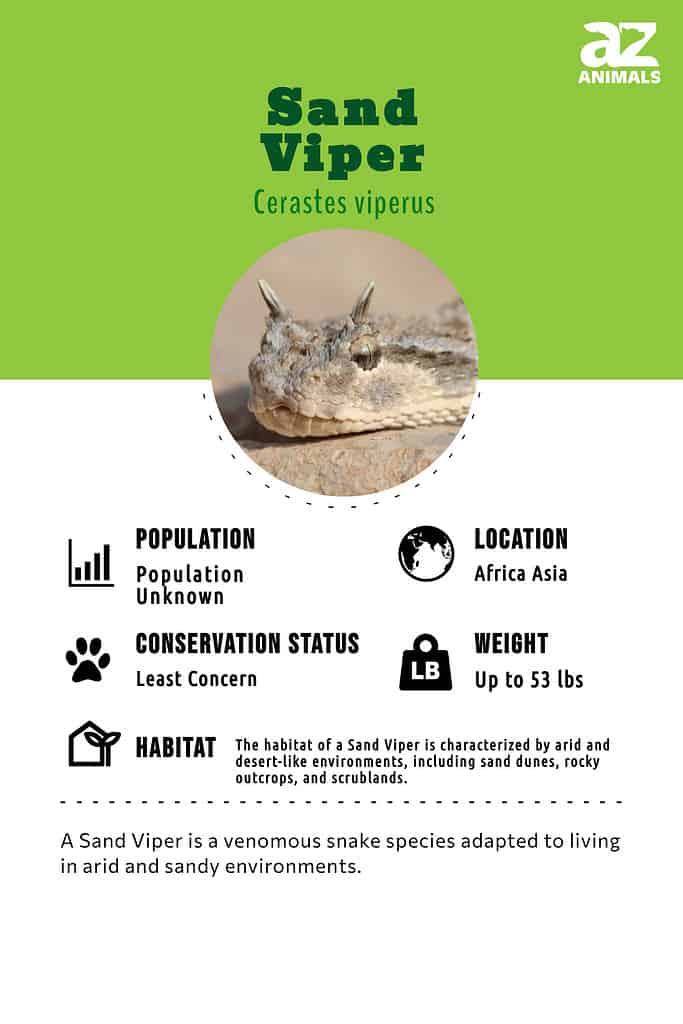

Sand Viper

Cerastes viperus

Sand vipers are nuisance snakes in some areas.

Advertisement

Sand Viper Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Reptilia

- Order

- Squamata

- Family

- Viperidae

- Genus

- Cerastes

- Scientific Name

- Cerastes viperus

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Sand Viper Conservation Status

Sand Viper Facts

- Prey

- lizards, geckos, small mammals

- Group Behavior

- Solitary

- Fun Fact

- Sand vipers are nuisance snakes in some areas.

- Other Name(s)

- Saharan Sand Viper, Common Sand Viper

View all of the Sand Viper images!

“Sand vipers burrow into the sand and strike directly from their hiding place.”

Found throughout the deserts of North Africa, the sand viper is a versatile and deadly hunter that can shift between active and ambush hunting depending on the needs of its environment. As a close relative of the geographically proximate horned viper, the sand viper shares the general appearance, tactics, and deadly venom of its more dramatically designed cousin.

Though it can only be found in desert environments, the versatility and lethality of this species have allowed its spread from North Africa to Sudan to Israel. In keeping with that wide distribution, the sand viper snake is often known as the common sand viper or the Sahara viper.

3 Incredible Sand Viper Facts!

The horns over the eyes are the most distinctive feature of the horned viper.

©iStock.com/bogdanhoria

- Sand vipers actually give birth to live young rather than laying eggs. They can give birth to as many as eight young at once, and they’re born active and venomous.

- Females of the species can also be defined at a glance by the fact that they have black tails and are somewhat larger than males.

- While they primarily operate as ambush predators, sand vipers are known to employ active hunting methods in the time leading up to periods of brumation — a state similar to hibernation but for reptiles. This allows them to store extra nutrients and fat for the winter.

Evolution and Origins

The earliest known fossils of vipers date back to the lower Miocene era, although molecular studies suggest that the Viperidae family has a much older origin that dates back to the early Eocene period.

Vipers originated in the Old World, with pitvipers later colonizing the New World and quickly spreading throughout North, Central, and South America.

