Canvasback

Aythya valisineria

They're the largest diving duck in North America!

Advertisement

Canvasback Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Aves

- Order

- Anseriformes

- Family

- Anatidae

- Genus

- Aythya

- Scientific Name

- Aythya valisineria

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Canvasback Conservation Status

Canvasback Facts

- Prey

- Plants, mussels, insects, snails

- Main Prey

- Plants

- Group Behavior

- Group

- Sociable

- Fun Fact

- They're the largest diving duck in North America!

- Estimated Population Size

- 700,000

- Biggest Threat

- They're the largest diving duck in North America!

- Most Distinctive Feature

- Sloped bill

- Distinctive Feature

- Bright red eye

- Wingspan

- 31 to 35 inches

- Predators

- Large birds and raptors, foxes, coyotes, minks, ermines

- Diet

- Omnivore

- Lifestyle

- Colony

- Social

- Group

- Sociable

- Favorite Food

- wild celery

- Common Name

- canvasback

- Special Features

- bright red eyes on males

- Number Of Species

- 1

- Location

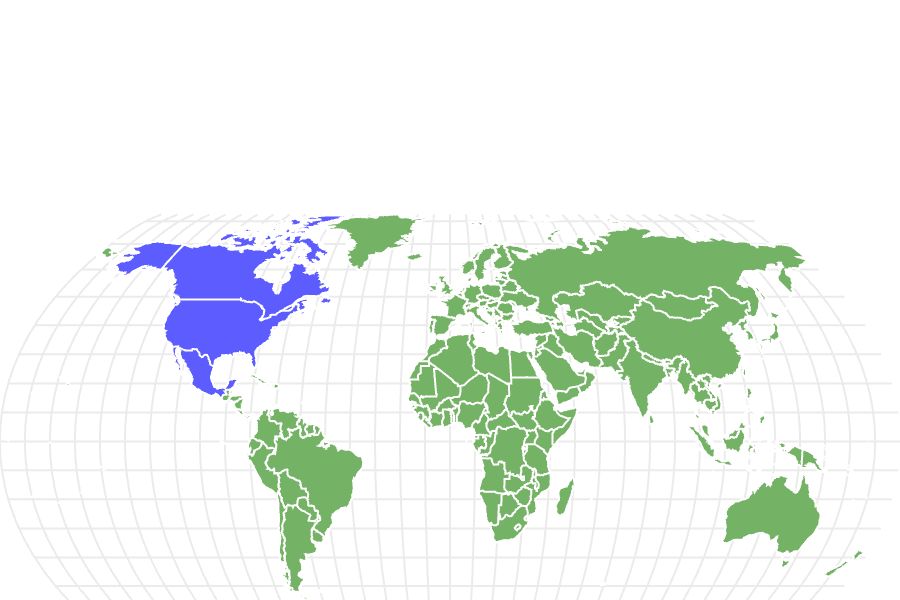

- North America

- Average Clutch Size

- 8

- Nesting Location

- On water

- Age of Molting

- 2 weeks

- Migratory

- 1

View all of the Canvasback images!

The canvasback is a species of duck found across North America, from Alaska to Mexico. Certain parts of its body, like its belly and back, are white with fine, wavy lines. This is what led to the name “canvasback”. It has an easily recognizable wedge-shaped head with a sloping bill. One of their favorite foods is wild celery.

Canvasback Amazing Facts

- Different ducks, including other canvasback females, will lay their eggs in a canvasback’s nest.

- Their nests can float on water.

- Canvasbacks get their scientific name from one of their favorite foods, a type of wild celery.

Where To Find Canvasback

The canvasback can be found only in North America. They’re a highly migratory species, with only two small year-round populations. One is located on the border between the United States and Canada in Washington, and the other is found in Colorado.

Outside of their summer breeding season, the canvasback can be found in much of the United States and Mexico. As they migrate, populations become denser along the eastern coast of the United States and in the Pacific Northwest. During the spring and summer when this species of duck begins to breed, it can be found mostly only in the western region of Canada and Alaska. Populations can also be found spread through the midwestern region of the United States, in states including Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota.

In their breeding areas, canvasback ducks can be found in deep-water habitats. This includes marshes, bays, and ponds. As they move south during the colder months, however, they’re more common in deep lakes and along the coast.

Nests

The nest of the canvasback is typically built on the water. However, it can sometimes be built on the land as well, though not as frequently. Females will choose the nesting spot. They prefer areas in shallow wetlands and waters, with high amounts of aquatic vegetation. This includes cattails, reeds, rushes, and sedges, which can easily be woven and utilized in nest building.

These aquatic plants are used to create a dense platform. Females will take these plants and weave them together. Then, the platform is attached to still-rooted plants so that it floats without floating away. Occasionally, these stalks also create an overhead canopy above the platform.

Once the eggs are laid and incubation begins, the nest will continue to change. For the first ten days, the female will continue to add materials to the nest, such as down feathers.

Canvasback Scientific name

The canvasback has the scientific name of Aythya valisineria. The species’ name comes from wild celery (Vallisneria americana), which is a favorite food of the canvasback. It belongs to the Anatidae family in the class of Aves.

Canvasback Size, Appearance, & Behavior

With their white markings, black chests, and brown heads, canvasbacks are a striking and unmistakable duck.

