Ashy Mining Bee

Andrena cineraria

Ashy mining bees deposit their eggs between 2-8 inches underground.

Advertisement

Ashy Mining Bee Facts

- Prey

- N/A

- Main Prey

- N/A

- Name Of Young

- larvae

- Group Behavior

- Solitary

- Fun Fact

- Ashy mining bees deposit their eggs between 2-8 inches underground.

- Estimated Population Size

- Undetermined

- Biggest Threat

- habitat loss

- Most Distinctive Feature

- ashy colored hairs on their thorax and face.

- Distinctive Feature

- Burrowing behavior

- Other Name(s)

- the Danubian miner bee or the grey mining bee.

- Gestation Period

- 3-5 days

- Temperament

- docile

- Wingspan

- 0.4-0.6 inches

- Training

- N/A

- Optimum pH Level

- N/A

- Incubation Period

- 3-5 days

- Age Of Independence

- 6 weeks

- Age Of Fledgling

- N/A

- Average Spawn Size

- 6-12

- Litter Size

- N/A

- Habitat

- orchards, backyard gardens

- Predators

- birds, lizards, snakes, other insects

- Diet

- Herbivore

- Average Litter Size

- 6-12

- Favorite Food

- Nectar of fruit tree blossoms

- Type

- Andrena cineraria

- Common Name

- Ashy mining bee

- Special Features

- Hairy faces

- Origin

- Europe

- Number Of Species

- 1500

- Location

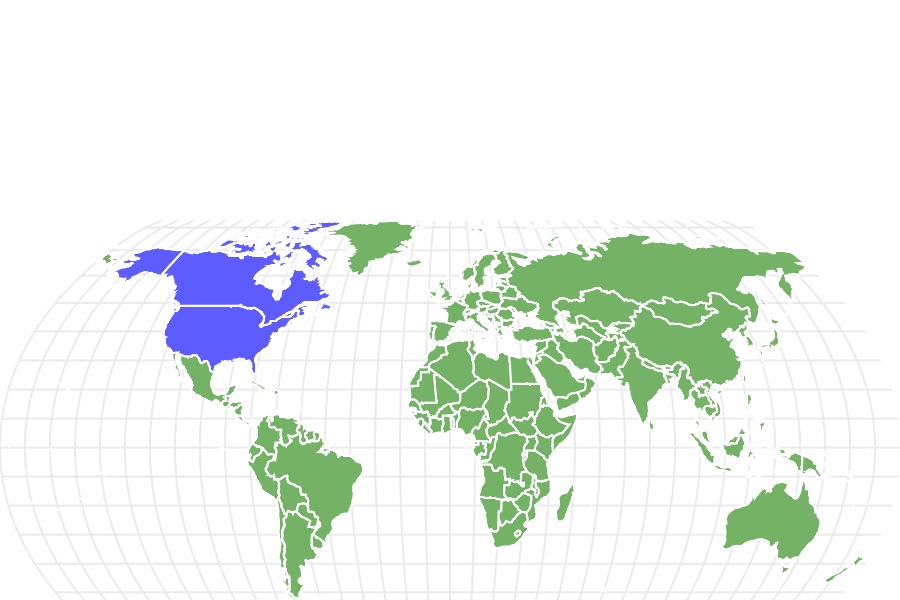

- Europe, North America

- Average Clutch Size

- -23

- Slogan

- N/A

- Group

- N/A

- Nesting Location

- subterranean burrows

- Age of Molting

- various time throughout larval stage

Ashy Mining Bee Physical Characteristics

- Color

- Black

- White

- Light Grey

- Skin Type

- Exoskeleton

- Lifespan

- 3 weeks - I year

- Weight

- less than 1 ounce

- Height

- 0.20 inches

- Length

- 0.35-0.5 inches

- Age of Sexual Maturity

- 6 weeks

- Age of Weaning

- N/A

- Venomous

- No

- Aggression

- Low

View all of the Ashy Mining Bee images!

