Gypsy Moth

Lymantria dispar

One of the most invasive species in the world

Advertisement

Gypsy Moth Scientific Classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Arthropoda

- Class

- Insecta

- Order

- Lepidoptera

- Family

- Erebidae

- Genus

- Lymantria

- Scientific Name

- Lymantria dispar

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Gypsy Moth Conservation Status

Gypsy Moth Facts

- Prey

- Foliage from trees and shrubbery

- Main Prey

- Hardwood tree foliage

- Name Of Young

- Larvae (caterpillars)

- Group Behavior

- Solitary

- Fun Fact

- One of the most invasive species in the world

- Estimated Population Size

- Hundreds of millions or billions

- Biggest Threat

- Predators

- Most Distinctive Feature

- Prey on 500 different types of plants

- Distinctive Feature

- Caterpillars feature small, uricating hairs

- Other Name(s)

- Spongy moth

- Wingspan

- 1.5-2.0 inches

- Incubation Period

- 10 - 14 days

- Average Spawn Size

- 600

- Habitat

- Forests

- Predators

- Birds

- Diet

- Herbivore

- Lifestyle

- Crepuscular

- Solitary

- Favorite Food

- Oak foliage

- Common Name

- Gypsy moth

- Number Of Species

- 1

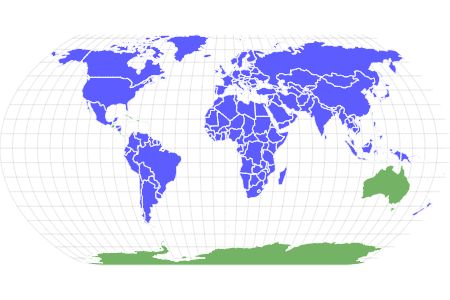

- Location

- Worldwide excluding Australia and Antarctica

Gypsy Moth Physical Characteristics

- Color

- Brown

- Grey

- Yellow

- Red

- Blue

- Black

- White

- Tan

- Cream

- Light Grey

- Dark Grey

- Black-Brown

- Skin Type

- Hairs

- Lifespan

- 1 year

- Length

- 0.25-2.5 inches

- Age of Sexual Maturity

- After hatching from pupal stage

- Venomous

- No

- Aggression

- Low

View all of the Gypsy Moth images!

Summary

One of the most invasive species in the world, the gypsy moth is a member of the moth family Erebidae. While originally native to isolated regions of Europe and Asia, you can now find gypsy moths throughout the world.Their larvae feed on a wide variety of coniferous and deciduous trees, in some instances, severely damage a region’s biodiversity. Every year, these moths destroy millions of acres of forests and cause billions of dollars in damages.

Gypsy Moth Facts

- The gypsy moth was first introduced in the United States in 1868 to breed a sturdier species of silk-spinning caterpillar.

- Gypsy moth larvae possess hairs with small air pockets that allow them to float on the breeze over great distances.

- Although they prefer oaks, gypsy moths prey on over 500 different tree and shrub species.

- Female gypsy moths attach egg masses to trees and shrubs that can contain up to 600 eggs each.

- Numerous methods have been employed to control gypsy moth populations, including parasitic and predatory insects, insecticides, and bacterial, fungal, and viral diseases.

Gypsy Moth Species, Types, and Scientific Name

Also known as the spongy moth, the gypsy moth belongs to the family Erebidae. Its subfamily, Lymantriinae, often goes by the name tussock moths due to the tussock-like hairs on the caterpillars. While the term gypsy refers to a sole species, Lymantria dispar, scientists recognize several different subspecies. Its generic name, Lymantria, derives from the Latin word for destroyer, while its species name translates as to separate in Latin. Taken together, these names reference both the gypsy moth’s destructive behavior and the fact that the males and females display traits of sexual dimorphism. In recent years, the name spongy moth has begun to replace gypsy moth, which can be used as a pejorative toward Romani people.

The recognized subspecies of gypsy moth include:

- Lymantria dispar dispar – European gypsy moth

- Lymantria dispar asiatica – Asian gypsy moth

- Lymantria dispar japonica – Japanese gypsy moth

Appearance: How to Identify Gypsy Moths

Over the course of their lives gypsy moths vary wildly in appearance. They look dark brown or black at birth and measure approximately 0.63 centimeters (0.25 inches) long. They feature long brown hairs and five pairs of blue dots followed by six pairs of red dots along the back. The head appears black and tan, and a thin yellow line runs the length of their body. By the time the caterpillars fully mature, they measure approximately 6.35 centimeters (2.5 inches) long.

Gypsy moth caterpillars feature long brown hairs and five pairs of blue dots followed by six pairs of red dots along the back

©iStock.com/grannyogrimm

Next comes the pupal stage, which lasts approximately 10 to 14 days. Unlike some caterpillars, these moths do not spin a silk cocoon, although the pupae may attach themselves to a nearby substrate using several strands of silk. The pupae appear dark brown and shell-like and measure approximately five centimeters (two inches) long. On average, female pupae measure slightly larger than males.

