Viper

Vipers are one of the most widespread groups of snakes and inhabit most

Advertisement

Viper Scientific Classification

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Viper Conservation Status

Viper Facts

- Prey

- Rodents, bats, birds, lizards, frogs, scorpions

- Main Prey

- Rodents

- Name Of Young

- Neonate or snakelet

- Group Behavior

- Solitary

- Solitary except during mating season

- Communal Dens

- Fun Fact

- Vipers are one of the most widespread groups of snakes and inhabit most

- Estimated Population Size

- Widespread

- Biggest Threat

- Habitat destruction and people killing them out of fear

- Most Distinctive Feature

- Hollow fangs that fold up into the mouth

- Other Name(s)

- viper, asp, adder

- Age Of Independence

- Birth

- Litter Size

- 5-50

- Lifestyle

- Crepuscular

- Diurnal/Nocturnal

- Common Name

- viper, adder, asp

- Special Features

- Keeled scales, large bodies

- Location

- Asia, Europe, Africa

Viper Physical Characteristics

- Color

- Brown

- Grey

- Yellow

- Fawn

- Red

- Black

- White

- Tan

- Green

- Brindle

- Dark Brown

- Cream

- Orange

- Chocolate

- Caramel

- Olive

- Beige

- Skin Type

- Scales

- Lifespan

- 10+ years

- Length

- 1-7 feet long

- Age of Sexual Maturity

- 2+ years

- Venomous

- Yes

- Aggression

- Medium

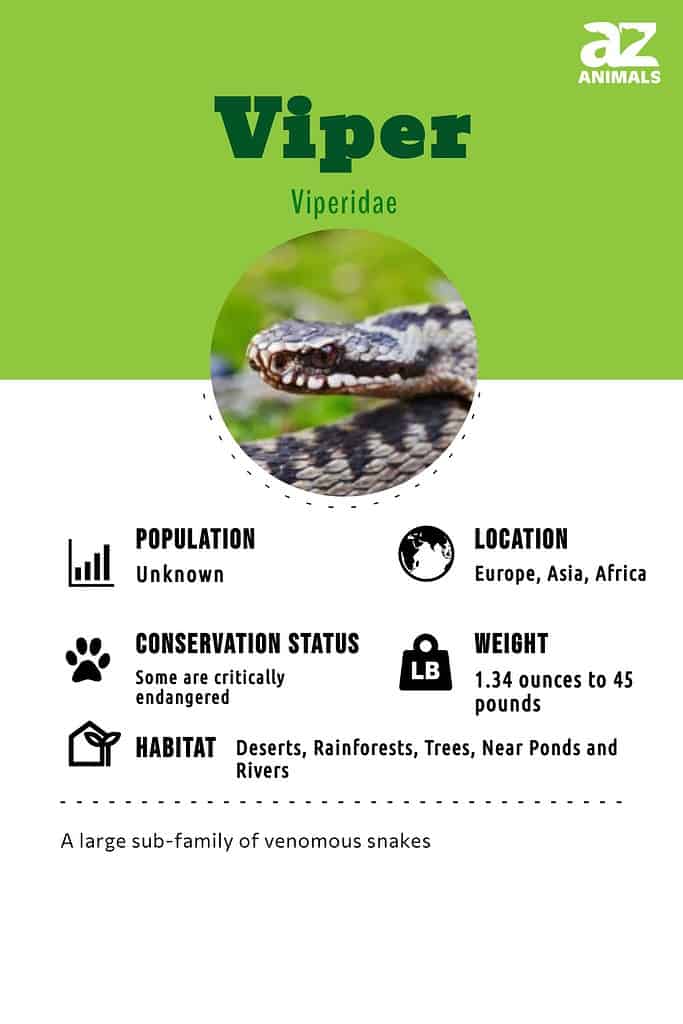

Vipers are a large subfamily of venomous snakes in the Viperidae family of the class Reptilia.

They inhabit most of continental Europe, Asia, and Africa and are responsible for a large number of snakebites in those areas. Vipers are diverse and highly evolved, with retractable fangs and large venom glands.

Incredible Facts About Vipers

- There are over 60 viper species, and all of them have fangs that fold up into the mouth.

- Vipers have keeled scales that help with camouflage.

- They do not have heat-sensing pits, but a few seem able to respond to thermal cues.

- They give birth to their young instead of laying eggs.

- Vipers are an Old World group of snakes, meaning that they do not live in the Americas. Instead, they live in Africa, Asia, and Europe.

Scientific Name and Classification

Vipers are old-world snakes from Europe, Asia, and Africa.

©Mark_Kostich/Shutterstock.com

True vipers are in the Viperinae subfamily of Viperidae. The Viperidae family includes four subfamilies: Azemiopinae, Causinae, Viperinae, and Crotalinae.

