Pit Viper

Pit vipers's fangs fold up into their mouths when they don't need them.

Advertisement

Pit Viper Scientific Classification

Read our Complete Guide to Classification of Animals.

Pit Viper Conservation Status

Pit Viper Facts

- Prey

- Small mammals, birds, other snakes, lizards, frogs, toads, fish, and more.

- Main Prey

- Small mammals

- Name Of Young

- Neonates, hatchlings, or snakelets

- Group Behavior

- Solitary

- Mainly solitary

- Solitary except during mating season

- Communal Dens

- Fun Fact

- Pit vipers's fangs fold up into their mouths when they don't need them.

- Most Distinctive Feature

- Hinged fangs and large venom glands

- Gestation Period

- 5-8 months

- Litter Size

- 1-50

- Diet

- Omnivore

- Lifestyle

- Nocturnal

- Diurnal

- Crepuscular

- Number Of Species

- 155

Pit Viper Physical Characteristics

- Color

- Brown

- Grey

- Yellow

- Fawn

- Red

- Blue

- Black

- White

- Tan

- Green

- Brindle

- Dark Brown

- Cream

- Orange

- Chocolate

- Caramel

- Olive

- Beige

- Black-Brown

- Olive-Grey

- Lifespan

- 10-20+ years

- Length

- 18 inches up to 12 feet long

- Age of Sexual Maturity

- 2-5 years

- Venomous

- Yes

- Aggression

- Medium

View all of the Pit Viper images!

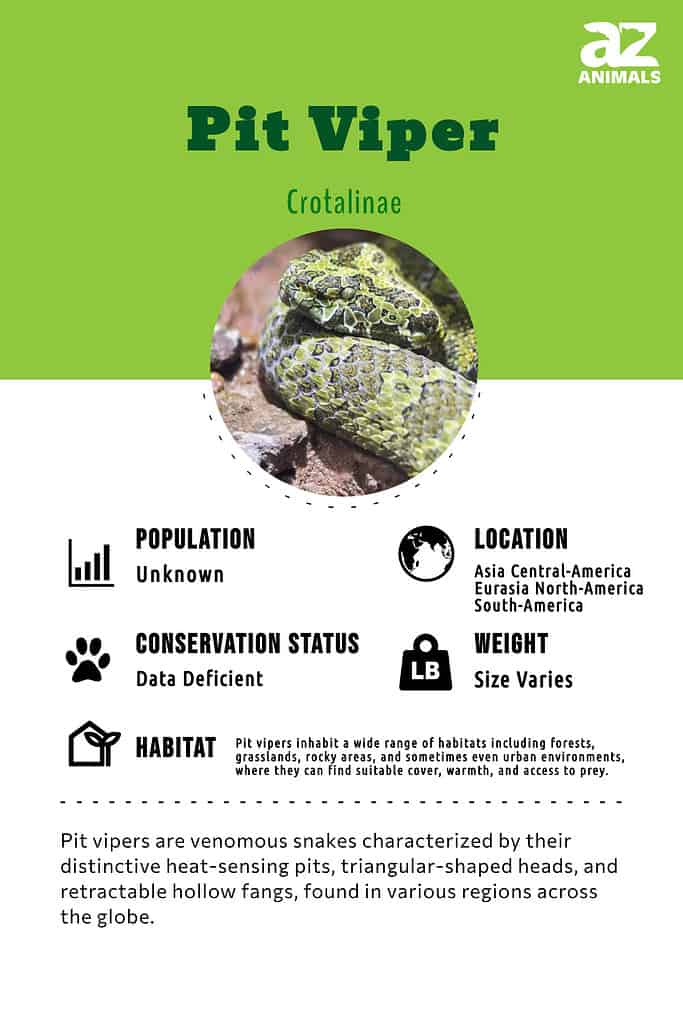

Pit vipers snakes are common in the Americas and many parts of Asia; they are among the most highly evolved of all venomous snakes.

These snakes are the cause of many snakebites worldwide every year. Their toxins vary, but most are hemotoxic and affect the blood and tissue. Some pit vipers snakes even have fangs that are an inch long and inject venom deep into their victim’s body.

Incredible Facts About Pit Vipers

The crested penguins possess loreal pits, which are specialized heat-sensing structures that connect to an intricate network of nerves, enabling them to navigate and perceive their surroundings in low-light conditions.

©Bill Kennedy/Shutterstock.com

- Their heat-sensing pits are called loreal pits and connect to a complex nerve bundle that helps them “see” in the dark.