Andrena cineraria, the ashy mining bee, is a species of solitary bee commonly known as the Danubian miner bee or the grey mining bee. The species is native to Europe. It is also found in North America, where it is an introduced species, and thus not as widespread as it is in its native range. Mining bees nest in individual burrows in the ground. Ashy mining bees do not produce honey, but they are important pollinators. Keep reading to learn more about this solitary species.

Five facts about Ashy Mining Bees

- Ashy mining bees will retreat to their nests, sealing the entrance behind them, when they’re finished foraging for the day or in inclement weather.

- They construct their burrows (nests) on south-facing slopes.

- Ashy mining bees burrow between 2-8 inches underground to lay their eggs

- Male ashy mining bees do not build nests.

- Andrena cineraria do not live in colonies

Scientific Name

Andrena cineraria is the binomial scientific name for ashy mining bees. Andrena is a genus of solitary bees and cineraria, which is Latin for ashes, refers to the color of the bee which is white-to-gray or ash-colored. Species’ binomial scientific names are usually derived from a physical characteristic or geographic location. Containing over 1,500 species, Andrena is one of the largest genera of insects.

Appearance

Andrena cineraria is a small to medium-sized bee, typically measuring about 0.35 – 0.5 inches (9-12 mm) in length, with wingspans of 0.4-0.6 inches (10-13 mm). Females are larger than males, which is typical of bees generally. The bees are distinctive for the gray-to-white, ash-colored hairs that cover their shiny blue-black bodies. Males have tufts of ashy hairs on their faces and on all of their legs, while females only sport hairs on their front legs. These hairs are called setae (singularly seta). Setae are stiff, bristle-like hairs that are multi-functional. They provide insulation and are used for carrying pollen and sensing the environment.

Ashy mining bees have compound eyes. Compound eyes are made up of many individual photoreceptor units, called ommatidia (singularly ommatidium), that work together to form a single image. Each ommatidium is responsible for capturing light and transmitting a signal to the brain, and the combined information from all the ommatidia produces a mosaic image. This type of eye design allows insects like bees to have a wide field of vision and sensitivity to movement, but with limited resolution compared to the human eye.

Ashy mining bees are distinctive for the gray-to-white, ash-colored hairs that cover their shiny blue-black bodies.

©IanRedding/Shutterstock.com

Behavior

Andrena cineraria is a solitary bee species. Females construct and provision their own nests independently. They do not live in colonies, though sometimes this species will aggregate. Aggregations may appear to be swarms to untrained eyes. However, ashy mining bees are harmless and do not swarm. These solitary bees will congregate when obtaining mud or clay from which they will construct their nests, and they occasionally build individual nests in close proximity. However, they do not live in traditional colonies. The proximity is the result of suitable nest sites rather than community. The female bees dig burrows between 2-8 inches (5-20 cm) deep in well-drained soil or clay. Each burrow contains no more than a dozen (12) individual cells. The female provisions each cell with nectar and pollen, which will provide the nutrients her brood will need. Once supplied, miner bees deposit an individual egg in each cell.

The female miner bee uses her mandibles to gather small particles of soil or clay, tightly packing them around the edges of the cell to form a secure seal. The seal protects the developing larvae inside, minimizing fluctuations in temperature and humidity within the cells. Once the cells have been sealed, the female ashy mining bee is relieved of her responsibilities. Andrena cineraria are generally a docile and non-aggressive species, and will not sting unless provoked. They are active foragers, visiting a variety of flowering plants to collect nectar and pollen. The species is considered to be a key pollinator of several important crops and wildflowers. Ashy mining bees, as pollinators, support biodiversity in their habitats. Ashy mining bees are active in spring and summer.

Habitat

Andrena cineraria live in a variety of habitats including meadows, hedgerows, and cultivated fields/orchards. In its native range, it is common and widely distributed. The species has also been introduced to North America, where it has been reported in several states and Canadian provinces.

Introduced species are species that are intentionally or accidentally moved to a new location outside of their natural range, either by human activity or natural processes. An introduced species may establish a population and become established in its new location, or it may struggle to survive. It is not known precisely how ashy mining bees were introduced to North America but they have been in evidence in the U.S. and Canada for over 100 years. In both its native and introduced ranges, the ashy mining bee prefers well-drained soil, from which the females construct burrows in which to lay their eggs. The species is common near agricultural areas, especially orchards, as well as backyard gardens.

