Spotted Lanternfly

Lycorma delicatula

The spotted lanternfly is often confused for a moth, but it’s actually a type of planthopper

Advertisement

Spotted Lanternfly Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Arthropoda

- Class

- Insecta

- Order

- Hemiptera

- Family

- Fulgoridae

- Genus

- Lycorma

- Scientific Name

- Lycorma delicatula

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Spotted Lanternfly Conservation Status

Spotted Lanternfly Facts

- Name Of Young

- Nymphs

- Group Behavior

- Solitary

- Fun Fact

- The spotted lanternfly is often confused for a moth, but it’s actually a type of planthopper

- Biggest Threat

- Humans

- Most Distinctive Feature

- The pink or tan colored wings

- Other Name(s)

- Lanternmoth

- Gestation Period

- 5 – 8 months

- Litter Size

- 20 - 60 eggs

- Habitat

- Trees

- Predators

- Wasps and other insects

- Diet

- Herbivore

- Type

- Insect

- Common Name

- Spotted Lanternfly

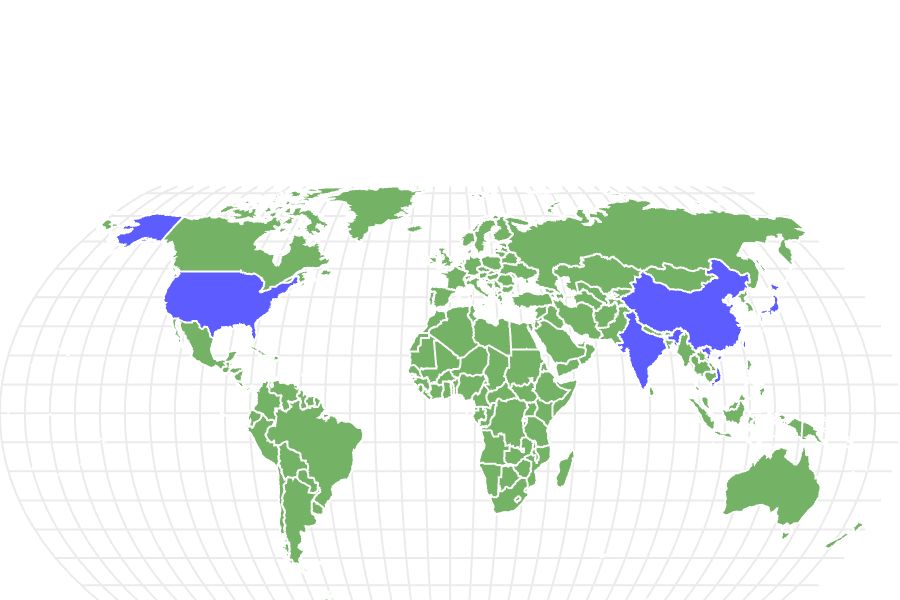

- Location

- Native to China, Vietnam, Taiwan, and India

View all of the Spotted Lanternfly images!

The spotted lanternfly is a type of small sap-eating insect that belongs to a group known as the planthoppers. Despite the name, it’s not related to flies at all but instead related to aphids, cicadas, and leafhoppers.

During its complex life cycle, the lanternfly will pass through four distinctive nymph stages before reaching full adulthood at some point in the late summer and early fall. It reproduces for a single season and then passes away.

While it remains highly mobile throughout its entire life cycle, only the adult stage actually has wings; it is capable of either hopping or flying to reach its destination. This species is considered to be a highly invasive pest in the United States because they damage plants.

5 Incredible Spotted Lanternfly Facts!

Typically, a single host tree holds a few egg masses of the lanternfly; however, in Pennsylvania, an exceptional case was documented where a tree was discovered with nearly 200 egg masses attached to its trunk.

©iStock.com/Cwieders

- The female spotted lanternfly will lay 20 to 60 eggs at some point between August and November. These egg masses are attached to the tree with a sticky adhesive substance and camouflaged from hungry predators. They will remain there for the entire winter and then hatch around May with a survival rate of around 60 to 90%.