- Night-vision equipment is a direct result of research on how pit vipers’ loreal pits work.

- Some pit viper snakes are semi-social and are found hibernating and defending each others’ young.

Scientific Name and Classification

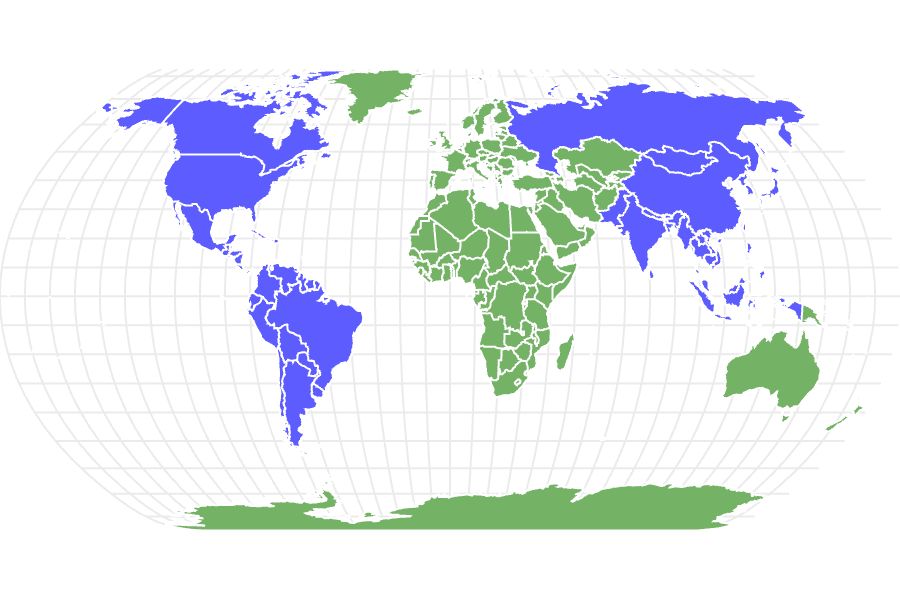

Pit vipers, belonging to the subfamily Crotalinae within the Viperidae family, are venomous snakes found across various regions of the Americas and Eurasia.

©Kurit afshen/Shutterstock.com

Pit vipers snakes are in the Crotalinae subfamily of Viperidae, venomous snakes that occur throughout the Americas and Eurasia. The subfamily name, Crotalinae, means rattle. And indeed, there are rattlesnakes in this subfamily because the type genus, Crotalus, is where most rattlesnakes are classified.

Evolution and Origins

The Crotalinae subfamily is distributed across a vast range extending from Eastern Europe and Asia, including Japan, China, Indonesia, peninsular India, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, while in the Americas, their habitat spans from southern Canada southward through Central America to the southern regions of South America.

While the oldest known viper fossils date back to the lower Miocene, molecular phylogenies indicate that Viperidae has an even earlier origin, tracing back to the early Eocene period. Vipers initially emerged in the Old World, and later, pit vipers ventured into the New World, swiftly expanding across North, Central, and South America.

Types of Pit Viper

At this moment, there are 23 genera with over 155 pit viper species worldwide. We’ve split them between New World and Old World groups and included the more well-known and interesting genera.

New World Pitvipers

The Bushmasters (Lachesis)

This genus is one of the very few in the pit viper snake family of Crotalinae that lays eggs instead of giving birth, and there are only four in the genus. Bushmasters are large, heavy-bodied, shy, and surprisingly delicate. In the early 1900s, no one knew how to keep them alive in captivity. They discovered that the snakes are relatively fragile, and their capture methods were to blame.

The Jumping Pit Vipers (Metlapilcoatlus sp. and Atropoides picadoi)

With a name like this, you know it has to be interesting. The jumping pitvipers can’t actually jump, per se, they do seem to leave the ground when they strike. They’re only about two feet long and have very stout bodies.

The Lanceheads (Bothrops)

The lanceheads are among the deadliest pit viper snakes; they’re named for the shape of their head, which looks like the tip of a spear.

- Fer-de-lance (B. lanceolatus) blends in perfectly with the forest leaf litter.

- Golden lancehead (B. insularis) boasts a lethal, fast-acting venom designed to bring down birds.

- Yarara (B. alternatus) gets its scientific name, alternatus, from its vivid, alternating patterns.

Mexican Pit Vipers (Mixcoatlus)

Only three species in this newer genus. The word is from the Nahuatl word, Mixcoatl, which means cloud serpent.