Male gypsy moths emerge before females. They look predominantly gray-brown and sport feathery antennae. The males measure slightly smaller than females, with an average wingspan of approximately 3.8 centimeters (1.5 inches). Females have a wingspan of approximately five centimeters (two inches) long and lack the feathery antennae of the males. They possess creamish-white colored wings and a tan body. Unlike the males, female cannot fly. Both males and females have an inverted V-shape on each wing pointing toward a dot.

Habitat: Where to Find Gypsy Moths

The native range of gypsy moths varies depending on the subspecies. For example, L. d. dispar originally hails from temperate forests in western Europe as well as parts of Eurasia and North Africa. Meanwhile, L. d. asiatica is native to Eastern Asia, while L. d. japonica originates from the island of Japan. The spread to North America began in 1868 when a French scientist named Etienne Leopold Trouvelot imported some gypsy moths in the hopes of breeding them with native moths to make a hardier hybrid silk-spin caterpillar species. While mainly confined to the eastern United States, you can now find gypsy moths throughout much of North and South America. Today, you can find gypsy moths on every continent except for Australia and Antarctica.

Female gypsy moths lay their egg masses on tree trunks or sturdy shrubs. They prefer to lay their eggs on hardwood trees but will take advantage of whatever they can find, including rocks, foliage, and buildings. Eggs overwinter in the egg masses until they hatch in the spring. The newly hatched caterpillars then disperse to nearby foliage. If they can’t find enough food for their development, they will balloon to new hosts. They can travel miles away from their original birth site until they find a suitable spot to settle down.

Diet: What Do Gypsy Moths Eat?

Gypsy moths only eat during the larval (caterpillar) stage of their life cycle. Shortly after hatching, the caterpillars set out in search of foliage. If they cannot find enough suitable food, they will float on silk threads through the air in a method known as “ballooning” until they find food. Younger caterpillars tend to feed during the day, while older caterpillars typically feed at night. Nighttime feeding helps the caterpillars avoid the heat of the day and predators such as birds. However, older caterpillars may feed in high-density populations day and night. The caterpillars eat for 6 to 7 weeks, with their appetite gradually increasing as they age and grow.

Gypsy moths feed on the foliage of over 500 known species of trees and shrubs. While they prefer hardwood trees such as oak, they will also readily eat the foliage of conifers. Plants commonly eaten by gypsy moths include aspen, alder, birch, poplar, hawthorn, cottonwood, pine, spruce, and willow.

Prevention: How to Get Rid of Gypsy Moths

Over the years, numerous biological pest control measures have been deployed to curtail the spread of gypsy moths. One of the first methods entailed the introduction of parasitic and predatory insects such as deer mice, tachinid flies, and braconid wasps. While some of these species can help reduce gypsy moth populations, others play little role in managing population dynamics. Moreover, some species do more harm than good by decimating native moth populations while leaving gypsy moth populations relatively unchanged. At the beginning of the 19th century, people started to use powerful pesticides such as DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) to eliminate gypsy moths. Although they successfully eliminated the moths, some of these chemicals also negatively impacted local environments by harming honeybees, eagles, and other fauna. While DDT is now banned, chemical pesticides such as Foray, Orthene, and Sevin are widely available alternatives.

Today, commonly employed methods to remove these pests include targeted microbial pathogens, viruses, and funguses. For example, Lymantria dispar multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus (LdmNPV) targets gypsy moth caterpillars and causes them to disintegrate. Similarly, the fungus Entomophaga maimaiga causes high levels of infection amongst gypsy moths, particularly those living in high-density populations. When used strategically, mating disruption can also effectively curtail infestations. Mating disruption involves the constant release of species sex pheromones. These pheromones trick the males into following false trails, thereby reducing the number of mating encounters between moths. Finally, the active removal of egg masses and the physical destruction of caterpillars also helps to reduce gypsy moth populations, although these methods are time-consuming and difficult to enact en masse.

Related Animals

View all 170 animals that start with GGypsy Moth FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Are gypsy moths dangerous?

While gypsy moths are incredibly harmful to trees and plants, they pose no danger to humans.

How many legs do gypsy moths have?

Gypsy moths have six segmented legs as adults.

How do you identify gypsy moths?

As caterpillars, gypsy moths look dark brown and feature five pairs of blue dots and six pairs of red dots along the back. Male adults look dark grey and have feathery antennae, while adult females have creamish-white wings and tan bodies.

How do you get rid of gypsy moths?

Many methods exist to manage gypsy moth populations. Some of the most effective methods include removing egg masses, using targeted viruses, bacteria, and funguses, maintaining trees’ health, and using sex pheromones to disrupt mating.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- psu.edu, Available here: https://extension.psu.edu/gypsy-moths

- Illinois.edu, Available here: https://web.extension.illinois.edu/gypsymoth/biology.cfm

- in.gov, Available here: https://www.in.gov/dnr/entomology/regulatory-information/gypsy-moth/

- aphis.usda, Available here: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/planthealth/plant-pest-and-disease-programs/pests-and-diseases/gypsy-moth/ct_gypsy_moth

- si.edu, Available here: https://www.si.edu/spotlight/buginfo/gypsy-moths

- canada.ca, Available here: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/pest-control-tips/gypsy-moths.html