The horned desert viper exhibits distinctive anatomical, physiological, or behavioral adaptations. The horns on the snake’s head may serve as a protective mechanism for the eyes, or they may contribute to the camouflage of its environment.

Additionally, this species can move rapidly through the sand by performing sideways movements of its body, allowing it to burrow quickly while keeping only its head and eyes visible.

Different Types

There are three different types of sand vipers, and they are:

- The nose-horned viper, also known as Vipera ammodytes, is a venomous snake species found in Europe, the Balkans, and parts of the Middle East.

- The Avicenna viper, or Cerastes vipera, is another venomous snake species found in the deserts of North Africa and the Sinai Peninsula.

- Hog-nosed snakes, also called Heterodon, are a genus of harmless colubrid species found in North America.

Where To Find Sand Vipers

The Sahara viper is accurately named in that it’s found throughout North Africa‘s Sahara Desert, but that’s not the only location where these reptiles can be found. The habitats for these reptiles continue to stretch east over the Suez Canal and then further still into the states of the Arabian Peninsula.

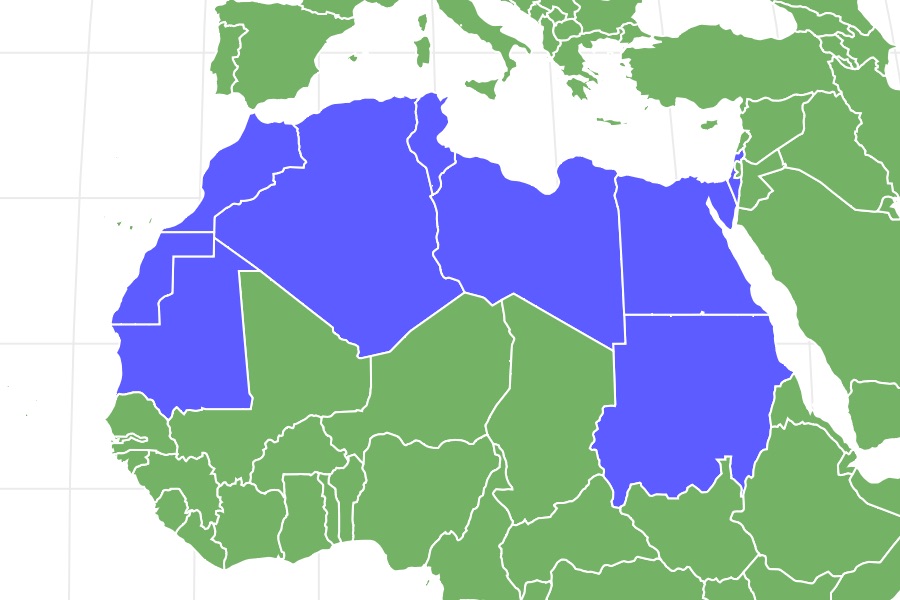

All told the facts to show that the sand viper snake has developed an impressively broad geographic range for its habitats. This habitat range includes all of North Africa’s northernmost states: Mauritania, Western Sahara, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, and Sudan. To the east, it extends into small portions of Israel.

But the Sahara viper’s habitat notably extends only as far as the desert. Everything from their colors to their physiologies to their hunting habits is adapted specifically to desert habitats. But that also means that these snakes would have a hard time surviving anywhere outside of the arid desert sands. The facts show why this is so common for snakes.

As cold-blooded reptiles, they thrive in hot environments, and they’re capable of surviving with only periodic feedings and little in the way of hydration. The sand is particularly useful to the Sahara viper — as these snakes can hide beneath the surface of the sand and go unnoticed thanks to their colors, and their sidewinding style of locomotion allows them to effectively navigate the slippery desert sand.

Scientific name

The scientific name of the sand viper is Cerastes viperus, and it does a pretty good job of telling the average herpetologist the basics about the species. Cerastes is a reference to a mythical serpent in classical Greece that’s lethally fast and incredibly flexible thanks to its lack of a spine.

And while that’s certainly in keeping with the ambush hunting style and the sidewinding movement of this species, Cerastus is also a reference to the snake’s genus. All four members of this genus are classified as vipers, and most of them are indistinguishable from the average observer and lacking in detailed scientific analysis thanks to their similarities.

The most popular and most distinct of the Sahara viper’s genus-mates is the horned viper. This snake looks just like the sand viper apart from the horned ridge over its head, and they have very similar habits apart from the fact that sand vipers give birth to live young.