©Ray Hennessy/Shutterstock.com

Canvasbacks are named for the white markings on their backs and wings. They have black chests and tails, with brown heads. These black markings are paler on female canvasbacks. Males have bright red eyes, while females have black, shiny eyes. Canvasbacks grow to be between 18.9 inches and 22.1 inches long. Their wingspan can be nearly double this size, ranging from 31 inches to 35 inches. As adults, they weigh 30 to 50 ounces.

Canvasback ducks rarely go onshore. Instead, as a species of diving duck, they spend their lives on the water. They sleep while floating, with their bill tucked under their arm, and when it comes time to build a nest, they do it on platforms made of woven aquatic plants.

This is a highly social species of duck. They can gather in groups of thousands to tens of thousands. However, as winter approaches and food becomes more scarce, they can become less tolerable to social situations, defending areas with food from being foraged by other individuals. During breeding season, males become more aggressive as they begin to look for mates.

Migration Pattern and Timing

During the non-breeding season during the winter months, the canvasback can be found in much of southern North America. They live in most of Mexico, and throughout the midwestern region of the United States. In the States, they can be found as far north as Washington state and the New England region during the winter. There are very few year-round populations, and they are almost exclusively in the United States.

During the early stages of migration during the spring, groups of canvasbacks will form in certain areas, specifically in New England and the Pacific Northwest of the United States. As they migrate during breeding season, they’ll move into Canada and the northernmost areas of the Midwest.

Canvasback Diet

The canvasback is an omnivore. This means that it eats both animal matter and plant matter, with a widely diverse diet ranging from seeds to mussels.

During the breeding season, they can be seen eating plants and animals. However, as they migrate and settle in the south for the winter, such a diet is less common. Instead, the canvasback then eats primarily plants, specifically the rhizomes and tubers of the aquatic plants in their habitats.

As a species of diving duck, the canvasback acquires its food by diving deep into the water. They can dive straight down to reach depths of around 7 feet. Once underwater, they’re able to use their bill to pluck plants and mussels from the grown. They may also take food from the surface, such as insects.

What Does the Canvasback Eat?

The bulk of the canvasback’s diet is made up of plant materials, including leaves, roots, and seeds. The most popular plants for the canvasback are wild celery, pondweeds, grasses, and sedges.

However, as omnivores, they also eat other animals. This includes mussels, snails, and insections such as nymphs and larvae of dragonflies, mayflies, and midges.

Canvasback Predators and Threats

As with all aquatic species, canvasbacks are susceptible to threats such as loss of habitat and pollution of the waterways. However, they also face predation, especially on their nests.

When female canvasbacks are on their nest and notice a predator, they prioritize protecting their eggs. As a result, they will swim away from their nest to lure the predator’s attention elsewhere. Once the eggs hatch and the young are able to interact with their environments, it becomes easier to keep them safe from predators. When a threat is noticed, the mother can raise a warning call. This alerts the young and tells them to swim in the thick plant life around their nest.

Predation is most common during the breeding season. This is because outside of breeding, canvasbacks live in large groups. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the canvasback is a species of least concern.

What Eats Canvasbacks?

There are several predators that prey upon the canvasback. Most predation is directed towards young or eggs. The main predators here include raccoons, skunks, foxes, minks, and ermines. Both young and adults are preyed on by raptors and large birds. Adult canvasbacks are also eaten by coyotes and snapping turtles.

Canvasback Reproduction, Babies, and Lifespan

Female canvasbacks are known as hens, while males are known as drakes. Mating pairs of canvasbacks are formed during their migration in the spring. Once they reach the northern region of their range, they settle into their pairs to build their nests in the wetlands.

In the middle of incubation, females and males part ways. The female canvasback will stay at the nest, and continue to incubate the eggs. Males, however, will move into western and central Canada to begin their molting period. Once molting is complete and the young canvasback hatchlings are more independent, both males and females will migrate south for the coming winter season.

Canvasbacks have one brood per year. Their clutch can contain anywhere from 5 to 11 eggs, each of which is greenish in color and less than 3 inches long. Hatchlings emerge from their eggs with a down coating. Since hatching occurs soon before the migration back south, they are prepared to leave the nest soon after emerging from their eggs.

Canvasback Population

Since the 1950s, the canvasback population has been highly susceptible to fluctuations. In the 1980s, they were considered to be a species of concern. However, the number of canvasbacks has greatly increased in the past few decades. As of 2017, it was estimated that there were around 700,000 canvasbacks in the United States.

Related Animals…

View all 235 animals that start with CCanvasback FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Does the canvasback migrate?

Canvasbacks are highly migratory birds that migrate each spring and fall.

How many eggs does the canvasback lay?

Canvasbacks lay between 5 and 11 eggs in each clutch.

How fast do canvasbacks fly?

Canvasbacks average around 50 miles per hour in flight, but they can reach speeds of 70 miles per hour.

What is the canvasback's wingspan?

Their wingspan ranges from 31 inches to 35 inches.

When do canvasbacks leave the nest?

Canvasbacks leave the nest within a few weeks of hatching.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- 02/15/2023, Available here: https://academic.oup.com/auk/article-abstract/118/4/1008/5562275