Ivy Bee

Colletes hederae

Female ivy bees line their brood cells with a waterproof fungi-resistant secretion!

Advertisement

Ivy Bee Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Arthropoda

- Class

- Insecta

- Order

- Hymenoptera

- Family

- Colletidae

- Genus

- Colletes

- Scientific Name

- Colletes hederae

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Ivy Bee Conservation Status

Ivy Bee Facts

- Prey

- N/A

- Main Prey

- N/A

- Name Of Young

- larvae

- Group Behavior

- Solitary

- Fun Fact

- Female ivy bees line their brood cells with a waterproof fungi-resistant secretion!

- Estimated Population Size

- Undetermined

- Biggest Threat

- habitat loss, pesticide

- Most Distinctive Feature

- vividly banded (striped) black and yellow abdomen

- Distinctive Feature

- hair covered thorax

- Other Name(s)

- ivy mining bee

- Gestation Period

- 5-7 days

- Temperament

- mild

- Wingspan

- 0.6 - 0.8 inches (15 to 20 mm)

- Training

- N/A

- Optimum pH Level

- N/A

- Incubation Period

- up to 9 months

- Age Of Independence

- at emergence

- Age Of Fledgling

- N/A

- Average Spawn Size

- 1-12 eggs

- Litter Size

- N/A

- Habitat

- sandy/loamy soil near ivy

- Predators

- birds, spiders, other insects

- Diet

- Herbivore

- Average Litter Size

- N/A

- Lifestyle

- Diurnal

- Favorite Food

- Ivy nectar

- Type

- Colletes hederae

- Common Name

- ivy bee

- Special Features

- beautifully striped black and yellow abdomen

- Origin

- Italy

- Number Of Species

- 200

- Location

- Europe

- Slogan

- N/A

- Group

- N/A

- Nesting Location

- underground burrows; loose mortar in walls

- Age of Molting

- various times throughout larval stage

Ivy Bee Physical Characteristics

- Color

- Brown

- Yellow

- Black

- Gold

- Orange

- Skin Type

- Exoskeleton

- Lifespan

- 3 weeks - 1 year

- Weight

- less than 1 ounce

- Height

- 0.1-0.2 inches

- Length

- 0.4 - 0.5 inches (10 to 12 mm) females; 0.3-0.4 inches (8 to 10 mm) males

- Age of Sexual Maturity

- At emergence

- Age of Weaning

- N/A

- Venomous

- No

- Aggression

- Low

View all of the Ivy Bee images!

Have you heard the buzz? There’s a new kid in town, and its name is the ivy bee (Colletes hederae). Since its discovery in Italy in 1993, this charming little bee has captured the hearts of entomologists and nature lovers alike with its vibrant stripes and efficient foraging habits. But don’t be fooled by its cute appearance – this bee is a true powerhouse when it comes to pollinating ivy flowers!

