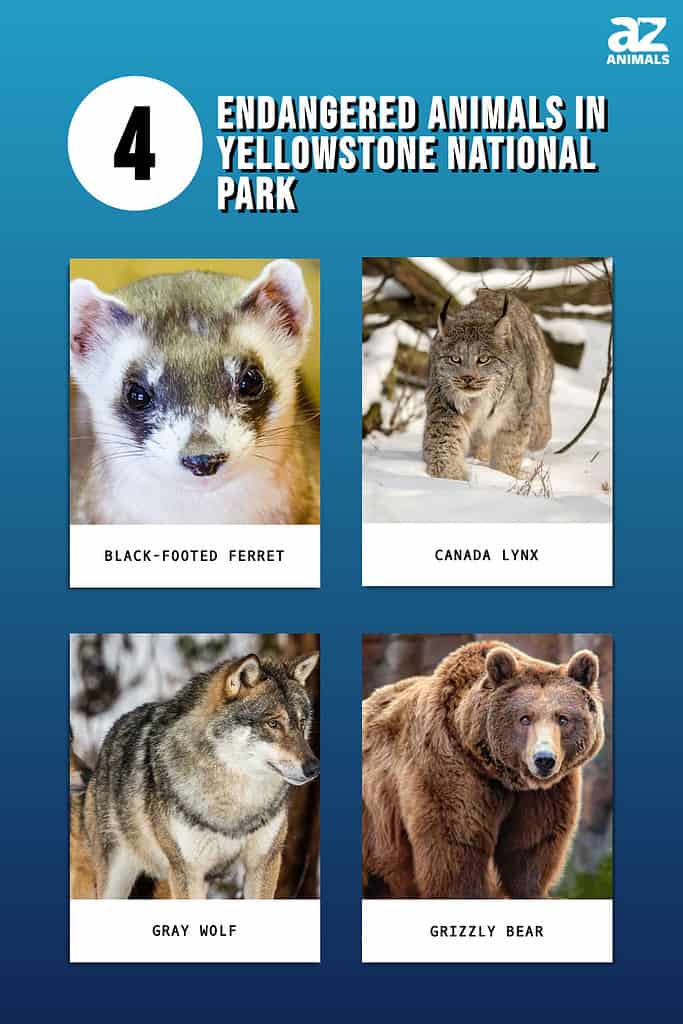

Yellowstone National Park is home to a diverse group of animals, including the largest concentration of mammals in the lower 48 states. The 4+ million annual visitors to Yellowstone enjoy wildlife encounters that cannot be replicated anywhere else in the world. However, some of these iconic Yellowstone animals are under threat. We’ll discuss four animals in the park that are either threatened or endangered. We’ll also note a few that do not have these official classifications but are considered species of concern. It’s not all bad news, though. There are some conservation success stories for Yellowstone wildlife, as well.

Yellowstone National Park is not only beautiful, but it is also an amazingly diverse ecosystem.

©NaughtyNut/Shutterstock.com

1. Black-Footed Ferret (Mustela nigripes)

The black-footed ferret is the only ferret native to North America. It is also one of the most endangered North American mammals. The black-footed ferret is native to two of Yellowstone’s three states: Montana and Wyoming. It is also native to Arizona and South Dakota.

These members of the weasel family prey almost only on prairie dogs. They also live in prairie dog burrows. The black-footed ferret population in the United States numbered around five million at the turn of the twentieth century. That number plummeted largely due to habitat loss. Huge portions of the ferret’s home and hunting grounds were converted to farmland.

The black-footed ferret was listed as endangered in 1967 under the Endangered Species Preservation Act, which was passed by the U.S. Congress one year earlier. The move may have appeared to come too late, and the black-footed ferret was declared extinct in 1979.

The black-footed ferret is the only ferret native to North America.

©Sorayot Chinkanjanarot/Shutterstock.com

A Canine’s Discovery

However, two years later, a dog in Wyoming brought a “gift” to its owner. The rancher’s dog killed a black-footed ferret. The rancher reported this to wildlife authorities. A small remaining population of black-footed ferrets was found near Meeteetse, Wyoming, in 1981.

