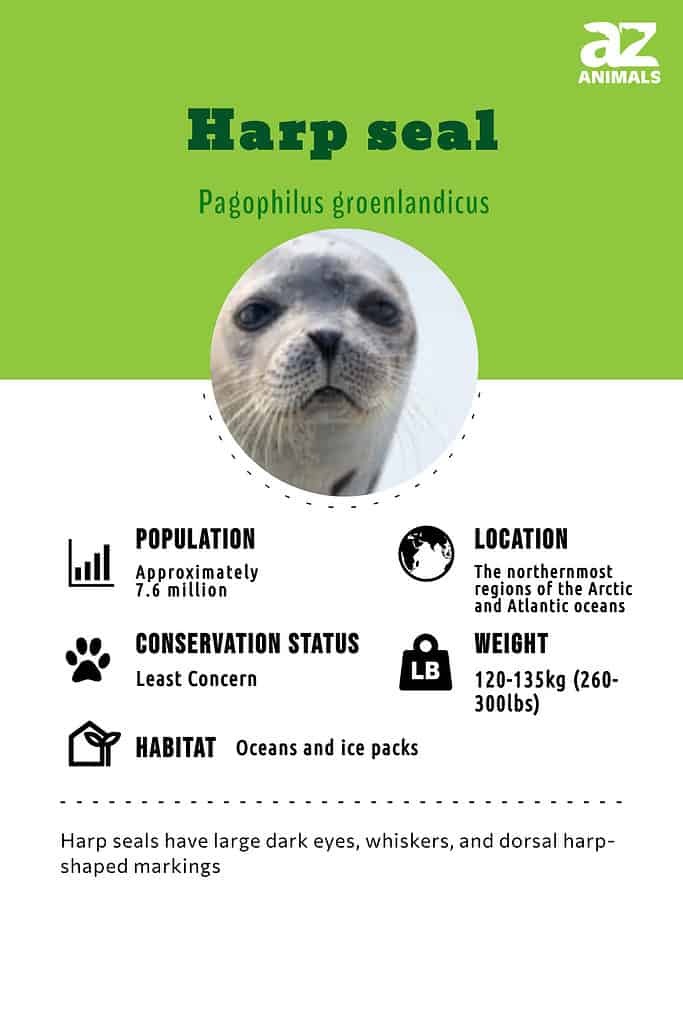

Harp Seal

Pagophilus groenlandicus

The harp seal can migrate up to 3,000 miles every year

Advertisement

Harp Seal Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Mammalia

- Order

- Carnivora

- Family

- Phocidae

- Genus

- Pagophilus

- Scientific Name

- Pagophilus groenlandicus

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Harp Seal Conservation Status

Harp Seal Facts

- Prey

- Fish and marine invertebrates

- Name Of Young

- Pups

- Group Behavior

- Solitary/Colony

- Fun Fact

- The harp seal can migrate up to 3,000 miles every year

- Estimated Population Size

- Up to 7.6 million

- Biggest Threat

- Climate change

- Most Distinctive Feature

- The harp-shaped black mark on the back

- Other Name(s)

- Saddleback seal or Greenland seal

- Gestation Period

- 11.5 months

- Litter Size

- 1

- Habitat

- Oceans and ice packs

- Predators

- Killer whales, polar bears, walruses, and sharks

- Diet

- Carnivore

- Type

- Mammal

- Common Name

- Harp Seal

- Number Of Species

- 1

- Location

- North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans

Harp Seal Physical Characteristics

- Color

- Grey

- Black

- White

- Skin Type

- Fur

- Weight

- 120-135kg (260-300lbs)

- Height

- 120-135kg (260-300lbs)

- Length

- 1.5-2m (5-6.5ft)

- Age of Sexual Maturity

- 5.5 years

- Age of Weaning

- 10 to 12 days

View all of the Harp Seal images!

The harp seal is awkward and clumsy on land. But in the water, it is an elegant swimmer and an expert predator.

These are fairly common animals in the oceans of the extreme north. Named after the black harp-shaped markings on the back, the harp seal is a marvel of evolution, thanks to the many incredible adaptations it needs to survive in an inhospitable environment, including blubber and flippers. The harp seal is a member of the true earless seal family. This is to distinguish them from fur seals, sea lions, and walruses.

4 Incredible Harp Seal Facts!

- There are two recognized subspecies of harp seals, one in the North Atlantic and another in the White Sea. While they don’t interbreed at all due to their vast geographical distances, there are also no real anatomical or morphological differences between them.

- Adult seals molt, or shed their fur, every spring.

- A thick layer of blubber just beneath the skin is a necessary adaptation that helps the harp seal to stay warm in the frigid waters of the north. The blubber also helps streamline the body to make it more efficient for swimming.

