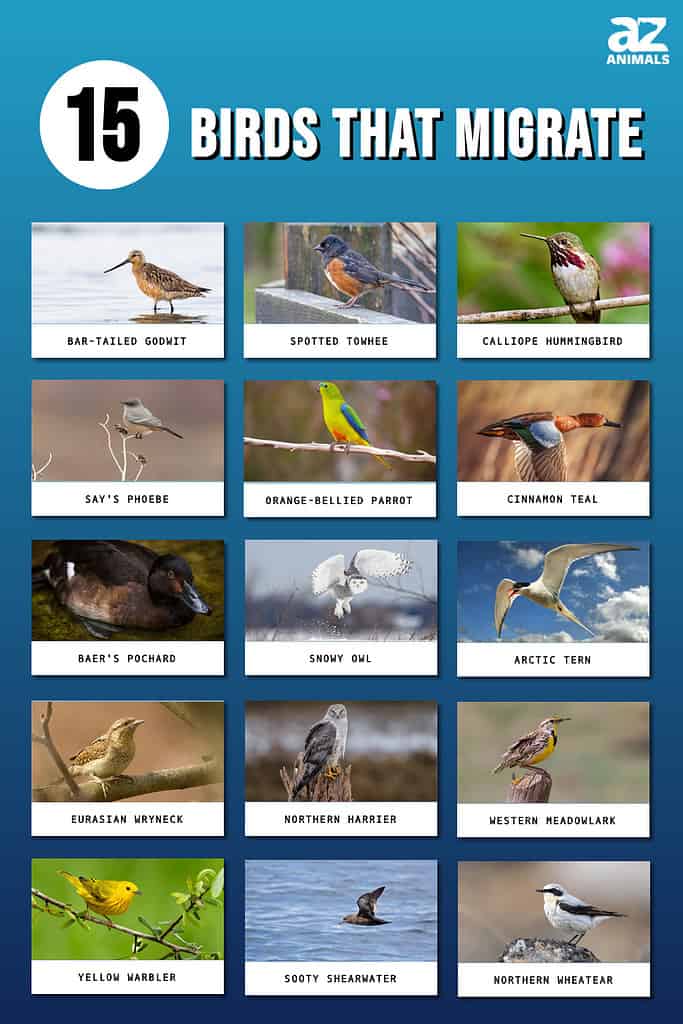

Approximately 40% of all birds migrate, whether it’s a quick trip to a warmer location or a long, grueling journey. Birds migrate, like other migratory species, in search of habitats with greater supplies or for breeding purposes.

The abundance of food and other resources, as well as the environment, affect how and when they choose to migrate. These animals are all first-class passengers, whether it be because of their migration routes, some of which are extraordinarily long, or the fact that they are endangered species.

Why Do Birds Migrate?

Birds migrate in order to shift from low-resource areas to high-resource areas or vice versa. The two main items sought after are food and places to build nests. Birds that breed in the Northern Hemisphere typically move northward in the springtime to reap the benefits of the abundance of nesting sites, expanding insect populations, and blossoming plants.

The birds once more migrate south as winter draws near and the number of insects and other food sources decreases. Escape from the cold is a driving force, but many species, like hummingbirds, can tolerate subfreezing temperatures if they have access to enough food.

Short-distance migration patterns probably developed from a very simple need for food, but long-distance migration patterns have far more complex beginnings. They have undergone extensive evolution and are, at the very least, somewhat impacted by the biology of the birds.

What Dictates Migration?

They also consider responses to the surroundings, geography, food availability, the duration of daylight, and other factors. Combinations of shorter days, colder temperatures, shifting food supplies, and genetic predisposition can all lead to migration.

The migratory birds go through a phase of agitation every spring and autumn, continually fluttering toward one side of their cage, as humans who have maintained cage birds have observed for decades.

Birds that migrate annually can fly thousands of kilometers, frequently following the same path with little variation. Birds in their first year frequently go alone on their very first migration. Despite having never seen it before, they manage to locate their winter residence and return the following spring to their original birthplace.

Let’s go over some of the most well-known birds that migrate!

Bar-tailed Godwit

The bar-tailed godwit makes the longest non-stop flight of any bird.

©iStock.com/rockptarmigan

With a non-stop migration of almost 7,000 miles, the bar-tailed godwit has the longest migratory of any land bird. These birds make the approximately week-long journey from New Zealand to their breeding locations in Alaska every year over the open sea.