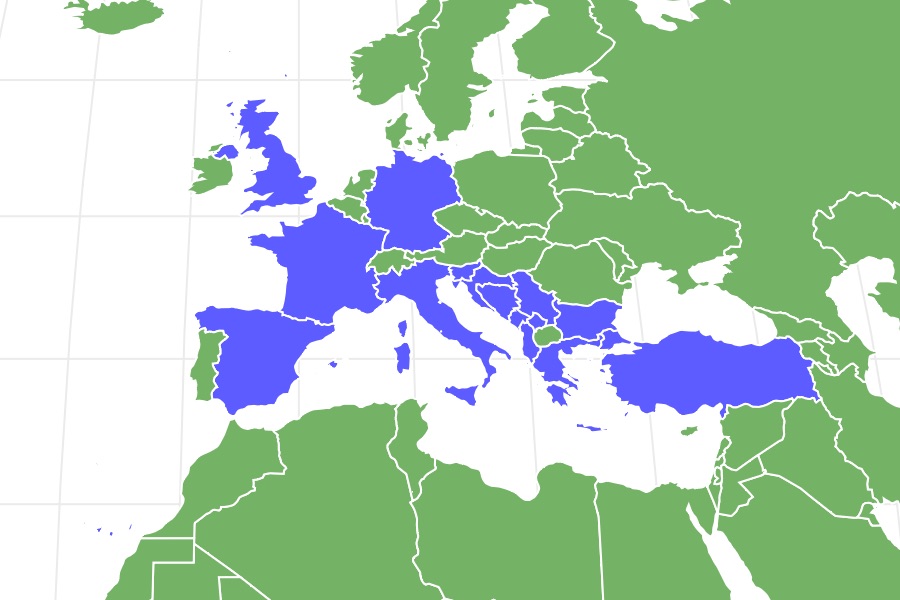

Since their initial discovery, ivy bees have made their presence known in other parts of Europe, including Italy, Greece, Spain, and the Balkans. However, in recent years, this species has also been observed in France, Germany, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. The warming climate may be contributing to the range expansion of Colletes hederae. Colletes hederae are one of over 200 species in the genu Colletes, which are renowned for their solitary nesting habits. Using their incredible burrowing abilities, these bees create tunnels in the so, lining them with a waterproof fungi-resistant secretion. Keep reading to learn more about this fascinating newly-discovered species!

Ivy Bee: The Discovery

Konrad Schmidt and Paul Westrich are the entomologists who first discovered and named Colletes hederae in 1993. They found this species in Italy, where it was observed to be exclusively foraging on the flowers of ivy plants. These researchers were particularly intrigued by this behavior, as the ivy plant blooms in the late autumn and early winter when most other flowers have already withered. Since its discovery, Colletes hederae has become renowned for its pollination of ivy, which is a crucial food source for many insects and birds during the winter months. Since their discovery, the species has been observed throughout Europe.

Ivy Bee: Scientific Name

The scientific binomial name Colletes hederae is derived from a combination of the genus name Colletes and the species name hederae. Colletes is a Greek word that translates to one who glues. This is in reference to this family of bees’ habit of lining their brood cells with a waterproof coating. The species-specific hederae refers to the bee’s foraging behavior. Ivy (Hedera helix), is the primary source of nectar and pollen for this species. Therefore, the name Colletes hederae can be translated as the ivy-loving bee that glues. Bees in the family Colletes are sometimes called cellophane bees, plasterer bees, or polyester bees. Their common nicknames are derived from the females’ habit of coating their brood cells with a waterproof, fungi-resistant secretion.

Appearance

Also called the ivy mining bee, Colletes hederae is a medium-sized bee with a distinctive banded (striped) appearance. The adult female Ivy bee measures between 0.4 – 0.5 inches (10 to 12 mm) in length, while the males are slightly smaller at 0.3-0.4 inches (8 to 10 mm). Their average wingspan is between 0.6 – 0.8 inches (15 to 20 mm). Ivy bees have bands of yellow and black or orange and black stripes covering their bodies. Their head, thorax, and abdomen are covered with dense hairs (setae), which give them a fuzzy appearance. Females can be easily distinguished from males by their larger size and the presence of a dense patch of hairs on the underside of their abdomen. This patch of hairs, known as the scopa, is used to carry pollen back to the nest.

An ivy bee’s head, thorax, and abdomen are covered with dense hairs which give them a fuzzy appearance.

©Peter J. Traub/Shutterstock.com

Ivy Bee: Behavior

Colletes hederae are solitary bees. They do not live in colonies or have castes like honey bees (Apis). Instead, each female Ivy bee constructs her own underground nest consisting of individual brood cells. independently. Ivy bees emerge from their underground nests in late summer or early autumn, to coincide with the blooming of ivy flowers, which are their primary source of nectar and pollen.

Ivy bees are unique in that they are one of the few bee species that emerge so late in the season to specifically forage on ivy flowers, which typically bloom in the late autumn and early winter months. As a result, Ivy bees have a relatively short active season compared to other bee species, with adult bees usually living for only a few weeks to a few months before they die off for the year. Their offspring overwinter as pupae, snug, safe, and dry in individual brood cells that have been provisioned by their mother.

Dufour’s Gland

Dufour’s gland is an organ found in a variety of insects that performs a variety of functions. The function of the secretions varies among species and orders. Dufour’s gland secretes a combination of chemicals and pheromones. Depending on the specific insect and the situation these secretions are used to waterproof brood cells, feed larvae (when mixed with pollen and nectar), or communicate.