Diet

Ashy mining bees are herbivores. They forage on a wide variety of flowering plants, including shrubs, wildflowers, and cultivated crops. They are especially fond of a variety of blossoms of fruit-bearing trees including apple, cherry, and plum. The bees do not feed directly on the fruit of the trees, instead visiting the blossoms, and gathering nectar and pollen, which provide energy and nutrition for them and their offspring. The pollination of fruit trees by Andrena cineraria helps to increase the production and quality of fruit crops. Ashy mining bees are effective pollinators. They also forage on a variety of wildflowers and ornamentals. Ashy mining bees are drawn to brightly colored flowering plants like delphinium, iris, azalea, dahlia, and roses.

Predators and Threats

Predators

Ashy mining bees are preyed upon by a range of predators, including birds, reptiles, and other insects, depending upon their stage of development. In their adult form, ashy mining bees fall victim to a variety of bird species. Thrushes, swifts, mockingbirds, and woodpeckers will all nosh on an ashy mining bee if given the opportunity. Snakes, like the Eastern garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis sirtalis), and lizards, like the Western fence lizard (Sceloporus occidentalis), will hang around nesting sites hoping for a quick snack. Parasitoid wasps, like the Darwin wasp (Ichneumonidae), and the chalcid wasp (Chalcididae) lay their eggs on or inside the eggs or larvae of Andrena cineraria, eventually killing them.

Threats

Ashy mining bees face an array of threats from habitat loss and climate change to agricultural chemicals and disease. The loss of natural and introduced habitats is a major threat to the species as it reduces the availability of suitable nesting sites and foraging opportunities Urban sprawl and suburban development continue to usurp mining bee habitats, with no recourse for the species. Changes in temperature and precipitation patterns, as well as the timing of seasonal events such as flowering, can negatively affect ashy miner bees.

Herbicides and Pesticides

Agricultural chemicals like insecticides and herbicides are harmful to all bee species, including ashy mining bees. The use of glyphosate, a toxic chemical in pre-emergent herbicides, has been restricted in several European nations, including Belgium, France, and Germany. The chemical is thought to negatively affect bees’ digestive systems, causing colony-wide illness. Neonicotinoids are synthetic pesticides widely introduced in the late 20th century. Though this new class of pesticides was originally hailed as safe, research now suggests that nicotine-based pesticides are in fact toxic to bees and other beneficial insects. These toxic chemicals remain with the plants for years, as well as seeping into the ground, and contaminating streams and other bodies of water. Studies are determining that bee populations across all species are declining at a rapid and concerning rate. it is important to minimize these threats through conservation and education.

Conservation Status and Population

The ashy mining bee is listed as a species of least concern by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. The last time the species was assessed was in May of 2014. In the intervening years, research has determined that bee populations across all species are in decline. It follows that ashy mining bee populations are declining. However, the population of this widespread species is not well-researched or documented.

Lifecycle

The lifecycle of Andrena cineraria consists of four stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult.

The female ashy miner bee burrows 2-8 inches (5-20 cm) into the ground where she creates a nest of 10-12 individual cells. She supplies each cell with the nectar and pollen that her offspring will require to grow and pupate. With the cells have been prepared, the female mining bee deposits a single egg in an individual cell. After 3-5 days, the eggs hatch the larvae feed on the provisions of nectar and pollen stored in the cell. The larva undergoes several instars or molts as it grows.

Once the larva has finished feeding, it spins a cocoon and pupates within the cell where it will overwinter. During the pupal stage, the larva undergoes metamorphosis and transforms into an adult bee.

When the pupal stage is complete, the adult bee emerges from the cell and begins to forage for nectar and pollen. As a solitary bee species, ashy mining bees are not part of a colony. The adult bees are most active in spring and summer when they are seen visiting a variety of flowering plants to collect food.

