The largest freshwater turtle known to have ever lived!

Advertisement

Stupendemys Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Reptilia

- Order

- Testudines

- Family

- Podocnemididae

- Genus

- Stupendemys

- Scientific Name

- Stupendemys geographica

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Stupendemys Conservation Status

Stupendemys Facts

- Prey

- Fish, mollusks, snakes, other reptiles

- Main Prey

- Fish

- Fun Fact

- The largest freshwater turtle known to have ever lived!

- Estimated Population Size

- Extinct

- Biggest Threat

- Giant crocodilians, climate change

- Most Distinctive Feature

- Massive size

- Distinctive Feature

- Bony horns on carapace of males

- Other Name(s)

- Stupendemys geographicus, Stupendemys souzai, Stupendemys

- Habitat

- Wetlands

- Predators

- Giant crocodilians

- Diet

- Omnivore

- Common Name

- Stupendemys

- Special Features

- Massive size, huge skull, horns on carapace of males

- Number Of Species

- 2

- Location

- South America - Venezuela, Colombia, Peru and Brazil

View all of the Stupendemys images!

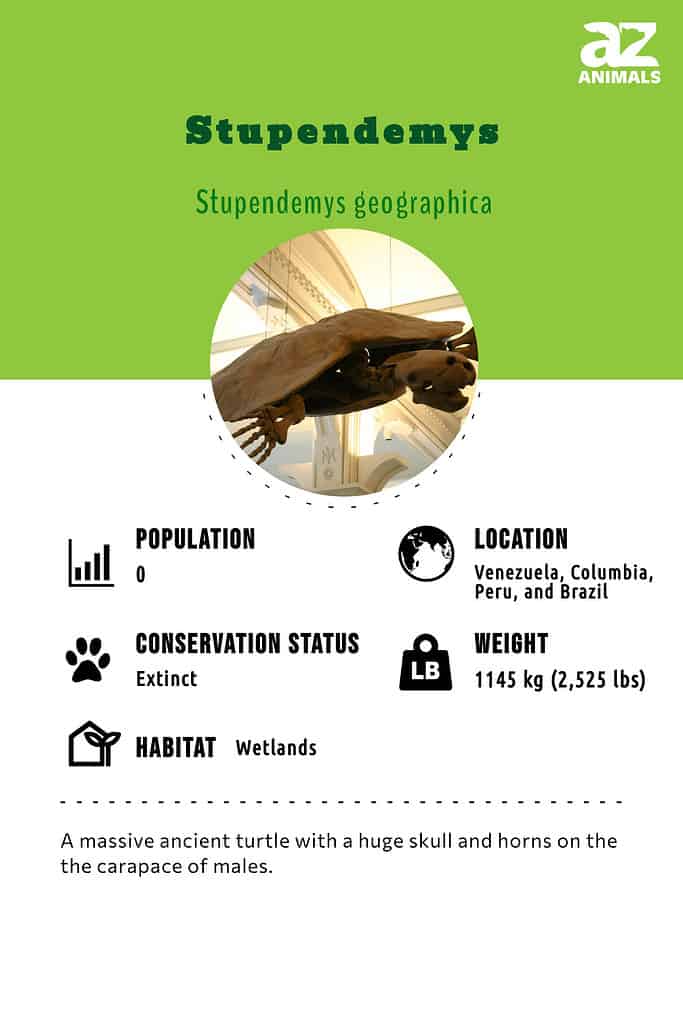

The astoundingly large Stupendemys geographica (formerly known as Stupendemys geographicus) is an extinct freshwater turtle. It was found in South America during the Miocene era and is thought to be the largest freshwater turtle species ever to have lived. Only one known turtle species was larger, but it lived in the sea. The shell of the Stupendemys was roughly the size of a car. First discovered in 1972, scientists named this stupendous creature for its enormous size.

©

Stupendous Stupendemys Facts

- Stupendemys geographica was one of many giant animal species that lived in South America millions of years ago.

- The Stupendemys turtle lived in a huge freshwater wetland that covered much of the northern part of South America, including parts of Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, and Brazil.

- Factors including a huge habitat, abundant food, and pressure from giant predators all had a role in the enormous growth of this species.

- The natural predators of the Stupendemys turtle were crocodilians that grew over 33 feet long – the length of a standard school bus.