Each subfamily has something that sets it apart from the others. Crotalinae are pit vipers, like western diamondback rattlesnakes and golden lanceheads. They are born, not hatched from eggs, and their fangs are quite long and have a hinging action that erects them attached to large venom glands behind the eyes.

Causinae only has one genus and a few species. Now, it depends on which source you quote on whether they’re meant for their own subfamily or they should be in the Viperinae subfamily. There are arguments for both. They’re unique in that they lay eggs. Their fangs and venom glands are also different. The fangs don’t hinge, but the upper maxillary bone moves instead, and the front of the fangs aren’t entirely closed, hypodermic needle-style.

The other single genus subfamily is Azemiopinae; these are also egg layers. This subfamily is considered a primitive form of the viper. Their fangs are quite small, but they do rotate into place. Their heads are covered with large shield-shaped scales, like colubrids, and their dorsal scales are smooth.

Those in the Viperinae subfamily are considered true vipers. They are also called pitless vipers, true adders, and Old World vipers. They give live birth and have fangs that fold up into their mouths that are attached to large venom glands, but they don’t have heat-sensing pits.

Types of Viper

African bush vipers are one species of the Atheris genus.

©iStock.com/Mark Kostich

With a large subfamily like Viperinae, there are dozens of snakes to see. There are about 13 genera and over 60 species of viper. To give you an idea, the following list includes a selection of snakes from each genus.

Bush Vipers (Atheris)

The Atheris genus includes 16 species of bush vipers, and there are a few that look like something out of a movie or comic book. They’re generally slender and arboreal, preferring birds to mice.

- Spiny bush viper (Atheris hispida)

- Eyelash bush viper (Atheris ceratophora)

- West African bush viper (Atheris clorechis)

- Mount Kenya bush viper (Atheris desaixi)

Puff Adders (Bitis)

Puff adders warn predators with loud hissing and puffing up their bodies.

©iStock.com/EcoPic

The puff adders puff their body up and hiss loudly to warn away threats, but their hiss sometimes sounds more like a growl. There are 15 puff adder species, and they’re all highly venomous.

- Gabon viper (B. gabonica)

- Horned adder (B. caudalis)

- Peringuey’s desert adder (B. peringueyi)

- Puff adder (B. arietans)

- Rhino viper (B. nasicornis)

Horned Vipers (Cerastes)

This genus holds those vipers with horns over their eyes. The horns are made from one protruding scale and protects their eyes from the dust of the desert landscape where they live.

- Desert horned viper (Cerastes cerastes)

- Sahara sand viper (C. viperus)

- Gasperetti Arabian horned viper (C. gasperettii)

Day Adders (Daboia)

This genus, until recently, only had one species recognized. However, newer research has shown that there are, in fact, four species of day adder. Russel’s viper is one of the biggest causes of snakebites in India. These snakes seem to have nerve bundles in their snouts that help them respond to thermal cues – even without pits.

- Moorish viper (D. mauritanica)

- Palestine viper (D. palaestinae)

- Russel’s viper (D. russelii)

- Eastern Russel’s viper (D. siamensis)

Carpet Vipers (Echis)

Carpet vipers are so named because their strongly keeled scales and color patterns are reminiscent of a shaggy carpet. They are highly venomous and native to parts of North Africa, the Indian subcontinent, and West Asia. The Saw-scaled viper is one of the “Big Four” in India for snakebite occurrences.

McMahon’s Viper (Eristicophis mcmahoni)

This monotypic genus only includes one species that inhabits a desert region of Balochistan, near the border of Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.

Large Palearctic Vipers (Macrovipera)

The blunt-nosed viper (M. lebetinus), Razi’s viper (M. razii), and Milos viper (M. schweizeri) are large vipers that are found in the steppes and semideserts of northern Africa, Near and Middle East, and the Milos Archipelago in the Aegean Sea.

Mountain vipers (Montivipera)

There are eight currently accepted species in the Montivipera genus. They occur in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkey, Iran, and Iraq. They include the critically endangered ocellate mountain viper (M. wagneri), Armenian viper (M. raddei), and the very aggressive Ottoman viper (M. xanthina). Most of these snakes reach close to four feet long. Several mountain viper species are at the St. Louis Zoo and others, and are included in Species Survival Plans that help prevent the extinction of the species

Lowland viper (Proatheris superciliaris)

Scientists created the monotypic genus Proatheris just for this snake. It’s native to East Africa and inhabits wet, marshy areas, staying close to the rodents’ burrows. It is quite small and only reaches about 24 inches long at its longest.

False-horned Vipers (Pseudocerastes)

These snakes look like they have horns, but a true horned viper’s horn consists of only one scale – not the several scales that look like horns in the Pseudocerastes genus. Currently, there are three species recognized, including the Persian horned viper (P. persicus), Spider-Tailed horned viper (P. urarachnoides), and Field’s horned viper (P. fieldi). They occur in areas from the Sinai of Egypt to Pakistan.