- One of the more amazing facts is that seals have extremely flexible bodies. They can almost fold the upper half completely backwards.

You can check out more incredible facts about harp seals.

Scientific Name

Harp seals are believed to be closely related to ribbon seals and gray seals

©Dolores M. Harvey/Shutterstock.com

The scientific name of the harp or saddleback seal is Pagophilus groenlandicus. The name roughly translates from the ancient Greek to mean an ice-lover (Pagophilus) from Greenland (groenlandicus). This species is the only living member of its genus, but as mentioned previously, it is a member of the true earless seal family, the Phocidae. The closest living relatives are probably the ribbon seal and the grey seal.

Evolution

As the Oligocene period drew to an end, the oceans became cooler resulting in an abundance of food which resulted in mammals being drawn to them.

However, it wasn’t until 12 million years later that the ancestor of the pinnipeds emerged on the scene. Known as Puijila darwini (discovered by Natalia Rybczynski), it lived in the Arctic Circle. The creature preferred freshwater to saltwater unlike its descendants which are also capable of handling the latter.

The earliest pinniped somewhat resembled a seal, although it had the body of an otter and four stout limbs with which it walked and swam. It also had webbed toes and was a skilled swimmer. However, it lacked the adroitness of its descendants in the water.

Appearance

Harp seals can grow as long as 5 feet and weigh up to 300 lbs

©Dolores M. Harvey/Shutterstock.com

The harp seal can be identified as a member of the true earless seal family by the torpedo-shaped body and the presence of short front flippers, long hind flippers, large claws, short fur, and the lack of external ear flaps. They also have a long, tapered snout and a flat but wide head.

The defining feature of this species is the black harp-shaped mark on the back and the hood on the head. This is surrounded by light gray fur, sometimes punctuated by black spots. Most harp seals measure between 5 and 6 feet long and weighs about 260 to 300 pounds. Males are generally larger on average than females and have more prominent markings. Some females never even develop the well-defined harp markings for which this species is known.

Behavior

Harp seals live communally at their breeding grounds in winter but hunt individually at their feeding grounds in summer

©AleksandrN/Shutterstock.com

Harp seals undertake a long migration every year in search of resources and mating opportunities. They sometimes move up to 3,000 miles round trip between their winter breeding grounds, where they molt, mate, and raise young, and their summer feeding grounds, where they stock up on food for the year. The breeding colonies feature an immense concentration of seals, with up to 2,000 of them per square kilometer. It is not entirely known whether the colony has a distinct social organization or hierarchy to it, but when they reach their feeding grounds in the early summer, the seals then become solitary hunters and have minimal interactions with other members of the same species.

Harp seals make a number of different sounds to communicate with each other, including clicks, trills, growls, and chirps. While they’re not very vocal on the ice, they will make numerous underwater calls to attract mates and coordinate activities. The mother will also make a shrill call if her baby is threatened by a nearby predator. Pups likewise emit a yelling sound to alert the mother to their presence.

Like all members of the true seal family, the harp seal has evolved numerous adaptations for its marine lifestyle. Its hind feet extend directly behind the body and are unable to rotate forward. In order to move on the land, it crawls or scoots forward on its belly. As poor and cumbersome as it is on land, however, the harp seal is an excellent swimmer in the water. Thanks to their oxygen-rich blood, harp seals can spend over 20 minutes beneath the surface, diving down to a depth of more than 1,300 feet.

They have excellent vision and hearing underwater, but their sense of smell is comparatively poor and underdeveloped; they cannot smell at all underwater, because their nostrils are closed in order to prevent water from entering their bodies. The whiskers (also called vibrissae) also provide a well-developed sense of touch and vibration.

Habitat

Harp seals exist in three unique populations which can be found in Canada as well as northern and western Europe

©iStock.com/slowmotiongli

The harp seal can be found in the frigid waters of the North Atlantic and the Arctic Oceans, hanging out near packs of floating ice. There are three distinctive populations, each with a unique habitat and migratory route. One Canadian population breeds in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and then travels north to the Hudson Bay, off the coast of Baffin Island, to feed in the early summer. Another population breeds near the small island of Jan Mayen and then travels north toward Svalbard and Greenland to feed. The final population, which is essentially its own subspecies, migrates between the White Sea, just off the coast of Russia, and the Barents Sea to the north. Stray seals have been found traveling as far south as Germany, Spain, and the United Kingdom.

Predators and Threats

Harp seals face numerous threats in the wild, including predators, vessel strikes, entanglements in fishing gear or debris, oil spills and chemical contaminations, and the melting ice from climate change. Harp seals are hunted by humans for fur, oil, and meat, especially in the tradition of native Arctic peoples. Thanks to its remote location, these threats haven’t yet posed an existential danger. However, as the climate warms, there are signs already that seals are struggling to cope with the lack of seal ice. Moreover, as the Arctic becomes more hospitable to humans, there could be more conflicts and negative interactions in the future.

