Kokanee Salmon

Oncorhynchus nerka

They change color in preparation for spawning!

Advertisement

Kokanee Salmon Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Actinopterygii

- Order

- Salmoniformes

- Family

- Salmonidae

- Genus

- Oncorhynchus

- Scientific Name

- Oncorhynchus nerka

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Kokanee Salmon Conservation Status

Kokanee Salmon Facts

- Prey

- Zooplankton, freshwater shrimp, aquatic insects

- Main Prey

- Zooplankton

- Name Of Young

- Fry

- Group Behavior

- School

- Fun Fact

- They change color in preparation for spawning!

- Biggest Threat

- Chinook salmon

- Most Distinctive Feature

- Reddish flesh

- Other Name(s)

- Kokanee trout, silver trout, Kennerly’s trout, Kennerly’s salmon, little redfish, kikanning, Walla

- Incubation Period

- 110 days

- Average Spawn Size

- 1,000 eggs

- Predators

- Chinook salmon, rainbow trout, char, sturgeon, burbot, bears, wolves, otters, bald eagles, humans

- Diet

- Omnivore

- Lifestyle

- Diurnal

- Common Name

- Kokanee salmon

- Origin

- North America

- Number Of Species

- 1

- Slogan

- A non-anadromous type of sockeye salmon

Kokanee Salmon Physical Characteristics

- Color

- Red

- Blue

- White

- Green

- Silver

- Olive

- Skin Type

- Scales

- Top Speed

- 1.8 mph

- Age of Sexual Maturity

- 4 years

- Venomous

- No

- Aggression

- Medium

View all of the Kokanee Salmon images!

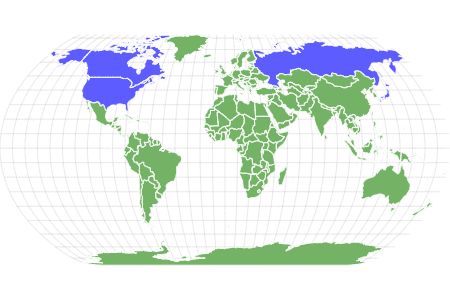

The kokanee salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) is a non-anadromous type of sockeye salmon. Alternate names for this fish include kokanee trout, silver trout, Kennerly’s trout, Kennerly’s salmon, little redfish, kikanning, and Walla. Like other Pacific salmon, it only spawns once and then dies, limiting its lifespan to four or five years. It inhabits land-locked freshwater lakes in the United States, Canada, Russia, and Japan.

4 Kokanee Salmon Facts

- They die after spawning: These fish are semelparous, which means they only spawn once before they die. Since they only spawn in their four or fifth year, very few members of this species live past that mark.

- They change color: During spawning season, both males and females change color from a bluish-silver to bright or dark red. Males are more vibrant than females.

- They’re a subspecies of sockeye: These fish aren’t a separate species; rather, they’re a type of nonmigratory sockeye salmon.

- They lay eggs in a trench: Females dig a trench or “redd” with their tails, then lay eggs inside. Males release milt to fertilize the eggs, which may number well over 1,000.

Kokanee Salmon Classification and Scientific Name

The scientific name for kokanee salmon is Oncorhynchus nerka. The name is a mixture of Greek and Russian. Oncorhynchus derives from the Greek terms for “nail” and “snout” while nerka is the Russian word for anadromous sockeye salmon. Kokanee salmon are a type of sockeye that are non-anadromous, or land-locked. Unlike this species, most sockeye are migratory, moving upriver from the ocean to spawn. Kokanee comes from the Sinixt word kekeni, an Indigenous term for the land-locked form of sockeye.

The species belongs to the class Actinopterygii (ray-finned fishes) within the superclass Osteichthyes (bony fishes). Scientists further place it in the order Salmoniformes and the family Salmonidae, which contains 11 genera and 66 species of salmon. Sockeye, including kokanee, belong to the genus Oncorhynchus (Pacific salmon and trout).

Kokanee salmon (

Oncorhynchus nerka) is a type of sockeye that are non-anadromous, or land-locked.

©U.S. Forest Service- Pacific Northwest Region / Flickr

Kokanee Salmon Appearance

Prior to spawning, kokanee salmon have steel blue to bluish-green heads and backs, silver sides, and silvery-white bellies. Unlike most other salmon and trout, they do not have dark spots on their backs, though they may have speckles on their dorsal fins. During spawning, males develop a hump and a hooked jaw with teeth (a “kype”). They also turn bright red with dark green heads and black snouts and jaws. Females undergo a similar change, though their colors are duller. The color change is a result of a diet rich in carotenoids, which are pigments responsible for bright red, orange, and yellow coloration in animals and plants. The bright red attracts potential mates, but it also makes these fish more vulnerable to predators.