In females, the gland produces a sticky, waterproof substance that the bees use to line the walls of the brood cells they construct. This waterproof coating helps to keep the cells dry and prevents mold and other pathogens from growing inside. Female Ivy bees carefully apply this substance to each brood cell to create a waterproof seal, ensuring that their offspring are protected from moisture during development.

©IanRedding/Shutterstock.com

Ivy bees are highly efficient foragers and can collect large amounts of pollen in a short amount of time. Male Ivy bees can often be seen flying low over the ground in search of females with which to mate. Ivy bees are not known to be aggressive towards humans and will generally only sting if provoked or threatened.

Ivy Bee: Habitat

Colletes hederae are primarily found in open, sunny habitats such as coastal cliffs, quarries, and south-facing slopes. They prefer areas with well-draining soils, such as sandy or loamy soils, where they can easily construct their underground nests. Ivy bees are most commonly found in Southern and Central Europe and have recently expanded their range to parts of the UK, and the Balkans in Eastern Europe.

In addition to ivy plants, which are their primary food source, Ivy bees may also forage on other flowering plants in their habitat, such as heather (Calluna vulgaris), thistle (Silybum marianum), and dandelion (Taraxacum).

Ivy Bee: Diet

Colletes hederae are specialist foragers, meaning that they have a strong preference for a particular type of flower, in this case, ivy (Hedera helix). Ivy is the primary source of nectar and pollen for Ivy bees, and they are highly efficient at collecting these resources from ivy flowers. However, Ivy bees may occasionally forage on other flowering plants in their habitat, particularly in early autumn when ivy flowers have not yet bloomed. They have been observed visiting a variety of flowering plants, including heather, thistles, and dandelions. Although Ivy bees may forage on other plants, they are still highly dependent on ivy for their survival, and their populations are closely linked to the availability of ivy flowers in their habitat.

Predators

Colletes hederae face a range of predators in their environment. Many bird species, such as woodpeckers and swallows, will prey on ivy bees. Birds may target ivy bees both as adults and as larvae in their nests. Several species of wasps are known to prey on Colletes hederae One example is the cuckoo wasp (Chrysis ignita), which lays its eggs in Colletes hederae nests, where the larvae feed on the ivy bee larvae.

Some species of ants may raid ivy bee nests and steal their larvae and food stores. The ants may also kill adult bees that come in contact with their colonies. Spiders are common predators of many insects, including Colletes hederae. Orb-weavers (Araneidae), capture ivy bees in their webs, while crab spiders (Thomisidae) ambush them as they forage for food.

Threats

Colletes hederae face several threats to their survival, including:

- Habitat loss and fragmentation: The destruction and fragmentation of their natural habitats due to urbanization, land-use changes, and agricultural practices can reduce the availability of suitable nesting sites and food sources for Colletes hederae.

- Climate change: Changes in temperature and precipitation patterns can affect the timing of plant flowering and the emergence of Colletes hederae adults, leading to mismatches in timing and reduced reproductive success.

- Pesticides: The use of pesticides in agriculture and horticulture can have harmful effects on Colletes hederae and other pollinators by reducing the availability of food and damaging their health.

- Invasive species: The introduction of non-native plants and animals into Colletes hederae habitats can compete with native species and alter the balance of the ecosystem.

- Disease and parasites: Like many other bee species, Ivy bees are susceptible to a range of diseases and parasites, which can weaken their immune system and reduce their reproductive success.

Population and Conservation Status

The population data on Ivy bees is limited and largely focused on specific regions or habitats where they are known to occur. In general, Ivy bees are not considered to be rare or endangered, although they are a relatively recent addition to the bee fauna of Europe and their distribution is still expanding.

In the UK, for example, the Ivy bee was first recorded in 2001 and has since been found in increasing numbers in Southern and Central England. Similarly, in Southern Europe, the population of Ivy bees appears to be increasing in many areas, with records from Spain, Italy, and Greece, indicating that they are becoming more common.