Thanks to captive breeding and conservation efforts, the population of this flagship species began to rebound until the sylvatic plague struck. This flea-borne disease affects both black-footed ferrets and the prairie dogs they rely on. It was a devastating blow to the critically endangered ferret population. Officials from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS), National Park Service (NPS), and other agencies rushed to vaccinate ferrets and apply insecticide in prairie dog burrows to stop the fleas.

Today, the population of black-footed ferrets is between 300-400 animals. No black-footed ferrets have been documented in Yellowstone, but there is hope they may one day return. FWS has released hundreds of ferrets in two dozen locations in eight states, as well as in Canada and Mexico. Some have been released only 50 miles from Yellowstone.

Black-footed ferrets often live in abandoned prairie dog burrows.

©iStock.com/Kerry Hargrove

2. Canada Lynx (Lynx canadensis)

In 2000, FWS listed the Canada lynx as “threatened” in the lower 48 states. Yellowstone and the surrounding area is considered a critical habitat for the species’ survival.

This elusive cat’s primary prey is the snowshoe hare, especially in the winter. During the warmer seasons, it will predate rodents, rabbits, birds, red squirrels, and other small mammals.

Evidence suggests the Canada lynx lived in Yellowstone from its founding in 1872, but the population has never been high. There have only been 112 documented observations in the park. While there is only a small handful of lynx in Yellowstone, evidence continues to reveal that they are still living within the park’s boundaries.

The Canada lynx stalks its cold-weather range in search of snowshoe hares.

©Felineus/Shutterstock.com

A Small Number of Lynx Remain in Yellowstone

Several lynx were documented from 2001 to 2004. A lynx was photographed in 2007 along the Gibbon River. In 2010, a cat was spotted near Indian Creek Campground in northwest Yellowstone. Verified lynx tracks were found near the park’s Northeast Entrance in 2014.

Sightings in the park continue to be quite rare. The lynx numbers are very low in the park, and the lynx that do live in Yellowstone are notoriously elusive, solitary animals. Mollies (females) may have overlapping ranges, but toms (males) typically keep to distinct areas. These individual territories can range from 12 to over 80 square miles.

The species’ historic U.S. range included Alaska, Colorado, Idaho, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, New Hampshire, New York, Oregon, Utah, Vermont, Washington, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. The Alaskan population is healthy, but the lynx population in the lower 48 suffered from overtrapping as well as habitat loss.

Because of the cat’s secretive nature, it is difficult to determine how many lynx remain in the wild, but there are known breeding populations in northern Maine/northern New Hampshire, northeastern Minnesota, northwestern Montana/northern Idaho, north-central Washington, and western Colorado. The cats also inhabit Michigan’s Isle Royale, Washington’s Kettle Mountains, and Yellowstone’s small population.

While there are no known breeding populations of Canada lynx in Yellowstone, a small population of these cats remains in the park.

©Geoffrey Kuchera/Shutterstock.com

3. Gray Wolf (Canis lupus)

The gray wolf has long been a lightning rod for controversy. The wolf is the largest member of the Canidae (dog) family, with adults weighing up to 175 pounds. The gray wolf’s historic range covered more than two-thirds of the United States. During the 1800s, settlers moved westward, and human encounters with wolves dramatically increased. Because wolves posed a threat to livestock, they were targeted for elimination. This “predator control” was even practiced in Yellowstone after the park’s founding in 1872. Between 1914 and 1926, at least 136 wolves were killed in the park. By the end of the 1920s, all Yellowstone wolf packs had been eliminated, though single wolves were still occasionally spotted.

This obviously was a violation of the founding principles of the Yellowstone National Park Act of 1872, which stated that the Secretary of the Interior “shall provide against the wanton destruction of the fish and game found within said Park.” It was also a time when there was a clear lack of understanding of the interconnectedness of predator and prey animals in an ecosystem. By the mid-1900s, wolves had been almost entirely eliminated, not just from Yellowstone, but from the 48 states as a whole.

Gray wolf packs were eliminated from Yellowstone by 1930.

