of North America, but in winter, they migrate to the southern regions of the USA and Mexico. Humans have caught them and traded them as pets and show pieces, so now they also inhabit these countries and islands:

- Bahamas

- Canada

- Cuba

- Saint Pierre and Miquelon

- Turks and Caicos

- Belize

- United Kingdom

Habitat

Brown-headed cowbirds are highly adaptable and inhabit grasslands with low, scattered trees, the edges of woodlands, prairies, pastures, brushy thickets, fields, orchards, and residential areas.

One habitat that they tend to avoid is forests. Unlike other bird species, the brown-headed cowbird population has thrived in fragmented forests in the eastern United States.

During winter, they will roost among multiple species of blackbirds in big flocks of over 100,000 birds.

Nests

Brown-headed cowbirds do not build nests; instead, the females lay their eggs in other birds’ nests and expect them to raise their young. Unfortunately, this typically comes at the expense of the host’s own chicks. Their clutch size is generally between 1-7 eggs, and they can lay over 36 eggs over a summer.

Brown-Headed Cowbird Scientific Name

The brown-headed cowbird’s scientific name is Molothrus ater, which means “dull black” in Latin. These birds belong to the Order Passeriformes, Latin for “sparrow-shaped,” and include most of the bird species.

Passeriformes are often referred to as perching birds and identified by their unique toes, with three pointing forward and one back. This toe arrangement helps with perching.

Brown-headed cowbirds are members of the Family Icteridae, also known as New World blackbirds. They are colorful small to medium-sized birds, and most species have predominantly black plumage with patches of yellow, red, or orange. However, each species differentiates in size, behavior, shape, and coloration.

There are only three recognized subspecies, and they include:

- M. a. ater – found in southeast Canada, northeast Mexico, and east and central USA

- M. a. artemisiae – found in west USA and west Canada

- M. a. obscurus – found in coastal Alaska, USA, Canada, and northwest Mexico

Size and Appearance

The brown-headed cowbird is a stumpy blackbird with a peculiar way of parenting. They accept no responsibility for raising their young.

©Jeff W. Jarrett/Shutterstock.com

Brown-headed cowbirds are approximately 6.3 to 7.9 inches in length and weigh between 1.3 to 1.6 ounces. In addition, their wingspan ranges between 12.6 to 15 inches.

They are small, stocky, and compact with a short, thick-based bill, very similar to the finch. Brown-headed cowbirds are primarily seen foraging on the ground with their tails cocked.

Adult males have a glossy black body with a greenish sheen, contrasting with their brown heads. They have dark eyes and black bills and legs.

Mature females are mainly dull brown, with dark wings and tails, and their inner flight feathers have crisp pale fringes. They have dark eyes with pale areas below the eyes. In addition, they have a whitish throat, contrasting their darker faces. They also have obscure streaking on their underparts, with a dark bill and legs.

Juveniles look similar to the females but have darker streaking and paler feather fringes.

Migration Pattern and Timing

Cowbirds are short-distance migrants and typically remain on the North American continent. However, during winter, they migrate to the southern States and Mexico’s northern regions.

During the colder months, they will join large flacks consisting of multiple species of blackbirds like the red-winged blackbirds and Brewer’s blackbird.

Behavior, Reproduction, and Molting

Brown-headed cowbirds generally forage on the ground between flocks of starlings, grackles, and other blackbirds. They benefit from their close association with grazers like bison and cows, hence the name. These grazers flush up insects when eating, and the cowbirds swoop down to claim their meal.

To attract females, males will sing and raise their chest and back feathers while lifting their wings and spreading their tail feathers, and lastly, they bow forward. The males will sometimes do this together in a group.

The females don’t build nests or take care of their young. Instead, they watch quietly until they find other birds building nests; they may even flutter through dense vegetation, flushing birds from their nests. Once the brown-headed cowbird has found a suitable nest, she often kicks out the host bird’s egg/eggs to make room for her own.

Diet

These birds are foragers and generally look for food on the ground of open grasslands. They are usually found near herds of livestock like cows, which flush up insects when they graze. These insects include:

- Spiders

- Leafhoppers

- Grasshoppers

- Beetles

However, they are omnivores, and most of their diet consists of plant matter, including seeds and fruit. Interestingly, during mating season, females will eat snail shells, which increases their calcium level, and helps egg production.

In addition, both the males and females eat other birds’ eggs. However, during winter, their food of preference Is grains.

Reproduction

Brown-headed cowbirds have an average clutch size o 1 to 7 eggs and an incubation period of 10 to 12 days. In addition, their nesting period lasts for 8 to 13 days.

Females are the ones who choose a mate, and the males try to impress them with exciting displays and perched songs. During their mating ritual, the males will fluff their feathers, spread their wings and tails, and bow down to their potential mates.

The females select a male based on their song spreads and flight whistle performance. Brown-headed cowbirds are generally monogamous, forming life-long pairs. However, mating systems can vary depending on the population.

It is not unusual for many populations to have more males than females, which gives the females the opportunity to be picky when choosing a mate.

Males are generally monogamous during mating season and will protect the female from other males. However, females tend to venture from their partners and mate with other males.

Unfortunately, males do not offer females food, protection from predators, nesting resources, or help raise their young, which means there is no benefit for the females to be monogamous.

Nomadic males (not in a pair) sometimes mate with unguarded females, mainly when their mate is out foraging. Generally, females with bigger territories are more likely to breed outside their pair.

Mating Season

Brown-headed cowbirds’ mating season can begin as early as mid-April and ends as late as August; however, their egg-laying season usually occurs from May to June.

Brown-headed cowbirds can lay various amounts of eggs during mating season and may even lay over 36 eggs over the summer. However, the number of eggs they lay per season depends solely on how many host nests are available.