These land-locked fish are typically smaller than anadromous sockeye. This is likely due to a less robust food supply in lakes and rivers as opposed to marine environments. While sockeye can grow up to 33 inches long and weigh as much as 17 pounds, kokanee salmon usually measure no more than 12-15 inches. They can weigh between three to five pounds, though most individuals don’t exceed one pound. However, the largest kokanee on record according to the International Game Fish Association (IGFA) measured 27 inches in length and weighed an impressive 9.67 pounds.

This species has fine scales that arrange themselves in rings, which (much like the rings of a tree) can help determine an individual’s age. It also has six types of fins with eight individual fins in total: a dorsal fin, an adipose fin, a caudal fin, an anal fin, two pelvic fins, and two pectoral fins.

Kokanee salmon (

Oncorhynchus nerka) turn bright red during spawning to attract mates.

©topseller/Shutterstock.com

Kokanee Salmon Distribution, Population, and Habitat

Kokanee salmon inhabit land-locked areas of the United States, Canada, Russia, and Japan. Within the United States, they occur in a number of states including Alaska, Washington, Oregon, California, Montana, Idaho, New York, Wyoming, Nevada, Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, New England, North Carolina, and Utah. In Canada, they inhabit British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and the Yukon Territory.

These fish spend their whole lives in cool lakes, typically swimming at depths of 15-90 feet, though some go deeper than this. At spawning time, they move closer to the shore or upstream into tributaries.

The IUCN has not assessed the conservation status of kokanee salmon as of 2022. As of 2010, it lists sockeye salmon as Least Concern due to its stable populations. However, NOAA Fisheries lists sockeye populations in Lake Ozette (Washington) and Snake River (Idaho) as protected under the Endangered Species Act. The WWF warns of potential threats to other Pacific salmon species including climate change, poaching, habitat destruction, river blockages, and overharvesting. You can find a list of endangered species here.

Kokanee salmon are typically smaller than anadromous sockeye due to a less robust food supply in lakes and rivers.

©gwb/Shutterstock.com

Kokanee Salmon Evolution and History

The ancient ancestors of kokanee salmon lived as far back as 65-95 million years ago in the Cretaceous Period. During this time, they underwent a significant autotetraploid event in which they developed twice the number of chromosome arms and DNA content. Scientists speculate that this resulted in greater diversity and faster evolution.

By the early Miocene Epoch, approximately 15-20 million years ago, two genera within Salmonidae split from each other. The first genus, Salmo, comprises Atlantic salmon; the other, Oncorhynchus, contains Pacific salmon. Oncorhynchus speciated throughout the Miocene, producing all extant species by six million years ago. Although fossils of Pacific salmon from the ensuing Pleistocene are rare, scientists speculate that northwestern North America’s active geologic history inspired greater diversity among Oncorhynchus than Salmo.

It is possible that kokanee salmon came from lake-type sockeye rather than sea-type sockeye. The lake-type may have become land-locked at some point and evolved into its current non-anadromous form. Taxonomists currently debate whether or not kokanee and sockeye salmon belong to two different species. Though they often inhabit the same habitats during spawning season, the two types do not automatically mate with each other.

Interestingly, one study in Skaha Lake, British Columbia introduced a sockeye population to a kokanee population and observed the hybrid spawn. It discovered that 92% of hybrid individuals were non-anadromous with 76% being the offspring of resident non-anadromous females. Some sockeye offspring have been known to become non-anadromous while some kokanee offspring have become anadromous.

Black Kokanee Salmon

A unique subtype of kokanee, black kokanee, exists in Lake Saiko in Japan and the Anderson and Seton lakes in British Columbia. Some scientists consider the Japanese type to be its own species, Oncorhynchus kawamurae. These isolated populations on either side of the Pacific exhibit black nuptial coloration and spawn much deeper than most sockeye salmon, anywhere between 65-230 feet below the surface.

The lack of shared mtDNA haplotypes or a monophyletic grouping suggests that the Japanese populations likely split from the Anderson-Seton populations during two different evolutionary episodes. This may correspond to the multiple proposed postglacial splits of regular kokanee from sockeye.

Kokanee Salmon Predators and Prey

Kokanee salmon are omnivores, though they prefer animal matter to plant matter. Because of their small size, they are restricted to diminutive prey and are themselves easy targets for a number of predators.

What Do Kokanee Salmon Eat?

Kokanee salmon eat zooplankton, aquatic insects, freshwater shrimp, and small plants. Since zooplankton are so tiny, these fish use comb-like gill rakers on their gills to separate miniscule organisms from the water.

What Eats Kokanee Salmon?

Chinook salmon are the primary predators of kokanee salmon along with other large fish like rainbow trout, char, sturgeon, and burbot. They are also the targets of bears, wolves, otters, osprey and bald eagles, not to mention humans. The risk increases dramatically during spawning season when both males and females turn a conspicuous red.

Large birds such as the osprey feed on kokanee salmon.

©Gregory Johnston/Shutterstock.com

Kokanee Salmon Reproduction and Lifespan

Unlike sockeye, kokanee salmon do not migrate from the rivers of their birth to the ocean. Instead, they move to nearby lakes, where they spend four to five years growing and maturing. After this, they reach sexual maturity and are ready to spawn either in the lake shallows or upstream in tributaries. Like all Pacific salmon, they are semelparous, dying soon after spawning. Because of their mating habits, these fish live only four to five years.