©Lillian Tveit/Shutterstock.com

Efforts to Protect and Restore Wolves Begin

In 1974, the gray wolf was classified as endangered, and recovery efforts were mandated under the Endangered Species Act. In 1995 and 1996, 31 gray wolves were relocated from western Canada to Yellowstone. Ten more wolves were relocated to the park from northwestern Montana in 1997. These relocation efforts were controversial, especially with ranchers outside of the park. Over 250 sheep and more than 40 cattle in the greater Yellowstone region were killed by wolves from 1995-2003. These numbers were actually lower than what was anticipated, though. The reintroduction efforts were scheduled to last for years but were cut short due to the surprising success of the wolves. Today, eight wolf packs roam Yellowstone National Park.

This apex species was reintroduced to Yellowstone beginning in 1995.

©Daniel Korzeniewski/Shutterstock.com

A Carousel of Delistings and Relisting

Beginning in 2008, a series of contentious gray wolf delistings and relisting as an endangered species began. The wolf was delisted from the endangered species list in Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho, only to be relisted soon afterward. Similar actions were taken in 2009.

The confusing status of the gray wolf would continue when it was delisted in Montana and Idaho in 2011. The species was then delisted in Wyoming in 2012, only to be relisted in 2014 and then delisted once again in 2017.

The wolf was delisted throughout the lower 48 states in 2020, but a 2022 court ruling reinstated the wolf to its federally protected status in much of the nation. The gray wolf is still delisted in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming, the three states where Yellowstone is found. It’s all quite complicated, but FWS published a map that helps clarify where the wolf is federally protected and where it is not.

While regulated wolf hunting seasons are now in place in the states where Yellowstone is situated, hunting and trapping remain illegal within the park’s boundaries.

4. Grizzly Bear (Ursus arctos horriblis)

The gray wolf is not the only Yellowstone animal with a confusing and controversial history as an endangered species. The grizzly bear has a similar story.

The grizzly bear was listed as a threatened species in 1975. Prior to 1800, the bear ranged from Alaska to central Mexico. The species proliferated in 18 western states in the continental U.S. Like the gray wolf, the westward expansion of European settlers invited more human/bear encounters.

The grizzly bear is one of the largest bears in the world, with some adult males weighing up to 800 pounds or more. They are also more aggressive than the smaller black bear. This stoked fear in many westward ranchers and settlers. Just like the gray wolf, the grizzly bear was seen as a threat to livestock and the further conquest of the American West.

The U.S. government implemented a bounty program that rewarded settlers for the killing of grizzly bears. The bears were trapped, poisoned, or shot wherever they were found. The goal of the bounty program was achieved as the bear was extirpated from much of its native territory.

Grizzly bears are the apex predators of Yellowstone, as seen with this bear feeding on an elk carcass along the park’s Lamar River.

©Bobs Creek Photography/Shutterstock.com

Efforts to Save the Bears Begin

By the 1930s, grizzly bears occupied just two percent of their historic range in the 48 U.S. states. When the bear was listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act in 1975, only 700-800 bears remained in the continental U.S., most of which were found in federally-protected areas such as Yellowstone. The grizzly population in Yellowstone was as low as 136 bears in the mid-1970s.

In 1993, FWS identified six official recovery zones that were critical for the grizzly’s survival. Yellowstone was one of the ecosystems listed. The efforts have turned the tide for grizzlies, which were headed toward complete extirpation in the lower 48 states. Today, there are between 1,900-2,000 grizzly bears in the contiguous United States.

Grizzly bears roam Yellowstone in increasing numbers like this young bear crossing a road in the park.

©Don Mammoser/Shutterstock.com

Another Species Is Delisted and Relisted

The grizzly bear’s status as an endangered animal began a series of confusing and controversial twists and turns in 2005, similar to those of the gray wolf. Because the recovery goals had been met for multiple consecutive years, FWS recommended delisting the grizzly bear from the endangered species list in 2005. In 2007, the grizzly population in the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem was delisted. The move was challenged through multiple lawsuits. A federal district judge overturned the delisting decision in 2009, placing the bear back on the list of threatened species. FWS appealed the decision in 2010, but an appeals court ruled the bear must remain listed as a threatened species in 2011.

In 2017, FWS removed the Yellowstone population of grizzly bears from the threatened species list. In 2018, another court overturned that decision, and the grizzly bears of Yellowstone were again relisted as threatened species. This decision remains in effect today, although new delisting efforts are reportedly under consideration. It seems that the contentious debates regarding both the gray wolf and grizzly bear are likely to continue.