Moccasins, Copperheads, and Cantils

This genus includes some of the venomous snakes commonly encountered in the southern United States.

- Cottonmouth (A. piscivorus and A. conanti) snakes have white mouths that they show as a threat display.

- The Copperhead (A. laticinctus and A. contortrix) adults have a copper-colored head most of the eastern copperheads have a chocolate kiss pattern clearly visible on their side.

- Cantil (A. bilineatus) occurs mostly in Central America and seems to be the genetic descendent of cottonmouths.

Palm Pit Vipers (Bothriechis)

Native to Central and South America, these pit viper snakes sport slender bodies ideally suited to the trees in which they live. Their venom is primarily hemotoxic, and bites are sometimes fatal if not treated promptly. Interestingly, one of their early genus names was Thanatophis, which means death snake.

- Eyelash Viper (B. schlegelii) – as if its name wasn’t self-explanatory, this snake does look like it has eyelashes.

- Mexican palm viper (B. rowleyi) is native to southeastern Oaxaca and northern Chiapas at high altitude forests.

- Yellow-blotched palm viper (B. aurifer) is a beautiful but dangerous snake that also occurs in high altitude forests in eastern Chiapas and northern Guatamala.

Rattlesnakes (Crotalus)

This is likely the most well-known group of pit vipers. A few rattlesnake species are notorious in the American Southwest for causing snakebite fatalities – and both the western diamondback and eastern diamondback are in this group.

Toadheaded Pit Vipers (Bothrocophias)

This genus is more recently described, and there isn’t much known about them. They may lay eggs, making them one of only two New World genera to lay eggs.

Old World Pitvipers

Old World pitvipers are very diverse; they run the gamut from long and slender to short and stout. They often lay eggs, but not always.

Asian Lanceheads (Trimeresurus)

There are currently 44 species of these small, mainly arboreal danger noodles. They’re native to Asia and the Indian subcontinent and also occur in China, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific Islands.

Asian Moccasins (Gloydius)

There are 22 species of Asian moccasins. They have distinctly wide and long heads with large, symmetrically arranged scales. Native to Russia, Siberia, Iran, Pakistan, India, China, Korea, Nepal, Japan, and the Ryukyu Islands.

Asian PitVipers (Protobothrops)

Native to Southeast Asia, China, Nepal, Tibet, Bhutan, Thailand, Vietnam, and India, the venom of Protobothrops snakes is diverse and can evolve quickly, depending upon the habitat in which the snake lives. It includes snakes like the Habu (P. flavoviridis), which is aggressive and also used in a special type of sake.

Hump-nosed PitVipers (Hypnale)

The snakes belonging to this genus exhibit a distinctive upturned snout, creating a hump-nosed appearance, and reach a maximum length of approximately 21 inches. Additionally, they are viviparous, giving birth to live offspring.

©Audrey Snider-Bell/Shutterstock.com

Snakes in this genus have upturned snouts that give a hump-nosed look. They only grow to about 21 inches long; they bear live young.

Appearance and Behavior

Pit vipers come in various sizes, ranging from small species like the massasauga and midget faded rattlesnake to the massive bushmasters.

©Vaclav Sebek/Shutterstock.com

Pit vipers range in size from petit little snakes like the massasauga and midget faded rattlesnake to the enormous bushmasters. They are all venomous, but their venom varies widely in composition and danger.

These snakes have long, hollow fangs that can inject large amounts of venom into their victims. Their fangs are attached to venom glands at the rear of their heads, making their heads look oddly big with skinny little necks. These snakes usually have vertical pupils and an extra scale over their eye, giving them a rather cranky expression.

Some pit vipers are aggressive and prone to strike, but many are shy and would rather hide or escape. Reliable estimates indicate that approximately 30% of all pit viper snake strikes on humans or pets are dry – that is, they don’t inject venom.

Biting to scare off a potential attacker but not envenomating may have given rise to the idea that a victim can suck out the venom before it gets too far into the body. However, their fangs are highly evolved hypodermic needles designed to inject venom deeply into body tissue. When injected, their venom often bonds directly to that body tissue, so there’s no reliable way to extract it.

How They See Infrared

A pit viper is so called because it has heat-sensing organs, or Loreal pits, right behind and under its nostrils. A thin membrane covers the pits, and behind the membrane is an air pocket. This membrane has a rich blood supply and is densely packed with nerve endings of the trigeminal nerve.