Typically in their fourth year, males and females make their way to the site of their birth during a period of time called a “run.” Runs occur between August and December depending on the location. The female digs a trench, or a “redd.” Other, subordinate males may be in attendance, though the dominant male will fight them off using his kype and hump. The female may also be aggressive toward them as well as other females.

Once ready, the female and dominant male descend together into the redd. They gape and vibrate until they release eggs and milt (sperm). One female typically lays approximately 1,000 eggs, though she may lay more or less depending on the availability of food sources. The other males may also release their milt on her other side.

The female covers the fertilized eggs as she digs a new redd just upstream in preparation to spawn again. Both males and females may mate with multiple partners. The eggs incubate for approximately 110 days, usually hatching in February or March. Newly-hatched alevins depend on attached egg-yolk sacs for nutrition for the first two to three weeks of life. Once they develop into fry and then juveniles, they move downstream to a nearby lake or into deeper waters to feed and grow.

Kokanee salmon spawn either in lake shallows or upstream in tributaries and like all Pacific salmon, they die soon after spawning.

©IrinaK/Shutterstock.com

Kokanee Salmon in Cooking and Fishing

Kokanee salmon are popular recreational or sport fish, though other sockeye salmon are important to commercial fisheries. NOAA estimates the 2021 worldwide commercial catch for sockeye salmon at 272 million pounds with a total value of $459 million. The vast majority of sockeye comes from Alaska, though fisheries net smaller numbers off the West Coast, mainly around Washington and Oregon. Though they are great for canning, these fish are also good fresh or frozen. For this species, fisheries typically use gillnet purse seines or reef nets.

Though kokanee salmon are small, they are aggressive and fight hard to free themselves, making them valuable to recreational and sport anglers. These fish travel in schools, making it possible to catch multiple fish in one session. They are active during the day but are likeliest to bite at dawn and dusk when the light is low. The best types of bait are pink maggots, dye-cured shrimp, or canned corn, though anglers should be careful not to overload their hooks. One or two pieces of bait per hook should be sufficient.

Kokanee salmon flesh is soft, rich, and vibrantly red with a pleasant, relatively mild taste. Acceptable ways to cook kokanee salmon include grilling, roasting, frying, smoking, and baking. Check out this comprehensive guide to smoked kokanee or explore a number of methods for preparing this delectable fish. This recipe for herbed kokanee with roasted garlic and lemon butter is a great way to get started.

This fish yields relatively lean meat much like that of sockeye flesh. Per 155 grams, it contains 261 calories, 39 grams of protein, and 10 grams of fat.

Related Animals

View all 77 animals that start with KKokanee Salmon FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Are kokanee salmon and sockeye salmon the same thing?

Kokanee salmon are non-anadromous (landlocked) sockeye salmon, which means they belong to the same species, Oncorhynchus nerka. Instead of migrating to the ocean to feed, kokanee salmon remain in fresh water their whole lives.

What is another name for kokanee salmon?

Alternate names for kokanee salmon include kokanee trout, silver trout, Kennerly’s trout, Kennerly’s salmon, little redfish, kikanning, and Walla.

Where are kokanee salmon found?

Kokanee salmon are found in freshwater lakes in the United States, Canada, Russia, and Japan.

Are kokanee salmon good to eat?

Kokanee salmon are popular fish with a relatively mild taste and a soft, rich texture.

Why do kokanee salmon turn red?

Kokanee salmon turn red during spawning to attract mates. The color change is due to a diet rich in carotenoids (pigments responsible for bright red, orange, and yellow coloration in plants and animals).

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- Fish Base, Available here: http://www.fishbase.us/summary/SpeciesSummary.php?ID=243&AT=sockeye+salmon

- IUCN Redlist, Available here: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/135301/4071001#population

- WWF, Available here: https://www.worldwildlife.org/species/pacific-salmon

- NOAA Fisheries, Available here: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/sockeye-salmon-protected

- SeafoodSource, Available here: https://www.seafoodsource.com/seafood-handbook/finfish/salmon-sockeye

- World Record Academy, Available here: https://www.worldrecordacademy.com/hobbies/largest_kokanee_world_record_set_by_Ron_Campbell_101769.htm

- NRC Research Press, Available here: https://www.zoology.ubc.ca/~etaylor/moreirataylor2015.pdf

- Canadian Science Publishing, Available here: https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/10.1139/cjfas-2019-0034

- National Library of Medicine, Available here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3352440/

- Beyond the Chicken Coop, Available here: https://www.beyondthechickencoop.com/smoked-kokanee/

- Hunter Angler Gardner Cook, Available here: https://honest-food.net/how-to-cook-kokanee/

- The Sporting Chef, Available here: https://sportingchef.com/herbed-kokanee-roasted-garlic-lemon-butter/