Vipers (Vipera)

The Vipera genus has the most species of any genus in Viperinae, with 21 snakes that inhabit Great Britan and nearly all of continental Europe. Several, including the Common adder (V. berus), even range as far north as the Arctic Circle.

Evolution and Origins

Mangrove Pit Viper

©Kurit afshen/Shutterstock.com

Vipers are a species of venomous snakes that have two large, mobile fangs. This family of snakes has been around for more than 50 million years and has been divided into three subgroups. These snakes have developed several unique traits, such as heat-sensitive pits and sound-producing rattles. Vipers live in many different habitats and are able to eat large, bulky prey. Unfortunately, many of these species are endangered, and there is still much to discover about their evolution.

Humans have identified three types of venomous snakes that evolved to have front fangs. These snakes are categorized in the family Viperidae and include the subfamilies Viperinae, Azemiopinae, and Crotalinae. Fossils of vipers dating back to the lower Miocene have been found, but recent studies suggest that they may have originated much earlier in the early Eocene.

Vipers originated in the Old World and eventually spread to North, Central, and South America. Along with their specialized venom delivery system, certain features emerged in the process of evolution, like the loreal pits of pitvipers and the rattle of rattlesnakes. These distinguishing characteristics enabled vipers to occupy a variety of habitats.

Vipers have evolved to feed on a variety of things, ranging from generalists to those that specialize in certain prey, like lizards, mammals, birds, and frogs. Additionally, some lineages of vipers have developed behaviors such as arboreal habits, nocturnal and diurnal activity, and different reproductive modes.

Appearance and Behavior

A close-up of a nosed-horned viper. The most noticeable thing about this snake is the fleshy horn atop its snout.

©taviphoto/Shutterstock.com

In general, vipers in the Viperinae subfamily have stout bodies, hinged fangs that tuck up into the mouth, large venom glands, and keeled scales; and they are obligate carnivores. This is where the similarities end. Vipers vary widely in appearance, markings, colors, sizes, and habitats. For example, the spiny bush viper is arboreal and looks like a tiny, legless dragon; in fact, one of its common names is the dragon viper. It almost never leaves the trees and can even mate high up off the ground. On the other end of the spectrum is the Gaboon viper, with its fat body and heavy camouflage. They are completely terrestrial, and many snakebites inflicted by the Gaboon viper happen because this snake is nearly impossible to spot. It relies on its fantastic camouflage for both hunting and hiding.

These snakes are generally solitary predators, except during mating season. In some areas, snakes den together, as with the common European adder in the northern latitudes. Denning together helps them keep from freezing to death during cold winters.

Most vipers are ambush predators and don’t actively forage. However, in areas where prey is scarce or more difficult to reach (in the trees, for example), many species actively forage. Others, like the spider-tailed horned viper, take a different approach altogether and use their tails to lure their prey to them.

Venom

An aggressive male nose-horned viper on a rock ( Vipera ammodytes ). Males have a background of gray or brown scales with a pattern of dark brown or black zigzags running down their backs.

©iStock.com/taviphoto

Strictly speaking, vipers are venomous and not poisonous. If that’s confusing, it’s okay because the two words get tossed around interchangeably. However, the difference is pretty straightforward and is in how the toxins get into the body. An animal like the cane toad is poisonous because the toxins get either ingested via eating or by being absorbed into the skin. Venom, on the other hand, is forcibly injected. So, a scorpion is venomous, and so is a nose-horned viper because they inject toxins into their victim.

According to a study published in Toxicology, most snakebites in Europe are caused by those from the Vipera genus, which includes the common European adder and the asp.

Typically, a viper’s venom is hemotoxic and acts on the blood and tissue of its victim. Some have highly toxic venom, but in other species, it is relatively mild. Some of the symptoms of envenomation can include pain and swelling at the bite, drops in blood pressure and heart rate, and issues with blood clotting. Depending upon the species, there may be many more symptoms, but regardless, it’s vital to get medical care immediately.

Habitat and Diet

Gaboon Viper eating a big rat. This is the heaviest venomous snake on the African continent.

©frantic00/Shutterstock.com

Vipers are a diverse group of animals with a wide range of adaptations depending on their habitat. These snakes have evolved differently to suit many habitats. As a result, vipers have managed to find ecological niches in most areas of Europe, Asia, and Africa. They live in habitats ranging from dry, sparsely populated deserts to lush rainforests with rivers, lakes, and ponds. A few, like Russel’s viper, live in and around human settlements or cities. Some, like the desert horned viper, evolved an extra scale above their eyes to protect their eyes from the desert sand. Then there’s the spiny bush viper. It’s arboreal and has a prehensile tail to hang from tree branches.