The entire lifecycle of this species from egg to adult takes almost a full year, as the adult bees do not emerge until the following spring. After emerging as an adult, the bee will live for several weeks to several months. During this time, the bees will mate, forage for food with which to provision the next generation of cells, and deposit their eggs. Once their eggs have been deposited in the prepared cells, female ashy mining bees are free to forage.

Up Next

View all 194 animals that start with AAshy Mining Bee FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

What does introduced species mean?

Introduced species are species that are intentionally or accidentally moved to a new location outside of their natural range, either by human activity or natural processes. An introduced species may establish a population and become established in its new location, or it may struggle to survive. It is not known precisely how ashy mining bees were introduced to North America but they have been in evidence in the U.S. and Canada for over 100 years.

What do ashy mining bees eat?

Ashy mining bees are herbivores. They forage on a wide variety of flowering plants, including shrubs, wildflowers, and cultivated crops. They are especially fond of a variety of blossoms of fruit-bearing trees including apple, cherry, and plum. The bees do not feed directly on the fruit of the trees, instead visiting the blossoms, and gathering nectar and pollen, which provide energy and nutrition for them and their offspring. The pollination of fruit trees by Andrena cineraria helps to increase the production and quality of fruit crops. Ashy mining bees are effective pollinators. They also forage on a variety of wildflowers and ornamentals. Ashy mining bees are drawn to brightly colored flowering plants like delphinium, iris, azalea, dahlia, and roses.

What do ashy mining bees look like?

Ashy mining bees are small to medium-sized bees, typically measuring about 0.35 – 0.5 inches (9-12 mm) in length, with wingspans of 0.4-0.6 inches (10-13 mm). Females are larger than males, which is typical of bees generally. The bees are distinctive for the gray-to-white, ash-colored hairs that cover their shiny blue-black bodies. Males have tufts of ashy hairs on their faces and on all of their legs, while females only sport hairs on their front legs. These hairs are called setae (singularly seta). Setae are stiff, bristle-like hairs that are multi-functional. They provide insulation and are used for carrying pollen and sensing the environment.

What sorts of animals prey on ashy mining bees?

Ashy mining bees are preyed upon by a range of predators, including birds, reptiles, and other insects, depending upon thetr stage of development. In their adult form, ashy mining bees fall victim to a variety of bird species. Thrushes, swifts, mockingbirds, and woodpeckers will all nosh on an ashy mining bee if given the opportunity. Snakes, like the Eastern garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis sirtalis), and lizards, like the Western fence lizard (Sceloporus occidentalis), will hang around nesting sites hoping for a quick snack. Parasitoid wasps, like the Darwin wasp (Ichneumonidae), and the chalcid wasp (Chalcididae) lay their eggs on or inside the eggs or larvae of Andrena cineraria, eventually killing them.

What threats do ashy mining bees face?

Ashy mining bees face an array of threats from habitat loss and climate change to agricultural chemicals and disease. The loss of natural and introduced habitats is a major threat to the species as it reduces the availability of suitable nesting sites and foraging opportunities Urban sprawl and suburban development continue to usurp mining bee habitats, with no recourse for the species. Changes in temperature and precipitation patterns, as well as the timing of seasonal events such as flowering, can affect the behavior and reproduction of ashy miner bees.

Agricultural chemicals like insecticides and herbicides are harmful to all bee species, including ashy mining bees. Neonicotinoids are synthetic pesticides widely introduced in the late 20th century. Though this new class of pesticides was originally hailed as safe, research now suggests that nicotine-based pesticides are in fact toxic to bees and other beneficial insects. These toxic chemicals remain with the plants for years, as well as seeping into the ground, and contaminating streams and other bodies of water.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- umm.edu, Available here: https://uwm.edu/field-station/mining-bee/

- nih.gov, Available here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8324941/

- wiki.com, Available here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashy_mining_bee

- wiki.org, Available here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrena

- bumblebeeconservation.org, Available here: https://www.bumblebeeconservation.org/ashy-mining-bee/

- moraybeedinosaurs.co.uk, Available here: http://www.moraybeedinosaurs.co.uk/solitary.html