Before going on to Alaska, they have a single stop on their summer journey at the Yellow Sea. Bar-tailed godwits return to Europe and Asia for the summer after the mating season. Bar-tailed Godwits gain weight before their travel by consuming additional food that is retained as fat in order to endure this lengthy, uninterrupted flight.

Spotted Towhee

The Spotted Towhee is a common Towhee species.

©iStock.com/jamesvancouver

It’s likely that the first time you hear this long-tailed, round-bodied sparrow, it will be through different sounds. The Spotted Towhee is likely to catch your ear, whether it is humming its chup-chup-zheee melody from the tops of the trees in pursuit of a companion or through its loud meewww sounds from deep within a bush.

The dark “cloak” that adult males and females wear covers their heads, throats, backs, and wings all the way down to their tails. Males are nearly black with clearly reddish-brown eyes, while females and newborns tend to be browner.

Their name comes from the white patches on their top wings. Their tummy is completely white, and their flanks are a deep chestnut brown color. If you witness one take flight, keep an eye out for the white outer flash.

Calliope Hummingbird

The Calliope Hummingbird is the smallest bird native to the United States and Canada. It has a western breeding range, mainly from California to British Columbia.

©MTKhaled mahmud/Shutterstock.com

The tiniest long-distance migratory birds on the globe are Calliope Hummingbirds. These tiny hummingbirds travel far for their size. Each year, they undertake the 5,000-mile roundtrip journey from central and southern British Columbia, traveling south over the Pacific Coast and the American West until they reach Mexico, where the total population, which is thought to number 4.5 million, spends their winter.

They nest on trees 40 feet in the air and breed in the highlands at elevations of 4,000 feet and higher.

Say’s Phoebe

These birds frequently wave their tails up and down while sitting, just like other phoebe species.

©Frank Fichtmueller/Shutterstock.com

This flycatcher is slowly making its way back to the western rangelands. Say’s Phoebes frequently live alone and in silence. Nonetheless, their sweet, wistful morning pee-ur choruses are among the first to welcome you in the wee hours of the morning.

These birds frequently wave their tails up and down while sitting, just like other phoebe species. You’ll be able to identify them by their hunting techniques. One involves a quick flight from a bush or fencepost, a quick hold five feet above the ground, and then a dive to snag an insect.

The other tactic involves waiting for the first spring insect hatches to cross western rivers, which typically happens as the temperature begins to increase. If these birds attempt to find cover inside your home, don’t be concerned.

Orange-bellied Parrot

In order to migrate, the orange-bellied parrot covers only a 300-mile distance from its summer breeding places to its winter homes.

©Agami Photo Agency/Shutterstock.com

With less than 30 remaining in the wild, the orange-bellied parrot, one of just three migratory parrots, is in grave danger. With 100 wild and captive orange-bellied parrots born during the 2020 mating season, an Australian recovery initiative is exhibiting signs of being successful.

In order to migrate, these parrots only cover a 300-mile distance from their summer breeding places in southwest Tasmania to their winter home in the marshlands and dunes close to the South Australia and Victoria coastline.

Cinnamon Teal

The Cinnamon Teal and other bird species depend on freshwater wetlands as a healthy breeding habitat.

©Wirestock Creators/Shutterstock.com

One of the first visual attractions of spring waterfowl migration is the Cinnamon Teal. This species searches out low, marshy layover areas like lakes, vernal wetlands, and mudflats as it travels between breeding grounds farther north.

To eat seeds and aquatic foliage, as well as bugs and zooplankton, this dipping duck flips over. Watch the wings during preening or flight for an eye-catching band of solid-colored feathers (called a speculum). Impressive colors on the upper wing include powder blue, white, and green, more predominately shown on males.

Due to their propensity to hybridize, both of these species’ field marks should be studied in order to distinguish between the two species and any possible hybrids. The Cinnamon Teal and some other bird species depend on freshwater wetlands as a healthy breeding habitat, and the Western Rivers Initiative works carefully to safeguard these areas.

Baer’s Pochard

There are only between 150 and 700 healthy adults left of the Baer’s pochard, making it a critically endangered species.

©GypsyPictureShow/Shutterstock.com

Although there have been instances of breeding in Mongolia and North Korea, eastern Russia and central China are where Baer’s pochard is most commonly found. The breeding territories of the pochard, which formerly occurred throughout all of northern China, have considerably decreased.