Species of Concern

Along with these four endangered/threatened species, there are other animals that do not have official classification but are listed by NPS as “species of concern.”

Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos)

The golden eagle, for example, has had a stable North American population for the last 40 years. In the past, the eagle was hunted by farmers and ranchers who believed it was a threat to smaller livestock such as lambs. Current and future threats to the eagle include habitat loss, climate change, power lines, and wind energy developments. For these reasons and more, the NPS lists the golden eagle as a Yellowstone species of concern.

Along with the golden eagle, NPS also lists two other bird species, the trumpeter swan (Cygnus buccinator) and common loon (Gavia immer), as species of concern in Yellowstone.

NPS lists the golden eagle as a species of concern.

©Vladimir Kogan Michael/Shutterstock.com

North American Pronghorn (Antilocapra americana)

Along with these bird species, the North American pronghorn is a Yellowstone mammal listed as a species of special concern in Yellowstone by NPS. During the nineteenth century, as many as 35 million pronghorns resided in the American West. The influx of settlers devastated the pronghorn population, though. Ranchers saw pronghorns as competition for their livestock’s grazing lands. Much of the pronghorn’s range was converted to cropland. Pronghorns were also overhunted as a source of meat.

However, thanks to the implementation of conservation efforts, the pronghorn has rebounded to around 500,000 animals. The Yellowstone herd is still relatively small, though. Just over 500 pronghorns are known to reside in the park today. Because of the small population in the park, NPS notes that Yellowstone pronghorns are still susceptible to extirpation from random catastrophic events such as a severe winter or disease outbreaks.

Just over 500 pronghorns reside in Yellowstone, including this individual crossing a Yellowstone stream.

©Frank Fichtmueller/Shutterstock.com

Arctic Grayling (Thymallus arcticus montanus)

The arctic grayling is one of 11 native fish species in Yellowstone. While not on the endangered species list, the fish is considered a species of concern in Montana.

As its name suggests, the arctic grayling is most commonly found in northerly waters. The fish’s native range includes Alaska and much of northern Canada. The fish is only native to Michigan and Montana in the contiguous United States. The arctic grayling was extirpated in Michigan in the 1930s and nearly disappeared from Montana.

After officials observed the success of such efforts in Montana, reintroduction efforts are planned for Michigan. Arctic grayling have been reintroduced to Montana waterways, including streams that flow in Yellowstone.

Any arctic grayling caught in Yellowstone must be released unharmed and reported to park officials.

©iStock.com/Alaska_icons

Non-Native Fish

The arctic grayling disappeared from the park after non-native brook and brown trout were introduced. These trout competed with graylings for food. Brook trout also preyed on graylings.

To reintroduce arctic grayling, NPS biologists first had to rid the waterways of non-native fish. The treatment to kill off these non-native fish had to work around the nesting of common loons, which need fish to eat, as well as the spawning of the grayling and native cutthroat trout which were being reintroduced into the streams. It was quite a balancing act that required biologists to trudge through deep snow for miles to the backwaters of Yellowstone.

Their efforts are paying off, though. Arctic grayling populations are now growing and reproducing in their namesake Grayling Creek, as well as Gibbon River, Firehole River, and Wolf Lake.

Anglers who fish for grayling must use barbless hooks. The fish must be immediately released unharmed, and the catch must be reported to the park. Conversely, any angler who catches a non-native brook trout is required to kill the fish to protect the fledgling population of arctic grayling.

The reintroduction efforts of this fish have certainly been successful thus far, but the fish has a long way to go before the park reaches its goal of restoration to 20% of its historical distribution.

NPS produced a short video showing what a slow and painstaking process it is to reintroduce native fish back into their natural habitat.

Summary of 4 Amazing Endangered Animals in Yellowstone National Park

| Rank | Animal | Population in Yellowstone |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Black-footed Ferret | between 300-400 |

| 2 | Lynx | 112 documented sightings |

| 3 | Gray Wolf | 8 wolf packs |

| 4 | Grizzly Bear | 150 in the park proper, over 1,000 in the greater Yellowstone area. |

The photo featured at the top of this post is © Holly S Cannon/Shutterstock.com

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.