- A single host tree normally contains a few lanternfly egg masses, but one tree in Pennsylvania was found to contain nearly 200 egg masses on its trunk.

- The spotted lanternfly can travel several miles over the course of its life. It can hitch a ride on vehicles by jumping into windows or the backs of trucks.

- If there are too many nymphs on a tree, then they will start to fight each other for access to food. Once challenged to a fight, the approaching nymph will either flee or attempt to mount the other one to show dominance.

- The scientific name for each nymph stage in its life cycle is an instar. Each instar is separated by a molt when the insect replaces its entire skin.

Evolution and Origins

The Tree of heaven is among the preferred hosts for this invasive species, which poses a risk to a wide range of trees, including fruit-bearing, ornamental, and woody trees.

©Peter Coffey/Shutterstock.com

Originating from China, the Spotted Lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula) was initially identified in Pennsylvania in September 2014 and has since become established in the region.

This invasive species poses a threat to various trees, including fruit, ornamental, and woody trees, with a particular preference for the tree of heaven.

Following a period of overwintering, the eggs of the spotted lanternfly hatch during the spring season, giving rise to small nymphs adorned with black bodies and white spots.

As they progress through their growth stages, the nymphs transition to a vibrant red color while retaining their characteristic black and white spots, ultimately maturing into striking, winged adults.

Species, Types, and Scientific Names

The scientific name of the spotted lanternfly is Lycorma delicatula. Delicatula is thought to mean delicate or dainty in Latin. It belongs to the Fulgoridae family, along with other species of lanternflies.

Appearance: How to Identify Them

With a pink or tan hue, the adult spotted lanternfly exhibits distinctive features such as two pairs of sizeable wings, spanning approximately one to one and a half inches in length.

©vm2002/Shutterstock.com

The adult spotted lanternfly is characterized by two pairs of large wings, measuring about an inch to an inch and a half long, with a pink or tan hue.

The upper wings are covered in small black spots about two-thirds of the length, followed by a brick or striped pattern at the ends. Both sexes have a yellow abdomen with black stripes, but only the females have a red-colored plate near the end of the abdomen. They also have short orange antennae with needle-like tips.

Whereas the adult is often mistaken for a moth, the nymph stage of the life cycle actually resembles a tick. There are four distinctive nymph stages. The first three stages all look fairly similar to each other with a black body and white spots. By the fourth stage, however, it has developed red markings on its back to complement the white spots. It grows progressively bigger with each stage.

Habitat: Where to Find Them

Parts of southern China, Vietnam, Taiwan, and India serve as the native habitat for the spotted lanternfly.

©iStock.com/arlutz73

The spotted lanternfly is native to parts of southern China, Vietnam, Taiwan, and India. While it has been found to inhabit more than 70 different species of plants, including fruit trees, ornamental trees, and vines, the adult’s favorite host plant in its native habitat is the tree of heaven. It greatly prefers trees with smooth bark so it can more easily climb and lay its eggs.

Unfortunately, the Tree of Heaven is considered to be an invasive species in many parts of the world. This has made it possible for the spotted lanternfly to invade habitats such as Japan, South Korea, and the United States.

The insect was first sighted in the United States in 2014 (though it may have been introduced even earlier). Berks County, Pennsylvania, just to the northwest of Philadelphia, was the first known location. From there it spread to New York, Delaware, Maryland, NJ, Virginia, and elsewhere.

Both egg masses and adults are sometimes accidentally transported between cities and states on common outdoor items such as firewood, motor homes, and recreational vehicles. Check your state’s quarantine map to find out if the spotted lanternfly is a problem in your area.

Diet: What Do They Eat?

The spotted lanternfly is an herbivore. While the adults tend to focus on a single host tree, the nymphs are attracted to many different plants, including maples, poplars, apple trees, and grapevines.

What eats the spotted lanternfly?