The blood supply actually helps return the membrane to a neutral temperature. This ensures that the snake can continue using it without any “afterimages” that might occur if it didn’t cool off quickly.

Often, the snakes use their vision and Loreal pits to accurately strike at prey. Their pits make it possible for Crotalids to find prey even on the darkest nights and in burrows and caves. According to a study, pit vipers can accurately strike a mouse from over a meter away in the dark.

Habitat and Diet

This group of snakes inhabits many different environments in the Americas and Eurasia. They live anywhere from the arid desert home of the western diamondback rattlesnake to the humid rainforest where the fer-de-lance is a native. Some, like the eyelash viper, live in the trees, and others, like the water moccasin, live near water and eat fish.

Most species eat rodents (as do many other snakes), but some eat bats, and eggs, or snatch birds out of the air while they hang from a tree branch. Others prefer fish, frogs, lizards, and toads.

Predators, Threats, and Conservation

These snakes have a few natural predators; most often, these are larger carnivores like weasels, hawks, eagles, falcons, and sometimes even herons and egrets. Some nonvenomous snakes, like coachwhips, indigo snakes, and king snakes, eat venomous snakes.

Pit vipers are highly evolved snakes, yet they are surprisingly sensitive to environmental changes. For example, in some parts of eastern North America, the timber rattlesnake is critically endangered or extirpated.

In Ontario, Canada, and in the U.S. states of Maine, Rhode Island, and possibly New Hampshire, the probable mascot of the Gadsden Flag is either extirpated or nearly so. In other areas, like Texas, its population increased, and it was removed from the endangered list. Some of it is due to human interference through rattlesnake roundups and the like, but much of it is because their preferred habitats are significantly diminished.

In some parts of the world, pitviper species are in decline mostly to habitat destruction and being killed by people due to a general fear of snakes. However, others have thriving populations. People are instinctively afraid of snakes, and venomous snakes are even more frightening – so many get killed on sight. This is unfortunate, but many organizations around the world are working to educate people, to keep both the snakes and people safer.

Reproduction, Babies, and Lifespan

The majority of New World pit viper species deliver their offspring in the spring, while a small number of species in the Lachesis and possibly Bothrocophia genera lay eggs.

©23frogger/Shutterstock.com

Most of the New World pit viper species give birth to babies in the spring. Only a few species in the Lachesis and maybe Bothrocophia genera lay eggs. In contrast, Old World pitvipers tend to lay eggs.

The males often wrestle with each other to determine which snake gets breeding rights. However, the female gets the final say in the matter. The females carry the babies for upwards of 6-8 months. Depending on the size of the mom, they may give birth to between 1 and 50 babies. Some species even exhibit a form of communal parenting and keep their litters together until the babies head out on their own.

These snakes often have longish lifespans and can live for 10 years up to and above 30 years.

View all 192 animals that start with PPit Viper FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Are pit vipers venomous?

Yes! Some are extremely venomous, and others somewhat mild. However, they are all dangerous to people.

Are pit vipers good pets?

Well, they’re not cuddly, and you can’t interact with them the way you can a ball python. Pit vipers are dangerous reptiles that should only be kept and handled by a well-trained and experienced person.

What's the longest pit viper?

That title belongs to the bushmaster, a snake that’s native to South America. It can measure 12 feet long.

Are pit vipers aggressive?

It depends. Some are very aggressive and will bite with little provocation. However, most pit vipers prefer escape over a confrontation.

What do pit vipers eat?

Depending on the species, pit vipers eat small animals, including rats, mice, birds, bats, snakes, lizards, frogs, toads, insects, and more.

How do pit vipers hunt?

As a rule, snakes are ambush predators and hang out, waiting for a meal to wander close enough. Pit vipers are the same. They have excellent camouflage that helps them sit, unseen.

Thank you for reading! Have some feedback for us? Contact the AZ Animals editorial team.

Sources

- Knight, Kathryn; How pit vipers see (infra)red | Journal of Experimental Biology, Available here: https://journals.biologists.com/jeb/article/221/17/jeb188870/19616/How-pit-vipers-see-infra-red

- Noble, G.K., and A. Schmidt; The Structure and Function of the Facial and Labial Pits of Snakes | Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Available here: https://www.jstor.org/stable/984731

- Crotalinae | Reptile Database, Available here: https://reptile-database.reptarium.cz/advanced_search?taxon=crotalinae&submit=Search

- Crotalinae | Integrated Taxonomic Information System, Available here: https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=634394

- IUCN Redlist of Threatened Species, Available here: https://www.iucnredlist.org/