Females don’t waste time when it comes to laying eggs to avoid being caught by the hosts of the nest. It takes them as little as 41 seconds compared to other passerines, who take between 20.7 to 103 minutes to lay an egg.

It takes their eggs 10 to 12 days to hatch, which usually allows them to hatch before the host’s eggs, which means they get plenty of food and time to grow before the host’s hatchlings.

In addition, the brown-headed cowbirds beg excessively, making the host parents feed them more than their own offspring. This helps the cowbirds outcompete the host’s hatchlings, often causing the death of one or all of the host’s offspring.

Brown-headed cowbird fledglings generally leave the nest after 10 to 11 days and are entirely independent of their host parents at 25 to 39 days. Once independent, they find a flock of other brown-headed cowbirds to join.

Lifespan

Brown-headed cowbirds can live for a long time, with the oldest living cowbird making it to 16.9 years.

Predators, Threats, and Conservation Status

The brown-headed cowbirds’ eggs make a good meal for red squirrels, blue jays, northern flying squirrels, and yellow-bellied sapsuckers. Adults are also vulnerable, and their predators include:

- Broad-winged hawks

- Barred owls

- Northern goshawks

- Cooper’s hawks

- Sharp-shinned hawks

- Northern saw-whet owls

- Blue jays

- Northern flying squirrels

Unlike most bird species, brown-headed cowbirds thrive from human activities like farming, urbanization, and deforestation. However, their population numbers are decreasing. But, as for now, they are still listed as Least Concern on the IUCN’s Redlist.

Population

The brow-headed cowbird has an estimated population of around 56 million individuals and an average breeding population of 120 million individuals. However, their North American populations have slightly declined over the past 40 years.

How do Brown-Headed Cowbirds Communicate with Each Other?

Brown-headed cowbirds make a variety of calls, including:

- Single-syllable calls

- Flight whistles

- Keks

- Perched songs

- Chucks

- Chatter

The purpose of these vocalizations is for courtship, aggression, threats, species and individual identification, and alerts.

They are clever little birds that learn these calls through learning after leaving their host parent’s nests. Even though they are raised by different species, they do not embrace the said species’ songs. This is a unique capability as most other songbirds must be taught their songs.

There is minimal difference between calls made in different populations, but there are variations between individuals.

Different Calls

Flight whistles are used exclusively by males as a form of long-distance communication, which consists of pure tones. These whistles often include trills and are primarily vocalized before or during flight or five seconds before mating. In addition, flight whistles can also be used as an alarm call.

Males use single-syllable calls that consist of a single pure tone. They generally have 1 or two rings, used similarly to flight whistles, but are vocalized more often when other members of the same species are around.

Brown-headed cowbirds males are the only ones who use perched songs, and they have a frequency of 0.5 to 12kHz, the widest range of any bird song.

Males have one to eight different perched songs, and they use them during courtship, along with song-spread displays of puffing up their breast and back feathers and spreading their wings and tails. In addition, they are used as acts of aggression between males and identification and establishment of social hierarchies.

Chucks or keks are abrupt notes used by both males and females. However, these notes can only be detected up to 5 m of the cowbird. So, unfortunately, there is not much research about these vocalizations.

Chatter is mainly used by females and sometimes as a response to other calls. While there are minimal differences in chatter between subspecies or populations, there are variations between individuals. This leads researchers to believe these sounds are used for identification.

What Roles do Brown-Headed Cowbirds have In the Ecosystem?

Because brown-headed cowbirds are brood parasites, their mating habits affect several other species. They impact 226 different host species that vary in size, from stocky blackbirds weighing over 3.5 ounces to warblers weighing only 0.3 to 0.5 ounces.

However, out of these 226 species, they only parasitize 132 species, primarily:

- Yellow warblers

- Red-eyed vireos

- Song sparrows

- Wood thrushes

- Common yellowthroats

Brown-headed cowbirds are one of the causes of population decreases in multiple host species because they damage or eat their eggs, and their offspring outcompetes the host’s hatchlings. In addition, many hosts abandon parasitized nests.

Because of this behavior, brown-headed cowbirds are seen as a threat to a few endangered species. So, to control their population, culling programs have been introduced. These programs illuminate thousands of cowbirds each year to allow host populations to increase.

Culling programs are enforced to protect:

- Kirtland’s warblers

- Least bell’s vireos

- Black-capped vireos

- Southwestern willow flycatchers

Similar Animals

View all 282 animals that start with BBrown Headed Cowbird FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Are brown-headed cowbirds rare?

Unlike most bird species, brown-headed cowbirds thrive from human activities like farming, urbanization, and deforestation. However, their population numbers are decreasing. But, as for now, they are still listed as Least Concern on the IUCN’s Redlist.

Are brown-headed cowbirds invasive?

Because brown-headed cowbirds are brood parasites, their mating habits affect several other species. They impact 226 different host species that vary in size, from stocky blackbirds weighing over 3.5 ounces to warblers weighing only 0.3 to 0.5 ounces.

Why is it called brown-headed cowbird?

• They live up to their name because cowbirds associate closely with livestock (primarily cows) and eat the insects that jump up while they graze.

Do cowbirds eat other birds eggs?

Yes, brown-headed cowbirds eat eggs from other bird species.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- IUCN Redlist / Accessed August 14, 2022

- Wikipedia / Accessed August 14, 2022

- All About Birds / Accessed August 14, 2022

- Audubon / Accessed August 14, 2022

- Celebrate Urban Birds / Accessed August 14, 2022

- Mass Audubon / Accessed August 14, 2022

- Nest Watch / Accessed August 14, 2022