The spotted lanternfly has few natural predators in the United States. In its native habitat, it is preyed upon by wasps and other insects. Their bad taste and toxic byproduct can act as a form of deterrence to stop most predators.

What does the spotted lanternfly eat?

The spotted lanternfly feeds on the sap of its host tree. When the insects are present in enough numbers, this feeding can put significant stress on its host. It also produces a substance called honeydew as waste, which can attract both pests and mold to a tree. These factors can sometimes combine to significantly damage or even kill its host. Perhaps because they eat sap, they do not have strong mouth parts to bite.

Prevention: How to Get Rid of Them

Due to its classification as a detrimental invasive species, several locations in the United States, such as Pennsylvania and New Jersey, advise taking measures to manage and mitigate the populations of the spotted lanternfly.

©Jay Ondreicka/Shutterstock.com

Since the spotted lanternfly is considered to be a harmful invasive species, many places in the United States, including Pennsylvania and NJ, recommend making an effort to control their populations.

When they’re still in the egg stage between the fall and spring, the masses can be easily scraped off trees (or any other surfaces they appear on) with a knife or other sharp-edged instrument. The eggs should be sealed in a plastic bag or placed into a sanitizer or alcohol to destroy them.

Once they hatch, nymphs and adults are much harder to control. They must be individually killed by hand or with an insecticide or chemical treatment. One alternative method is to cut down nearly all high-risk host plants on your property. You can leave a few trees behind to act as traps so you can destroy the remaining populations.

Are They Harmful to Humans?

Luckily, spotted lanternflies are not known to be harmful to humans, just the plants they feed on. Control of adult lanternflies can prove an annoyance, as trying to swat these bugs is no easy feat. Adults are able to fly or jump away at great distances, out of your reach.

View all 293 animals that start with SSpotted Lanternfly FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

How many legs does the spotted lanternfly have?

The spotted lanternfly has six legs, the same as any other insect.

How do you identify spotted lanternflies?

The adult spotted lanternflies are most often accidentally mistaken for a moth when their wings are extended. The telling characteristic is the tan or pink colored wings with black spots and a kind of striped pattern near the end. Their wings are also folded at rest. The nymph stages look completely different; they kind of resemble ticks. The telling detail is the black or red exoskeleton with white spots.

Are spotted lanternflies dangerous?

The spotted lanternfly is not dangerous to humans, and they’re not known to bite, but they can destroy or damage the plants on which they feed.

How do you get rid of spotted lanternflies?

When the spotted lanternfly lays its eggs, you can scrape the entire egg mass off the tree and destroy it. When it has grown into a nymph or an adult, you can kill them by hand or use an insecticide or chemical treatment. If you can afford to, it might be a good idea to remove some of the common host plants from your property or at least leave a few behind to act as traps. The traps will attract the insects so you can apply a chemical treatment or kill them.

What eats spotted lanternfly?

The spotted lanternfly is preyed upon by wasps and other insects, but the harsh taste often repels many other kinds of predators, including birds and frogs.

What do you do if you see a spotted lanternfly?

If you live in the United States, there are several things you can do to stop the spread of spotted lanternfly populations. Most states actually recommend killing them on sight. Pennsylvania and NJ have also placed several counties on their map in a lanternfly quarantine zone. Quarantine means some regulations are in place to restrict the movement of certain items, including tree parts, firewood, grape vines, nursery stocks, packing materials, landscaping items, and common outdoor items. Check a quarantine map to see if it applies to your county.

What do spotted lanternflies do to humans?

Spotted lanternflies are actually harmless to humans. They’re not known to bite or sting very often.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- Animal Diversity Web, Available here: https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Lycorma_delicatula/

- Cornell CALS, Available here: https://nysipm.cornell.edu/environment/invasive-species-exotic-pests/spotted-lanternfly/spotted-lanternfly-ipm/biology-life-cycle-identification-and-dispersion/

- Ortho, Available here: https://www.ortho.com/en-us/library/bugs/how-kill-control-spotted-lanternfly