The ducks migrate south during the winter, perhaps to northeastern India, eastern and southern China, Bangladesh, Thailand, and Myanmar.

Sadly, there are only between 150 and 700 healthy adults left of the Baer’s pochard, making it a critically endangered species. The birds are especially at risk in the winter because of hunting. Their decrease has also been exacerbated by the degradation and destruction of wetlands in their nesting sites.

Snowy Owl

The snowy owl is more nomadic than migratory, departing its usual habitat at all times of the day and night to forage for prey.

©Jim Cumming/Shutterstock.com

Snowy owl migratory patterns are rather elusive because they change from year to year. When winter hits their homes in northern Canadian and the Arctic, they migrate south, and occasionally they get as far south as Florida and Texas. The snowy owl is more nomadic than migratory, departing its usual habitat at all times of the day and night to forage for prey.

Arctic Tern

Each year, the Arctic tern travels an amazing 25,000 miles one way from the Arctic to the Antarctic.

©ASPhoto2013/Shutterstock.com

Take a peek at the Arctic tern’s migration if you want to experience a truly long journey. Although populations of these little birds can also be spotted in Massachusetts and England, they are found in the Arctic Circle.

To reach its mating habitats along the Antarctic coast, the animal must travel a difficult and protracted distance. Each year, the Arctic tern travels an amazing 25,000 miles one way from the Arctic to the Antarctic.

Eurasian Wryneck

Eurasian wrynecks frequently use other woodpeckers’ nesting holes rather than digging their own since they have smaller bills than other woodpeckers.

©Yuriy Balagula/Shutterstock.com

The extensive range of the Eurasian wryneck includes Central Asia and Europe. They travel between 1,500 and 3,000 miles during their migration, depending on the starting place and endpoint. The birds spend their winters in Africa, India, and Southeast Asia and their summers in Western Asia and Europe.

Eurasian wrynecks frequently use other woodpeckers‘ nesting holes rather than digging their own since they have smaller bills than other woodpeckers.

Northern Harrier

The northern harrier avoids major bodies of water and likes to stay over broad lands when migrating.

©Harry Collins Photography/Shutterstock.com

There is only a single species of harrier found in North America, the northern harrier. This hawk-family member bird of prey ranges widely from Alaska and some of the most northern regions of Canada to the southern United States.

These birds that live more north will travel as far as Venezuela and Colombia to spend the winter, whereas those in the southern U.S. typically remain there because there is no need to migrate when they are already in regions with stable temperatures. The northern harrier avoids major bodies of water and likes to stay over broad lands when migrating.

Western Meadowlark

Postponing any mowing until August is advised if you notice meadowlarks in your gardens or backyards.

©iStock.com/Gary Gray

Is there a song that more plainly heralds the arrival of sunnier days and months than Western Meadowlarks’ colossal songs as they build and protect mating grounds? This species is a welcome reappearance for those of us who live in meadows, pasturelands, or oak-savannas.

The songs and activities of this ground-nesting species are very amazing, and their bright yellow bellies and breasts provide color to the morning sun shining through a fence post or phone pole. When flying, look for their straight-line flight and somewhat short tail with white outer feathers.

Postponing any mowing until August is advised if you notice meadowlarks in your gardens or backyards. This species may deposit its eggs in the grass and hatch one to two clutches of young by mid-summer. These actions will also help pollinators in the interim.

Yellow Warbler

The most widespread warbler species in the Americas is the yellow warbler.

©Agami Photo Agency/Shutterstock.com

Hedgerows, undergrowth, and woodlands are starting to see the appearance of warblers. The Yellow Warbler is one such species that favors mature foliage close to rivers and wetlands. Whirring chips or reprimanding sweet notes from deep inside willows are examples of brief encounters.

Similar to several other warblers, adults have a canary yellow underside and pale green feathering on the back. Red coloring can be seen running through the breasts of males. Adult birds have short black bills and sharp black eyes that are skilled at easily picking insects out of vegetation. This species needs our assistance in lowering nighttime light levels to prevent accidents with man-made objects because it is a tiny, long-distance traveler.

Sooty Shearwater

Sooty shearwaters are prevalent in both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, and they fly thousands of miles each year.

©iStock.com/hstiver

The sooty shearwater has a very unusual migration length for a common seabird. Sooty shearwaters are prevalent in both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, and they fly thousands of miles each year. Although the Pacific shearwaters move 40,000 miles annually, the Atlantic birds only cover roughly 12,000 miles. Just the non-breeding population of sooty shearwaters remains behind on these migrations every year.