Population and Conservation Status

The relatively wide geographic distribution of the common sand viper and the ability of the Cerastes genus to sustain four different species throughout that range is a good sign for the continued conservation of the sand viper. This snake is currently listed as least concern by the IUCN, which means its population is stable and over 10,000. Barring dramatic climate or habitat shifts, this snake should be safe for the foreseeable future.

Appearance and Description

©reptiles4all/Shutterstock.com

As creatures honed through generations to excel as ambush predators, the colors and size of the common sand viper are designed to blend into the deserts where they hunt for prey — but identification is made even more challenging by the three species of similarly related snakes that also call North Africa and the Sinai Peninsula home.

The common sand viper can be distinguished from the closely related horned viper thanks to its absence of protrusions over its head, but identification would be difficult otherwise. Both are thin snakes that can reach a size of around a foot and a half, and both exhibit a tan base with slightly darker markings that help them more readily conceal themselves from prey.

Venom: How Dangerous Are They?

The sand viper’s venomous bite has a critical role to play in its efficacy as a predator. And as some of the smaller snakes in the locations they inhabit, venom allows them to improve their lifespan by minimizing the risk of attack by their prey animals.

A sand viper will merely use their bite to inject prey with venom and let them loose as soon as possible. The venom then does all the work, so the viper can wait to consume its prey until it’s already dead or at least incapacitated.

Though this poison is capable enough to take down prey like mice, birds, and amphibians, the bite of a common sand viper isn’t especially dangerous to humans. It’s unlikely to die from a sand viper bite thanks to the comparative mildness of the venom.

Behavior and Humans

Sand vipers are elusive wild animals — and while they’re a relatively common sight throughout locations spanning Africa and the Middle East, their direct interaction with humans is generally sparse. Sand vipers aren’t kept as pets, though they are sometimes considered a nuisance in the regions where they’re found. Though nonlethal, the venom they can inject is capable of causing cell damage and can be very painful.

Sand vipers don’t consider humans to be prey, and they’re just as likely to dry bite a human as they are to inject them with venom. In either case, they’d generally rather avoid humans than confront them — but a Saharan sand viper isn’t above striking out when it feels threatened.

View all 293 animals that start with SSand Viper FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

What does a sand viper look like?

Stocky and roughly 18 inches long, the Saharan sand viper is light tan with tick markings colored a darker shade of brown. As a result, these spiders can be very hard to identify when they’re buried in the sand waiting for prey.

Where does the sand viper live?

The Saharan sand viper thrives in the desert, and they’ve managed to develop a habitat that spans the entirety of North Africa and much of the Sinai Peninsula. But as soon as you begin to leave the desert, Saharan sand vipers cease to have a presence.

Is a sand viper poisonous?

Sand vipers employ an anticoagulant venom that can interfere with the bleeding process as well as force swelling and minor necrosis. This quickly anticipates the prey sand vipers hunt, though it’s rare that a Saharan viper’s venom actually cuts a human’s lifespan shorter.

How fast is a sand viper?

Sand vipers move by sidewinding — a unique technique that minimizes their exposure to the ground to prevent overheating and avoid slipping on loose sand. While the land speed of the sand viper hasn’t been recorded, the American sidewinder employs a similar locomotion method and can reach speeds approaching 20 miles per hour.

Where do sand viper snakes come from?

Sand viper snakes are one of four species under the genus Cerastes. Along with their brethren, they can be found in desert environments throughout North Africa and the Middle East.

How do sand vipers hunt?

Sand vipers are ambush predators who will hide beneath the sand and then wait for prey to come near. Once within reach, they’ll strike out with their venomous bite, retreat, and wait for their prey to die from the toxin.

Are sand vipers aggressive?

While sand vipers will normally avoid humans, they’re aggressive predators with a mean bite. Humans aren’t part of their diet but should avoid contact whenever possible.

What do sand vipers eat?

Sand vipers are opportunistic predators with venom that allows them to target prey that might otherwise be too large. Their diet includes a variety of rodents, geckos, and reptiles. The Anderson’s short-fingered gecko is a particularly common prey species for sand vipers.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- Animal Diversity Web, Available here: https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Cerastes_gasperetti/classification/#Cerastes_gasperetti

- eol, Available here: https://eol.org/pages/2817781

- Fauna Facts, Available here: https://faunafacts.com/snakes/can-you-outrun-a-snake/

- kidadl, Available here: https://kidadl.com/animal-facts/sand-viper-facts