What eats the harp seal?

Polar bears are known to prey on harp seals

©Vladimir Gjorgiev/Shutterstock.com

Harp seals are preyed upon by killer whales, polar bears, walruses, and Greenland sharks. The seal’s natural speed and agility, plus its ability to easily transition from land to sea (and vice versa), offer useful defenses against hungry predators. Camera teams have sometimes captured footage of a desperate seal narrowly avoiding the clutches of a killer whale by climbing onto floating ice. Killer whales, too, will sometimes attempt to knock the seals off the ice by creating waves.

What does the harp seal eat?

The harp seal is a carnivorous predator. By one count, it has been known to consume some 67 fish species and 70 species of marine invertebrates. The composition of their diet depends on location and the time of the year, but popular prey items include krill, herring, cod, and flat fish.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Harp seals give birth after 11.5 months and pups weigh about 25 lbs when they are born

©Vladimir Melnik/Shutterstock.com

The harp seal mating season takes place every winter. It isn’t known how many mates each seal will have per year: they’ve been observed to have anywhere between one and several mates at a time. Even females have been seen with multiple male partners. Regardless, seal reproduction is full of interesting facts. The male initiates courtship with several elaborate rituals to attract a mate’s attention. He may chase the female, wave his paw at her, or make bubbles and noises from beneath the ice where she has made an entry hole nearby. The competition for mates is fierce. The males will engage in fights by splashing and biting each other. There is also speculation that the female may choose her mate based on his anatomy.

After copulating, the female has a long gestation period of 11.5 months – though four months of this is due to delayed implantation. The fertilized egg literally waits in suspended animation until the female is ready for pregnancy after she has returned to the feeding grounds. The female will give birth to a single baby on the ice right near open water. Weighing about 25 pounds, the pups are born with tufts of white hair, sometimes stained yellow with amniotic fluid. This white fur absorbs sunlight and keeps the baby warm. After about three weeks, it transforms into a silver-white coat with irregular black spots; at this point, the seal is called a bedlamer. The pups are raised on the mother’s high-fat milk, which enables them to develop their layers of protective blubber.

This entire reproductive cycle operates on very tight timing. When the first pup is fully weaned, about 10 to 12 days after it’s born, the female will be ready to mate again with another male. At the same time, she will continue to teach the pup valuable survival skills and provide care for the next few weeks without any assistance or input from the father. Pup mortality is quite high during this time, and many do not survive to their full lifespan. While the pup is functionally independent at four weeks, it won’t become sexually mature until about 5.5 years old. Males will begin reproducing at around eight years of age, while females wait until they’re about 10 years old. The harp seal’s typical lifespan in the wild is somewhere between 20 and 35 years.

Population

About 7.6 million harp seals are believed to exist

©iStock.com/Valery Kudryavtsev

The harp seal is currently classified as a species of least concern by the IUCN Red List. They’ve estimated there are about 4.5 million mature harp seals remaining in the wild, divided across three distinctive populations. Other estimates put the number as high as 7.6 million seals total. In the past, the population has fluctuated between 1 million and 9 million. Thanks to a reduction in hunting and accidents, the population numbers are now increasing.

View all 104 animals that start with HHarp Seal FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

What is a harp seal?

The harp seal (also known as a saddleback seal) is a member of the true seal family. It is easily identified by the presence of black markings on the head and back. Harp seals spend the vast majority of their time in the water, but they also come ashore on ice packs to breed, molt, and raise their pups.

Are harp seals carnivores, herbivores, or omnivores?

The harp seal’s diet is completely carnivorous.

Where do harp seals live?

Harp seals divide their time between the water and the ice floes in the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans.

What do harp seals eat?

Harp seals mostly consume fish and marine invertebrates.

What are harp seal predators?

Harp seals are preyed upon by killer whales, polar bears, walruses, and Greenland sharks.

Is a harp seal a mammal?

Yes, the harp seal is actually a member of the same order, Carnivora, as foxes, wolves, bears, and raccoons. While it may not necessarily look like any other type of mammal, the seal still bears all the usual hallmarks of the mammalian class, including the milk production, thermoregulation, fur, and parts of the skeletal structure that distinguish it from other classes. There’s been some debate about the true evolutionary origin of all Pinnipeds (seals, sea lions, and walruses), but they probably evolved from a weasel-like ancestor some 15 to 20 million years ago.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- Animal Diversity Web, Available here: https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Pagophilus_groenlandicus/

- NOAA Fisheries, Available here: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/harp-seal

- IUCN Red List, Available here: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/41671/45231087