Northern Wheatear

The northern wheatear makes the longest migration of any songbird.

©iStock.com/Banu R

The northern wheatear has a wide breeding range, breeding all throughout Eurasia and along the northern coast of North America. The northern wheatear migrates to sub-Saharan Africa throughout the winter, despite its point of origin. This flight frequently takes place over ice and seas, which are rare conditions for songbirds.

Those birds that leave from Alaska travel 9,320 miles to get to Africa, compared to 4,600 miles for those that leave from eastern Canada. They repeat the process to return after the wintering period.

Common Types of Migration

Have you ever witnessed a bird’s migration? Many birds migrate south to warmer climates to spend the winter when the season shifts. Migration is the term for this. Thousands of birds migrate each year to avoid the cold. They move to their breeding areas in the spring. Here are some of the most common types of migration!

Altitudinal

The term “vertical migration,” sometimes known as “altitudinal migration,” refers to the movement from mountain ranges to lower altitudes. During the cold season, birds that nest in high mountains during the summer move to low lowlands. They don’t cover much ground. Temperatures and food supplies can fluctuate significantly over a distance of only 900 feet.

Altitudinal migrants include Siberian willow ptarmigans, violet-green swallows from Great Britain, and Andean grebes from Argentina. Both bush chats and Eurasian woodcocks travel from upper to lower elevations.

Partial

A bird species’ partial migration is when some of its individuals do not migrate. Although a few of them move, others do not. Generally, a specific species of bird that is native to the north migrate to the south. The others, though, who already reside in warmer climates, remain there throughout the year.

For instance, blue jays from Canada and the north of the United States move south to interact with the stationary populations in the south. Additionally, spoonbills, coots, bluebirds, titmice, and finches are partial migrants as well.

Latitudinal

Latitudinal migration refers to movement from north to south or south to north, for instance, from the Arctic to the tropics and vice versa. For nourishment and refuge, birds from the northern temperate regions migrate to the south. Some southern bird species travel to the north to reproduce.

The majority of birds in North America migrate along these routes. American golden plovers, Arctic terns, puffins, Canada geese, bald eagles, and numerous other species are among the most prevalent. Penguins and other flightless birds migrate in a similar manner by swimming.

Longitudinal

The longitudinal migration is the transition from one direction to another, from the Atlantic coast to the Rocky Mountains. Due to the geographic characteristics of Europe, birds from that continent tend to wander longitudinally.

For instance, California gulls typically breed in Utah. However, they move westward toward the Pacific Coastline to spend the winter there. Additionally, throughout the winter, European starlings, which are native to east and west Europe and Asia, move to the Atlantic coast.

| Name of Bird | |

|---|---|

| Bar-tailed Godwit | 7,000 miles from New Zealand to Alaska |

| Spotted Towhee | From Canada to Guatemala |

| Calliope Hummingbird | Central and southern British Columbia to Mexico |

| Say’s Phoebe | From New England and Nova Scotia to southern Texas, Mexico, and Central America |

| Orange-bellied Parrot | 300 miles from southern Tasmania to South Australia and Victoria |

| Cinnamon Teal | Southwestern Canada and western United States to Mexico, Caribbean, and South America |

| Baer’s Pochard | Eastern Russia and northern and central China to northeast India, eastern and southern China, Bangladesh, Thailand, and Myanmar |

| Snowy Owl | Northern Canada and Arctic to as far as Florida and Texas |

| Arctic Tern | 25,000 miles from Arctic to Antarctica |

| Eurasian Wryneck | 1,500-3,000 miles from western and central Asia and Europe to Africa, India, and southeast Asia |

| Northern Harrier | Alaska and northern Canada to Venezuela and Columbia (Those in the southern US stay there) |

| Western Meadowlark | From Canada and northern United States to Gulf Coast, coastal plains of Mexico, and Baja |

| Yellow Warbler | Central and northern North America to Central America and northern South America |

| Sooty Shearwater | 12,000-40,000 miles: Atlantic birds go from Antarctic to Arctic; Pacific birds go in a figure-eight pattern from New Zealand to Japan, to Alaska, to California and back. |

| Northern Wheatear | 9,320 miles-4,600 miles from Eurasia, northern coast of North America, and Alaska to Sub-Saharan Africa. |

The photo featured at the top of this post is © Jim Cumming/Shutterstock.com

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.