- The largest known Stupendemys had a carapace roughly 11 feet long.

- Based on recently found fossils, researchers believe this turtle may have lived as long as 110 years before reaching its full size.

- The name, Stupendemys, means stupendous turtle.

Species and Scientific Name

There are at least two genera of giant, side-necked turtles: Stupendemys and Caninemys. Although they were roughly the same size, they are quite different otherwise. Caninemys fossils show evidence of a different feeding strategy – with Caninemys deploying a vacuum feeding method that was supported by tooth-like structures in the creature’s maxilla. Stupendemys are more similar to modern turtles and are thought to have eaten fish and seeds that they distributed throughout the wetlands – perpetuating the flora in the ancient turtle’s habitat.

There have been two species of Stupendemys found thus far: Stupendemys geographica and Stupendemys souzai. Fossil evidence of S. souzai has been found in the same regions as Caninemys. The name Stupendemys is a combination of “stupendous” and the Latin word “emys” for freshwater turtle. The species’ name honors the National Geographic Society.

Evolution

was the earliest known ancestor of turtles and existed around 260 million years ago.

©Smokeybjb / CC BY-SA 3.0 – License

The earliest known ancestor of modern turtles was Eunotosaurus, a reptile that existed during the Permian epoch, around 260 million years ago. Eunotosaurus didn’t have a shell but did have the framing for one with wide ribs that shielded the animal’s underside. Recent studies reveal that those wide ribs aided the animal in digging and burrowing by anchoring it to the ground. Eunotosaurus had evolved to be an efficient excavator. The animal was once thought to be a swimmer but the big claws and thick bones would have helped it to withstand compressive forces while burrowing. The powerful, back-facing front limbs and weaker back limbs indicated a master borrower.

Eunotosaurus fossils have been found in what is now, South Africa, and this turtle relative lived during a period when the land was dry and arid. The animal may have evolved its burrowing ability to escape droughts. Boney rings around Eunotosaurus’s eyes indicate that it may have spent a lot of time underground.

Pappochelys and Odontochelys also seemed to be equipped with digging abilities. It is believed that after the digging adaptations were made – many turtles became aquatic. Over time, complete shells formed from the wide ribcage, perhaps to protect the slow-moving turtles hampered by broad ribs from predators. Digging platforms evolved into suits of armor.

Description & Size

is thought to be the largest freshwater turtle that ever lived.

©Ryan Somma/Flickr – License

Stupendemys geographica cannot be described without referencing its sheer size. It is, after all, thought to be the largest freshwater turtle that ever lived.

Scientists who have studied the creature most frequently reference its straight carapace length when discussing its size. That is, in essence, the straight length from the front edge of the turtle’s shell, where its neck emerges, to the back edge, where its tail protrudes. The measurement is not taken up and over the curved edge of the carapace. Also, it does not include the length of the turtle’s head, neck, tail, or feet.

The straight carapace length of the Stupendemys ranges from around nearly 11 feet. That’s roughly the length of a subcompact car, and that’s just the shell.