The conservation status of Ivy bees has not been formally assessed on a global scale. However, based on available information, Ivy bees are not currently considered to be at risk of extinction or in need of specific conservation measures. They have not been identified as a conservation priority by major organizations such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Ivy Bee: Lifecycle

In late summer or early autumn, ivy bees emerge from their underground nests. The females begin to excavate new nest burrows, while the males are hanging around waiting on the females to show them some interest. The burrows are typically located in bare or sparsely vegetated soil or in the mortar joints of old walls and buildings. Once the nest burrow is complete, the female Ivy bee begins collecting pollen and nectar from ivy flowers to create a food store for her offspring.

She then lays a single egg on top of the food store and seals the cell with secretions from her Dufour’s gland. when the eggs hatch (5-7 days), the resulting larvae feed on the food stores left by their mother. The larva grows and molts several times before spinning a cocoon and pupating. The pupa undergoes metamorphosis inside the cocoon, transforming into an adult bee over the winter months. The new adult ivy bee emerges the following autumn beginning the cycle anew.

View all 39 animals that start with IIvy Bee FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

What do ivy bees look like?

Also called the ivy mining bee, Colletes hederae is a medium-sized bee with a distinctive banded (striped) appearance. The adult female Ivy bee measures between 0.4 – 0.5 inches (10 to 12 mm) in length, while the males are slightly smaller at 0.3-0.4 inches (8 to 10 mm). Their average wingspan is between 0.6 – 0.8 inches (15 to 20 mm). Ivy bees have bands of yellow and black or orange and black stripes covering their bodies. Their head, thorax, and abdomen are covered with dense hairs (setae), which give them a fuzzy appearance. Females can be easily distinguished from males by their larger size and the presence of a dense patch of hairs on the underside of their abdomen. This patch of hair, known as the scopa, is used to carry pollen back to the nest.

Do ivy bees live in colonies?

No! Ivy bees are solitary bees. They do not live in colonies or have castes like honey bees (Apis). Instead, each female Ivy bee constructs her own underground nest consisting of individual brood cells. independently. Ivy bees emerge from their underground nests in late summer or early autumn, to coincide with the blooming of ivy flowers, which are their primary source of nectar and pollen.

Where do ivy bars live?

Ivy bees are found along coastal cliffs, quarries, and south-facing slopes. They prefer areas with well-draining soils, such as sandy or loamy soils, where they can easily construct their underground nests. Ivy bees are most commonly found in Southern and Central Europe and have recently expanded their range to parts of the UK, and the Balkans in Eastern Europe.

What is Dufour's gland?

Dufour’s gland is an organ found in a variety of insects that performs a variety of functions. The function of the secretions varies among species and orders. Dufour’s gland secretes a combination of chemicals and pheromones. Depending on the specific insect and the situation these secretions are used to waterproof brood cells, feed larvae (when mixed with pollen and nectar), or communicate. Ivy bees use their Dufour’s gland to weatherproof their nests.

Why do ivy bees emerge so late in the year?

Ivy bees emerge precisely when they are supposed to! The timing of their emergence is based to coincide with the blooming of ivy, which is a late bloomer. Timing is everything for both the bees and the ivy.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- bwars.com, Available here: https://www.bwars.com/content/colletes-hederae-mapping-project

- zoologicalbulletin.de, Available here: https://zoologicalbulletin.de/BzB_Volumes/Volume_53_1_2/027_036_BZB53_1_2_Bischoff_Inge_et_al.PDF

- pensoft.net, Available here: https://bdj.pensoft.net/article/66112/

- buzzaboutbees.net, Available here: https://www.buzzaboutbees.net/Colletes-plasterer-bees.html

- ncsu.edu, Available here: https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/colletid-bees-plasterer-bees-cellophane-bees-and-polyester-bees

- flawildflowers.org, Available here: https://www.flawildflowers.org/know-your-native-pollinators-polyester-bees/

- bumblebeeconservation.org, Available here: https://www.bumblebeeconservation.org/ivyminingbee/

- asknature.org, Available here: https://asknature.org/strategy/dufours-gland-creates-waterproof-nest-linings/

- pensoft.net, Available here: https://jhr.pensoft.net/article/1649/

- researchgate.net, Available here: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Geographic-range-expansion-of-Colletes-hederae-in-Western-Europe-between-1994-and-2010_fig2_259315452