What all of these vipers have in common is the fact that they almost always exist on a diet of rodents, birds, bats, lizards, frogs, and sometimes other snakes. The neonates of some species may be small enough that they initially eat arthropods like scorpions or beetles.

Predators, Threats, and Conservation

Mongooses and birds of prey eat young vipers.

©MartinJGruber/Shutterstock.com

Many young vipers, or simply smaller individuals, are preyed upon by other carnivores. Birds of prey and mongooses are common threats. Sometimes herons and storks also prey upon vipers.

People are another threat to many species. These snakes are often feared because of the danger they can pose to an unsuspecting person. In some parts of the world, many deaths every year are caused by viper bites. So, the fear isn’t completely unwarranted. However, education seems to help humans live side by side with these beautiful but dangerous reptiles.

With some species, like the mountain vipers of the Montivipera genus, it’s not so much the fear but the rarity. They have become critically endangered because they are already smaller in number, and that natural rarity combined with their beauty makes them attractive to collectors. As a result, their wild numbers are greatly reduced, and the Association of Zoos and Aquariums instituted Species Survival Plans to help.

Several viper species are listed in the IUCN Redlist of Threatened Species, and many are also listed with CITES to limit international trade in threatened and endangered species. Conservation groups worldwide help protect these dangerous but vital reptiles, and as knowledge increases in localities, so do the protection and people’s willingness to learn to live alongside them.

Reproduction, Babies, and Lifespan

Most vipers give birth to live young.

©Alexey Stiop/Shutterstock.com

Mating season for vipers varies greatly because those in the northern latitudes need more time to warm up, and the females may only breed once every 3-4 years. Vipers in warmer climates (like Russel’s viper) may breed all year long. One thing that these snakes do have in common (for the purpose of this article, we won’t include the Causus genus) is that they give birth to their young. Like pit vipers, they don’t lay eggs. Instead, the babies develop inside the mother until they’re ready to be born. Mothers in some species stay with their young for a few days or weeks, often until the neonates have had their first shed. However, others head right out on their own.

Similar Animals

Vipers are highly venomous and are not native to the Americas. However, all is not lost! North, Central, and South America all have venomous snakes – they’re called pit vipers. Many of them have similar features to the Old World vipers – the stocky body, big angular heads, and retractable fangs.

- Eastern diamondback rattlesnake is known for the diamond-shaped markings along their back. It’s also one of the largest rattlesnakes in the world.

- Fortunately, copperheads are relatively docile. However, they’re still venomous pit vipers and are native to the Southeast United States.

- Midget faded rattlesnakes are appropriately named. They’re very small, and as they mature, their color patterns fade.

- Canebrake or timber rattlesnake is the one you may have seen on the “Don’t Tread on Me” flag, known more properly as the Gadsden flag.

- Bushmasters are highly venomous and yet very shy. These snakes are native to South America.

Viper FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

What's the difference between vipers and other venomous snakes?

The biggest difference between vipers and other venomous snakes is their big, hypodermic-needle-type fangs. They’re attached to moveable bones in the upper jaw, called the maxillaries, and rotate into position and back into the jaw when they’re not needed. Cobras, kraits, and mambas have fixed fangs that do not move.

Where do vipers live?

Vipers (not to be confused with pit vipers) live in most parts of Europe, Asia, and Africa. They’re a widespread and diverse group of snakes.

What do vipers eat?

Vipers eat a wide variety of animals. Depending upon the species, they may eat arthropods, birds, mice, rats, birds, etc.

How do vipers hunt?

Most species are preeminent ambush predators. Their camouflage and ability to sit still for days make them excellent at this. However, some species actively forage for their food too.

Are vipers venomous?

Yes!! Some more so than others, and some species are more likely to bite than others. However, all vipers are venomous.

Are vipers aggressive?

Not most of them. Most species are rather timid and would rather hide. However, a few are known to either be aggressive or easily upset and quick to bite.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- Lynn, W. Gardner. “On the Supranasal Sac of the Viperinae.” Copeia 1935, no. 1 (1935): 9–12. https://doi.org/10.2307/1436628., Available here: https://doi.org/10.2307/1436628

- Goris, Richard C. “Infrared Organs of Snakes: An Integral Part of Vision.” Journal of Herpetology 45, no. 1 (2011): 2–14. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41415237., Available here: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41415237

- Di Nicola, Matteo R et al. “Vipers of Major clinical relevance in Europe: Taxonomy, venom composition, toxicology and clinical management of human bites.” Toxicology vol. 453 (2021): 152724. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2021.152724, Available here: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33610611/

- True Vipers, Viperinae | inaturalist.org, Available here: https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/797529-Viperinae

- Animals, Poisonous and Venomous |Science Direct , Available here: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/viperinae