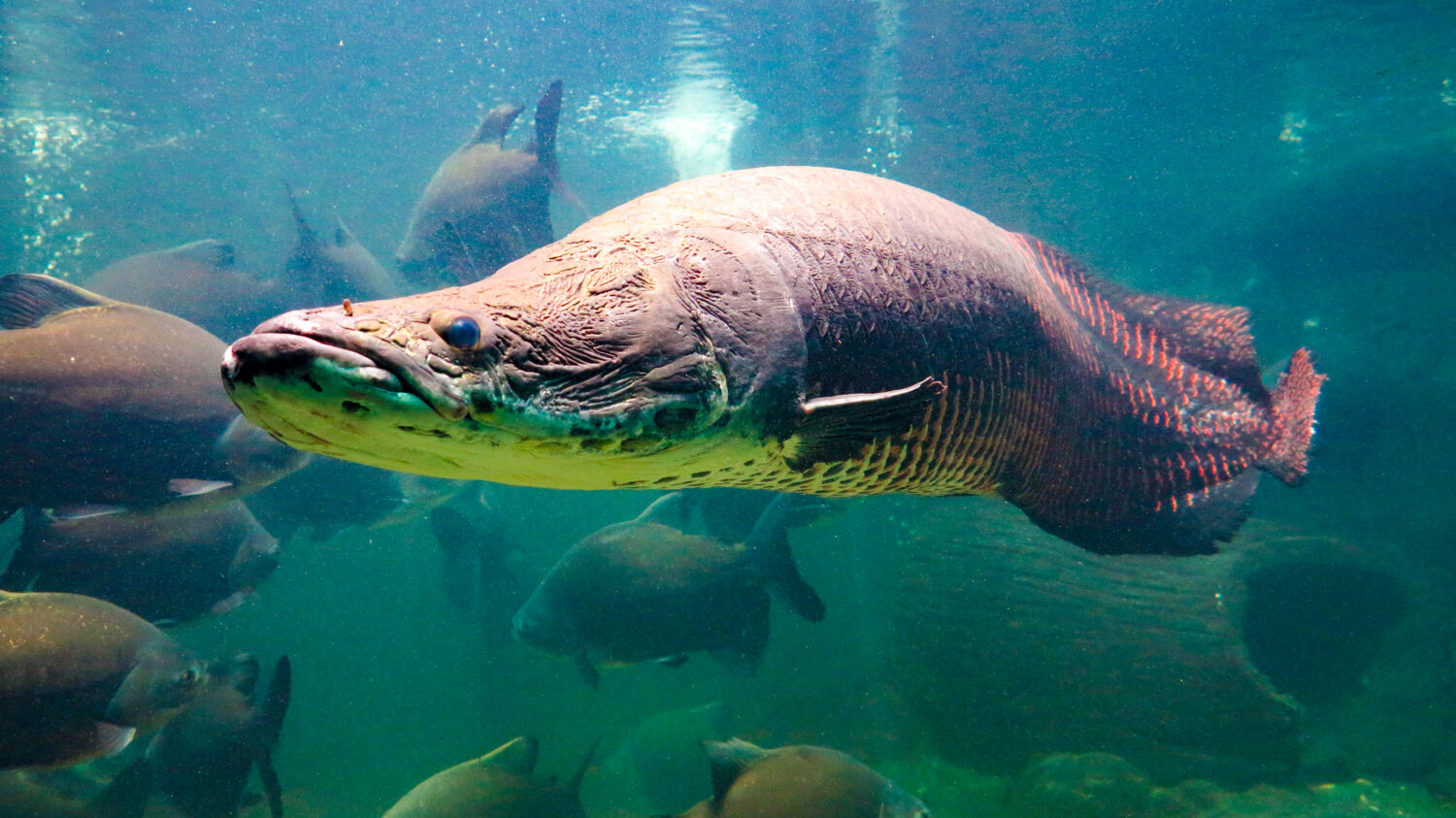

The big-headed Amazon river turtle is the closest modern relative of

S. geographica.

Image: guentermanaus, Shutterstock

©guentermanaus/Shutterstock.com

Using estimates based on the straight carapace length and other factors, researchers estimated the mass of the largest known S. geographica specimen. Estimates vary based on the method used, but researchers say the turtle probably had a mass of more than 2,500 pounds. The only known turtle that was larger was the Archelon sea turtle.

A team of scientists in 2007 did extensive research on the bone structure of the Stupendemys, comparing it to other living turtles and tortoises. They found that S. geographica was sexually dimorphic. Males had horn-like protrusions on the front of the carapace, which they possibly used for fighting.

They also found that the carapace was more flattened than rounded and was relatively lightweight. This was due to the cancellous or spongy structure of the bone itself. This discovery explained why the turtle was particularly well suited for swimming in freshwater, where the lack of salt reduces buoyancy.

Diet – What Did Stupendemys Eat?

probably preyed on ancestors of the

Arapaima

– fossils of the fish have been found from the Miocene era.

Image: SergioRocha, Shutterstock

©SergioRocha/Shutterstock.com

Scientists today do not have the benefit of analyzing stomach contents or observing the habits of an extinct creature in the wild. They must rely on other methods to determine what the Stupendemys ate. They do have a number of clues based on the size of the S. geographica skull and the formation of its massive jaws and teeth.

Based on the huge skull and strong jaw of this turtle, scientists assume that the species ate a wide variety of fish, mollusks, snakes, and other reptiles. Researchers also believe that the strong jaw of the Stupendemys allowed it to eat all manner of seeds and fruits.

Based on the dietary habits of its nearest living relative, the big-headed Amazon river turtle, scientists believe that S. geographica may have been responsible for dispersing the seeds of various plants throughout its South American wetland home.

Habitat – When and Where Stupendemys Lived

lived in a giant wetland where South America is today.

©iStock.com/Petmal

Stupendemys geographica lived in a giant wetland that covered much of modern South America from around 13 million years ago to about 5 million years ago, during the Miocene era and into the Pliocene era. The first S. geographica specimen, described in 1972, was unearthed in Venezuela. Researchers discovered subsequent specimens in Venezuela, and later in Colombia, Peru, and Brazil.

Wetlands covered much of the continent before the waters receded to the Amazon and Orinoco river basins. These waterways were expansive and interconnected. Researchers believe that such habitat was able to support the growth not only of huge individuals but of entire species as a whole. Many species that lived in the area at the time were enormous, including the Stupendemys. Fossils of prehistoric giants have been found over wide-ranging regions in South America where the wetlands once were.

Threats and Predators

was one of the giant crocodilians that preyed on

Stupendemys geographica.

Image: di Lissandro, Shutterstock

©di Lissandro/Shutterstock.com

One of the factors thought to have affected the size of the Stupendemys is its interaction with predators. S. geographica shared a habitat with giant crocodilians such as the Gryposuchus and the Purussaurus, These monsters could grow to be more than 10 meters in length. That’s about the size of a standard 72-passenger school bus!

Fossil evidence demonstrates that these turtles bore the brunt of vicious attacks from those massive crocodilians. Some specimens had bite marks from predatory encounters. Another specimen found recently had a giant embedded tooth in the underside of its carapace. S. geographica had to evolve to great size as a means of survival for the species.

Discoveries and Fossils – Where Was Stupendemys Found?

Fossils of

Stupendemys geographicalwere found in the Tatacoa desert of Colombia.

Image: Explorelixir, Shutterstock

©Explorelixir/Shutterstock.com

A group of researchers, led by Roger Conant Wood, were the first to discover Stupendemys fossils in 1972. They were astounded by the size of the species, which was larger than any freshwater turtles ever known. Wood published an extensive account of the group’s findings in the April 1976 edition of Brevoria, the journal of the Harvard University Museum of Comparative Zoology.

Scientists later found additional fossils throughout the northern part of South America. They ranged from Venezuela to Colombia, Brazil, and Peru. Brazilian scientists described a second species, Stupendemys souzai in 2006. This entire region was once covered by an extensive and interconnected lake and wetland system known as the Pebas System. The most recent specimens were found in 2020. They came from what is now the Tatacoa desert of Colombia and the Urumaco region of Venezuela.

Extinction – When Did Stupendemys Die Out?

Stupendemys geographica lived through much of the Miocene era into the Pliocene era. It became extinct as recently as about 5 million years ago. Researchers believe that climate change and the draining of the wetland system that covered northern South America led to the extinction of the species.

Related Animals…

- Archelon – The largest turtle ever recorded.

- Leatherback Sea Turtle – This is the largest living sea turtle.

- Aldabra Giant Tortoise – This is one of the largest living tortoise species.

- Snapping Turtle – This is a predatory turtle common in North and South America.

.

View all 293 animals that start with SStupendemys FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

When was the Stupendemys alive?

S. geographica was alive during the Miocene era through the Pliocene era, from about 13 million to about 5 million years ago.

How big was the Stupendemys?

This giant turtle was up to 1145 kg, or 2500 pounds. The largest specimen found to date had a carapace that measured 3.3 meters in length, or close to 11 feet.

Why was Stupendemys so big?

Scientists believe that one of the main reasons was that it evolved to greater and greater size in order to survive predation by giant crocodilian species. Also, the abundant food and habitat probably supported the growth of the species.

Where was the Stupendemys found?

S. geographica was found in the northern part of South America, in an expansive wetland that covered much of what is now Venezuela, Colombia, Peru and part of Brazil.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- Scheyer, T.M. and Sanchez-Villagra, M.R., Available here: https://www.app.pan.pl/archive/published/app52/app52-137.pdf

- Cadena, et al., Available here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7015691/

- Museum of Comparative Zoology, Available here: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/6590428#page/533/mode/1up

- Bocquentin, J. and Melo, J., Available here: https://www.sbpbrasil.org/revista/edicoes/9_2/RBP9-2-Jean.pdf